The U.S. Army’s Bird of Paradise arriving at Wheeler Field on the Hawaiian island of O‘ahu on June 29, 1927, completing the first nonstop flight across half of the Pacific. Courtesy of the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force.

Approximately 20 million airline passengers traveled through Hawaiian airports last year. That might seem like a lot of people on a couple of small Pacific islands, but Hawai‘i hardly broke a sweat handling so many fliers.

Ever since the late 1950s, when the advent of the jet engine revolutionized commercial air travel, Hawai‘i has enjoyed, or some would say endured, an unceasing tourist boom. Since that time the state has become adept at handling an overwhelming number of passengers traveling to and from Asia and the mainland United States.

Yet this impressive tally of travelers, as well as the availability of so many direct and inexpensive flights to the Hawaiian Islands, obscures a foundational truth about air travel to Hawai‘i: Less than a century ago, it was a near-miracle for anyone to arrive to the Paradise of the Pacific by airplane.

In fact, 17 of the 25 aviators who attempted the first transpacific flights failed to land in Hawai‘i.

Despite their high rate of failure, these aviators’ efforts during the summers of 1925 and 1927 were instructive and inspiring. It took tremendous courage to wing across the water for more than 24 hours from California, traveling across half an ocean in a fragile, primitive flying machine made mostly of wood and fabric. These early American aviators were incredibly determined and industrious, as well as dead set on establishing an air link between Hawaiian shores and the mainland, no matter the danger of crossing 2,400 miles of open water.

As the young civilian air navigator Emory Bronte exclaimed in 1927, “As far as I’m concerned, it’s heaven, hell, or Honolulu for me—and I know it’ll be Honolulu!”

These first flight attempts to Hawai‘i occurred during the golden age of aviation, the two decades between the World Wars when the airplane matured from a curiosity to a useful, semi-reliable, and absolutely revolutionary mode of travel. Airplanes of this era evolved from biplane designs to monoplanes, and used more powerful and efficient engines. By the mid-1920s, airplanes regularly flew between cities, above mountains, and over lakes, jungles, and deserts. Aviators, too, were performing amazing feats, pulling off airplane stunts for movie cameras and air show crowds, landing on ships, and consistently shattering speed and altitude records.

Yet for all this progress, by 1925 there was one glaring omission on the list of aviation accomplishments: No one was making nonstop flights across oceans. (The exception was one flight in 1919 between Newfoundland and Ireland that ended in a crash landing, but that’s a different story.)

To remedy this shortage of transoceanic flight—and to establish an air route to military facilities at Hawai‘i’s Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy organized its own pioneering, transpacific, and nonstop West Coast-Hawai‘i Flight. On the afternoon of August 31, 1925, two Navy flying boats (a type of seaplane that combined a boat hull with wings) took off from the northern arm of San Francisco Bay, beginning an anticipated 26-hour flight to Pearl Harbor. Tens of thousands of people lined the bay and stood on San Francisco rooftops to watch the flying boats, heavily laden with fuel for the long flight, slowly lift from the bay, fly past Alcatraz, and pass through the Golden Gate (which had yet to be bridged).

“Running parallel with the shore for a mile or more,” wrote San Francisco Mayor James Rolph, “they rose as gracefully as two birds.”

Flying out past the Farallon Islands and across open ocean, the flying boats tracked a path toward Maui, the nautical midpoint of the Hawaiian Islands. Aiming for Maui was important. While lots of things could go wrong on the 26-hour flight, from mechanical failure to pilot fatigue to bad weather, the biggest worry was navigational error. Should the flying boats’ route be off more than three degrees when leaving San Francisco, its crews would not even spy the Hawaiian Islands and could become hopelessly lost above the world’s largest ocean.

To help ensure safe passage, the Navy placed ships every 200 miles along the flight path, providing visual markers for the aircraft as well as assistance should the flying boats need to refuel or make repairs. This guard line of vessels proved its worth when one of the two flying boats was forced down atop the waves because of a broken oil line and needed a tow back to San Francisco.

The oil line mishap left just one Navy aircraft remaining in the air—flying boat PN-9 No. 1. Operated by Commander John Rodgers and a crew of four, this flying boat powered on through the night, keeping course by use of a variety of navigational tactics, including dead reckoning, radio communication, celestial navigation, and the consistent sighting of the line of Navy guard vessels. But while the flying boat was on course, it was not on time. The aircraft had battled an unrelenting headwind from the start.

As gas ran low and the headwind persisted, Rodgers grudgingly conceded he could not make a nonstop flight and made plans to rendezvous with a refueling ship about 500 miles from Hawaii. But when he alighted hours later atop the water in a bad rainstorm, a radio mix-up left him and his crew desperately alone, out of sight of any nearby Navy vessels.

As hours and then days passed without rescue, the crew of the floating flying boat realized the Navy might never find them, especially since their radio transmitter was inoperable, leaving them incommunicado. So, in a resourceful moment, the Navy men ripped fabric from the flying boat and strung up the cloth between the upper and lower wings of the floating aircraft. If they couldn’t fly all the way to Hawai‘i, they decided, they’d sail there. And so they did for ten days, all the while slowly starving and suffering from thirst as sharks and barracuda trailed their clumsy and slow-moving, makeshift sailboat.

Finally, as they sailed through the channel between the islands of O‘ahu and Kaua‘i, a Navy submarine spotted the missing Navy craft and towed them into a harbor at Kaua‘i. The world rejoiced over the rescue and the crew’s amazing flight and voyage. But still it remained for someone to fly nonstop across the Pacific to Hawai‘i.

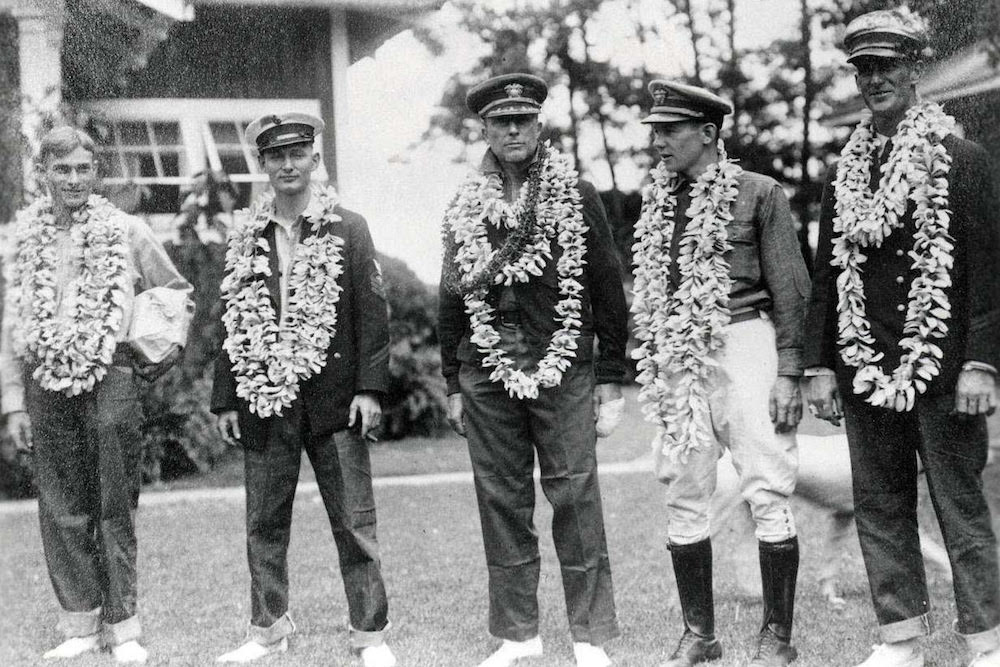

The U.S. Navy crew of PN-9 No. 1, rested and bedecked in leis on Kaua‘i in September 1925 after 10 days lost at sea. Courtesy of the Naval History and Heritage Command.

Two years later, aviators were again ready to tackle the oceans. In May 1927 the young American airmail pilot Charles Lindbergh shocked the world by flying alone and nonstop across the Atlantic, from New York to Paris. Overnight, Lindbergh became an international hero, a model of ambition and derring-do. Among those inspired by Lindbergh’s feat was James Dole, Hawai‘i’s pineapple baron.

Dole, eager to connect the islands to the wider world and expand the local economy, offered a $25,000 prize to the first aviators to duplicate Lindbergh’s flight and cross the Pacific to Hawai’i. When dozens of people responded enthusiastically to the offer, Dole had to amend his contest and establish a formal air race to Hawai‘i, with all aviators able to leave for the islands on a race day set at the end of the summer.

Meanwhile, other flyers chose to skip Dole’s contest and try for Hawai‘i even sooner.

The U.S. Army had been preparing for a transpacific flight since the beginning of 1927, hoping to finish the job started by the Navy. And when the Army Air Corps’ plans for the flight became public in the days after Lindbergh’s epic flight, the military picked up a civilian rival. By the end of June 1927, a month after Lindbergh’s flight, two planes sat at the start of the runway at the new Oakland Airport along San Francisco Bay: a trimotor Fokker C-2 designated by the Army as Bird of Paradise and a single-engine Travel Air 5000 named City of Oakland, which was to be piloted by civilian Ernie Smith. With tens of thousands of Bay area residents again watching the beginnings of transpacific flights, the planes took off on June 28, each aiming to be the first to fly to Hawai‘i.

Inside Bird of Paradise, Lieutenant Lester Maitland piloted the plane while Lieutenant Albert Hegenberger provided expert navigation. They made the flight across the Pacific with hardly a hiccup, arriving to a hero’s welcome on O‘ahu, where a healthy portion of Honolulu’s population stayed up through the night to welcome the aviators the morning of June 29.

City of Oakland’s flight, however, was short-lived, as a wind deflector broke off the aircraft just a few minutes after takeoff, requiring Smith to abort the flight and return to Oakland. Two weeks later, however, he was en route to O‘ahu once again, taking along a new navigator, Emory Bronte. They flew above fog the entire way, not seeing ocean until they sighted the Hawaiian Islands a full 24 hours after takeoff. But just as they spotted the islands, their gas began to give out, forcing the daring duo to make a crash landing in a thicket of thorn trees on Molokai. Smith and Bronte had both flown safely to Hawai‘i, but landed on the wrong island!

Despite Bird of Paradise and City of Oakland both making the Hawaiian Hop, James Dole insisted his contest would continue. So weeks later, on August 16, 1927, eight planes containing 16 pilots and navigators took off from Oakland in succession, about two minutes apart. Three other entrants in the race had died in crashes en route to the starting line.

The bad fortune continued during the race, as only four planes successfully flew away from the coast. The other flights were all foiled by mechanical problems or crashes during takeoff. And of the four planes that cruised out over the Pacific, only two finished the race, with Hollywood stunt flier Art Goebel and his navigator, Navy Lieutenant William V. Davis, capturing first prize in Woolaroc and barnstormer Martin Jensen and his navigator Paul Schluter finishing as runners-up in Aloha.

Gone missing over the Pacific was Golden Eagle, a speedy Lockheed plane sponsored by the Hearst newspaper chain, and Miss Doran, a biplane carrying a pilot, navigator, and one famous passenger: a 22-year-old schoolteacher from Michigan named Mildred Doran. Photos and interviews of the cute and sassy “Flying Schoolma’am” had been splashed across newspapers for weeks leading up to the race, endearing the young woman to Americans nationwide. “I’m really tickled to pieces to be here, and I haven’t the slightest misgivings about the coming jaunt to Hawai‘i,” Doran said before her disappearance. “I’ve always wanted to do something different and to be the first woman to do it.”

In the wake of so many deaths, the Dole Derby became known as the Disaster Derby. As an indication of the considerable danger still present in any ocean crossing, all those aviators who flew nonstop across the Atlantic and Pacific in the summer of 1927 packed up their planes and took steamships back home. No one wanted to push their luck by flying across so much water once again.

But progress would not wait forever. By the 1930s, Pan Am Clipper ships started regular service to Hawai‘i, only to be interrupted by World War II. In the late 1950s, the first passenger jets began landing in Honolulu, launching the modern age of air travel to the Paradise of the Pacific.

Nowadays, anyone with a few hundred dollars can fly comfortably and safely to Hawai‘i from California. Next time you do so, remember that the air route you’re traveling was pioneered by a few brave American men and women, some of whom gave their lives in the pursuit of new paths across the Pacific.

Send A Letter To the Editors