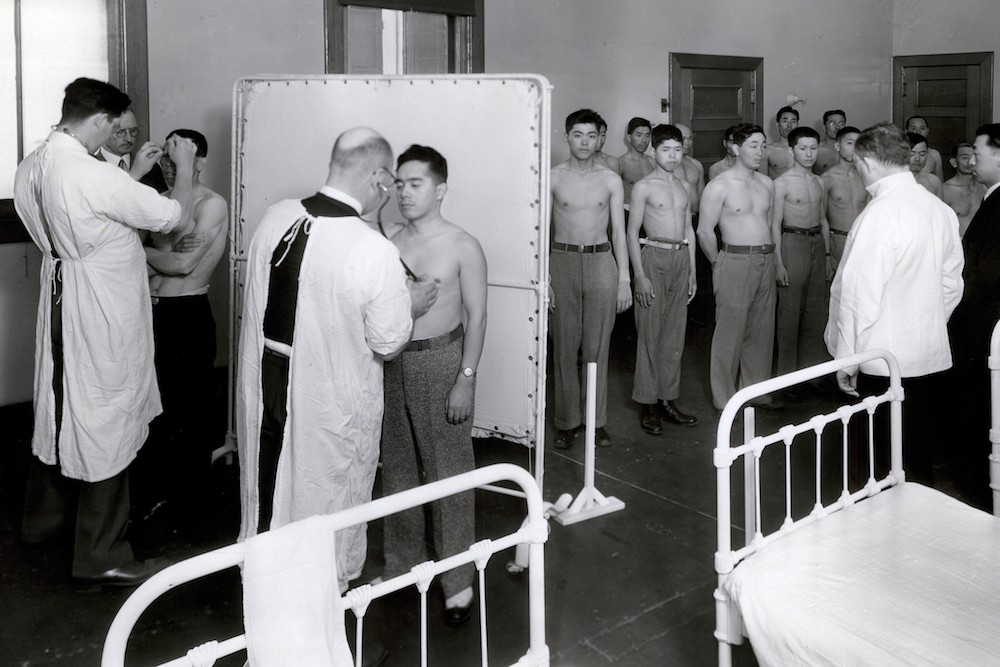

Medical officers at the Immigration Station at Angel Island, California, examine immigrants for trachoma, an infectious disease, in 1931. Courtesy of the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Alan Kraut is a historian at American University who has studied the nexus of immigration and health for many years. Zócalo spoke to Professor Kraut to understand the role history plays in our current understanding of the subject, as well as how he himself has absorbed new concepts of wellness brought to this country by immigrants.

What’s the connection between health and immigration?

From my perspective as a historian of immigration and refugee policy, those who come to the U.S. bring with them their group’s unique cultural attributes, including cuisine, music, and perspectives on life in the world. Included in every newcomer’s cultural identity, but often overlooked, is a perspective on health and disease and therapeutics. So when I wrote Silent Travelers: Germs, Genes, and the Immigrant Menace, one of the things I wanted to explore, in addition to the stigmatization of the foreign-born for particular diseases, was to look at the perspectives on health and wellness these newcomers brought with them and how much of it was retained and how much of it changed in a different medical environment.

Historically, how did Americans see immigrants in terms of health?

Before the United States became an independent nation, each colony had quarantine regulations. Quarantine regulations and procedures were regarded by colonial governments as critical defenses against disease coming from abroad. For much of the nineteenth century, state governments were responsible for quarantine enforcement and the inspection and interrogation of immigrants. The physicians who inspected newcomers at state facilities were often volunteers. Their purpose was protecting people from diseases—and one more very important thing: to make sure that those who were coming into the United States were sufficiently healthy and robust to be economically productive and not a burden on the community.

How did matters of health and disease shape Americans’ perceptions of newcomers from abroad?

At times, opponents of immigration blamed different groups for specific diseases. In 1832, a cholera epidemic that ravaged the east coast of the United States was blamed on Irish immigrants. The idea was equating the arrival of the foreign-born with something bad—with disease—or with immigrants who might become burdens on their hosts. In the same way, the Chinese were often accused of bringing leprosy to the U.S. By the end of the nineteenth century, Italian immigrants were being blamed for bringing polio to the U.S. and Eastern European Jews were stigmatized for tuberculosis. There was what I call a double helix of health and fear. The fear of disease from abroad has often been appropriated by those who oppose immigration for other reasons, a pattern which you can see to this day.

How have immigrants changed how Americans understand health?

Borrowing from abroad is part of the cultural history of the United States and it includes the world of medicine and therapeutics. Chinese medicine arrived here when the first Chinese came in the 1850s. They brought with them their understanding of herbalism, their concoction of teas, their use of those therapeutics. The traditional Chinese medical understanding of what made people sick was very different from in the west.

It isn’t really until the 1970s when acupuncture becomes popular in the U.S., but the herbal remedies and the teas came earlier. Americans’ use of Chinese therapeutics continues up to the present day. When a community migrates to the United States, members of that community bring their definitions of health and their therapeutic modalities with them. Some are adopted by their hosts.

In the South, before the Civil War, many Southerners took the advice and remedies of slaves and slave descendants, cures that had been brought by word of mouth from Africa.

How have immigrants changed Americans’ ideas of what health care is?

One of the most obvious ways is through foreign caregivers themselves. At times in our history, we’ve had insufficient doctors or nurses. Foreign-born caregivers have come become important members of our medical community. Think of what Filipino nurses did when the U.S. had a serious nursing crisis in the 1950s and ‘60s.

Caregivers give more than labor though. They change our conceptions of health care in a subtle kind of way. Caregivers are obligated to observe the medical standards of the U.S. but their view of the patient-doctor relationship is sometimes different from that of native-born Americans. Some caregivers from other cultures insist on an authoritarian role for the physician. Patients should comply with the prescribed therapy because the doctor is the “boss.” However, in the United States, patients frequently reject an authoritarian approach.

But another example, in the other direction, can occur in the care of the elderly. One of my friends placed his mother in a rehab facility and he noticed that there were a lot of West Africans working in the facility. One of the supervisors said that the workers, who were all from the same culture, had tremendous respect for the elderly and found them to be worthy of respect and deference. And so, he said, I hire them because they’re great—they’re compassionate and gentle. There’s a cultural component here and it spills over into how people are treated and what our expectations are for treatment and care for ourselves and our loved ones.

How have you changed your own ideas about health and wellness?

When I had shoulder problems, I went to an acupuncturist. This is something I wouldn’t have known much about or certainly done before the 1970s. The concept of acupuncture, accessible to me, seemed worth trying and I had great results. I found that a therapeutic technique derived from another culture could be of immediate benefit, could relieve my pain. It confirmed my broader belief that the cultural diversity derived from immigration enriches us as a nation and often touches our lives in the most positive of ways.

Send A Letter To the Editors