A Berkeley voter leaves City Hall after voting in the California primary election in June, 2018. Photo by Lorin Eleni Gill/Associated Press.

If we want our civic life to be more positive, we might need to vote in the negative.

That’s the compelling case that Sam Chang, a retired banker who lives in Taipei, was making as I rode BART with him between meetings with California election experts. Chang is the improbable leader of a global effort to establish what is called “the negative vote” or “the balanced ballot.” And he has started with concurrent ballot initiative campaigns to add the “negative vote” to the election system in Taiwan and the city charter in Berkeley.

In this transnational campaign, Chang, a mild-mannered 67-year-old who holds both Taiwanese and U.S. citizenship, is in the vanguard. California and its communities, who are famously open to new ideas advanced by initiative, are likely to become proving grounds for coordinated initiative campaigns that advance democratic reforms internationally. Over recent decades, direct democracy—which refers to the initiative, referendum, and other tools that allow voters to make laws directly—has spread to 113 nations.

California, which has soured on America’s faltering political system, is in a position to build a new kind of democracy that combines U.S. traditions with international ideas.

I met Chang last year at an international direct democracy conference in Rome—another place where his idea has traction. One day earlier this month, as Chang set up a campaign operation in the East Bay, he got news that a court in Taiwan had turned aside a major legal challenge to his initiative.

“This idea is something the whole world needs,” says Chang. “The right to vote no is a fundamental human right.”

His concept of “the negative vote” is straightforward. Today, in elections, we are allowed to vote for one candidate in each race. Chang proposes to give voters in Berkeley, and ultimately all over the world, the ability to use that one vote to cast a ballot against the candidate instead. In such a system, each candidate’s tally of votes would be a net—between her number of positive and negative votes.

Chang offers several reasons to make this change. First, the current system is wrong in encouraging us to vote for a candidate in each race, even when we don’t support any candidate. Furthermore, the option of a negative vote would boost voter participation. One reason people give for not voting is that they don’t like any of the candidates; the negative vote would give such naysayers the option to vote against the candidate they dislike most. Chang’s organization commissioned a survey from the RAND Corporation suggesting that, in a U.S. presidential election, offering the negative vote would draw 16 million more people to the polls.

More broadly, Chang argues that the negative vote would create an incentive for politicians to collaborate and to behave more responsively, for fear of drawing negative votes against them.

The idea also has a feature that could be helpful in local races, where there is so little interest in politics that often only one candidate appears on the ballot. “Should I only have the option to vote for the one candidate on the ballot, but not against?” Chang asks rhetorically. “The answer is obvious: I should have the right to say ‘No!’ If I am only allowed to vote ‘Yes!’ you would think I am living in North Korea.”

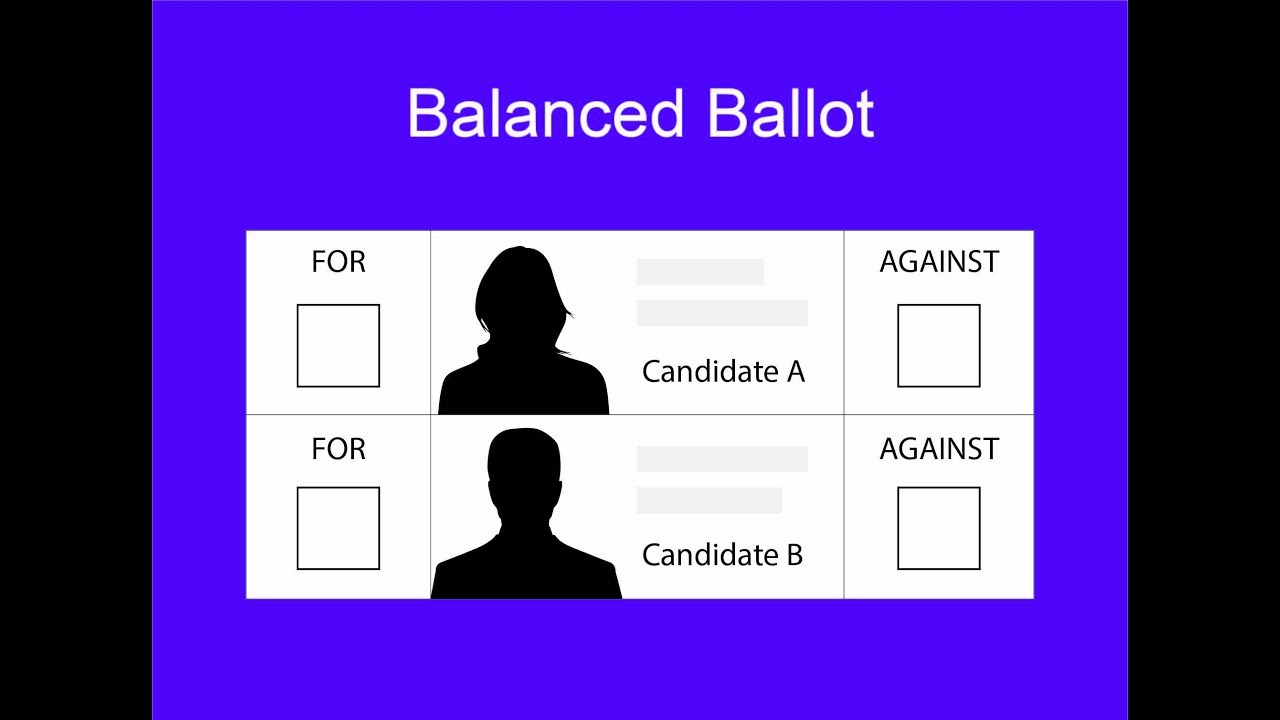

The “balanced ballot” is how a negative vote would appear to voters. Courtesy of the Negative Vote Association.

Chang admits he is an unlikely champion for a California democratic reform. Raised in Taipei, he was sent to Massachusetts for high school and went on to Harvard for college and Wharton for his MBA. But while his siblings and their kids would settle in the U.S., Chang moved back to Taiwan because his parents were there and he wanted his own children to have a Chinese education.

As he traveled the world during his banking work, he grew more concerned with signs of weakening democracy in many different countries. The inspiration for the negative vote came on a 2010 trip to Israel, when he learned about that country’s complicated government and its problems.

By 2012, Chang had begun working on the negative vote project. The idea was not new: the Venetian Republic, the Venice polity that ran from the end of the Roman empire to Napoleon’s conquest in 1797, had negative voting. Today, the negative vote is used in the selection of the United Nations Secretary General, with nations permitted to vote against a candidate as well as for one. (Chang notes that Brazil and India also permit “none of the above” votes, but that is not the same as negative vote).

Chang has slowly built support across the political spectrum in Taiwan; his prominent endorsements include three former premiers, Taipei’s current mayor, and Shih Ming-teh, known as “Taiwan’s Nelson Mandela” for having served longer in prison than any other opposition figure under the Kuomintang party’s nearly five decades of rule. The negative vote addresses two Taiwan-specific issues. First, since Taiwan gives political parties NT$50 and candidates NT$30 in public funding per vote received, the idea is pitched as a way for voters to cast a ballot without helping fund political entities they don’t much like. Second, the idea is seen as one antidote to Taiwan’s problems with illegal vote-buying.

In the U.S., Chang has seized on Berkeley because it’s the closest thing he has to an American hometown; his son lived there for many years. Berkeley is a small city with a charter, which allows it to enact new election ideas that don’t conform with state laws. Qualifying an initiative for the ballot there is also relatively cheap—about $50,000. But the city is also famous globally, and Chang is eager to connect with its university’s scholars in the hopes they will spread his idea around the country and the world.

Chang has been making regular visits to the city from Taipei, attending parties thrown by activists and chatting up city officials. I met up with him at Berkeley’s city hall, where he was talking with former city councilman Kriss Worthington, now an advisor to the mayor, about the best process to draft an initiative.

In the Bay Area, Chang hasn’t gotten much traction with his argument that the negative vote would discourage extremism; most people are partisans and not so fond of compromise, he says. But in conversations I witnessed, people were intrigued by the idea that it would boost voter turnout. And Bay Area folks love it when Chang explains how, if the 2016 presidential election had been run with negative votes, Donald Trump would have lost because of all the votes against him.

Berkeley offers one distinct challenge. It no longer has the American system of voting for just one candidate; voters actually rank candidates in order of preference—1, 2, 3. Chang says that he proposes to keep those rankings, but allow Berkeley voters to negatively rank candidates—as well (-1, -2, -3, etc.)

That would offer voters a choice—who do you dislike most?—that fits our time.

There are efforts to adopt negative voting in Afghanistan, Argentina, Denmark, and Poland, and Chang is also beginning to organize in Honolulu, where another of his children lives. In 2020, Chang hopes, Berkeley and Taiwan will vote for the negative vote.

Then, he hopes the whole world will become more positive, by going negative.

Send A Letter To the Editors