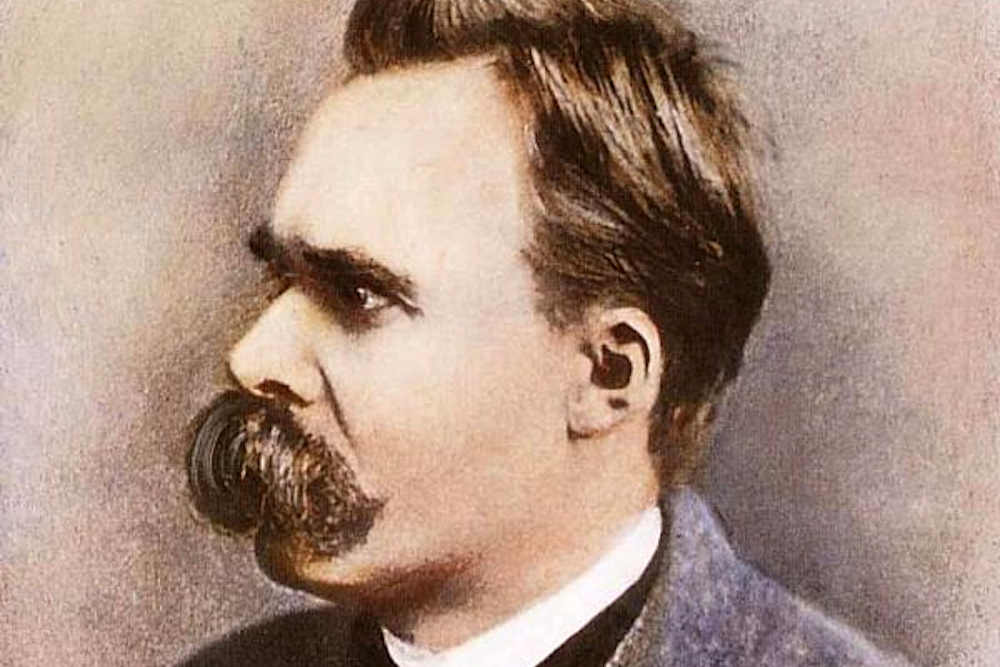

German philosopher and nihilist Friedrich Nietzsche. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

There has been, quite literally, much ado about nothing of late. Shadowing the rise of Donald Trump is the rise of what Friedrich Nietzsche called the “uncanniest of guests”—namely, nihilism. Google the words “Trump” and “nihilism” and more than half a million links light up. At the very least, nihilism is the most ubiquitous of guests.

But what shade of black are we discussing? A representative sampling includes: “The Year Hope Began to Triumph Over Trump’s Nihilism,” “Trump’s Leverage in the Shutdown Fight: His Own Nihilism,” “Trump’s Mindless Nihilism,” and “Trump, the Nihilist We Deserve.”

It is tempting to say that never have so few—one man, really—done so much for nothing. But it would be more accurate to say that never have so many headline writers and pundits done so much to mislead us as to the true nature of nothingness. Donald Trump has a single overriding concern: Donald Trump. This is narcissism—morally and philosophically empty—but it is not nihilism. Our uncanny guest deserves better than this. Because, while nihilism has little to do with our president, it has much to do with our lives.

Derived from the Latin nihil, or “nothing,” the term formed in the brackish waters of early 19th-century German philosophy, where the currents of idealism and romanticism flowed into one another. Popularized in 1862 by Ivan Turgenev’s brilliant novel of generational conflict Fathers and Sons, the term came to signify the repudiation of an utterly corrupt political and social system. Crucially, though, Bazarov, the novel’s young nihilist, was driven not just to destroy an existing and unjust world but also to build a new and better one.

But ever since the late 19th century, nihilism has been indelibly associated with Nietzsche. Remarkably, it was only 130 years ago this month that Nietzsche—a native German who despised everything German, the son of a Lutheran pastor who declared God was dead, and a seeker of truth who denied the very possibility of truth—collapsed on a street in Turin while embracing a horse mercilessly whipped by its owner. Eleven years later, in 1900, Nietzsche died, leaving behind a philosophical legacy with which we have wrestled ever since. Not surprisingly, Nietzsche predicted this very outcome: “I am frightened by the thought of what unqualified and unsuitable people may invoke my authority one day. Yet that is the torment of every teacher … he knows that, given the circumstances and accidents, he can become a disaster as well as a blessing to mankind.”

In essence, Nietzsche transformed Immanuel Kant’s imperative sapere aude, or dare to know, into an equally imperative demand: dare to accept the consequences of knowing. As he affirmed in The Gay Science, God is not only dead, but he died at our hands. By dint of scientific and intellectual progress, we have dug the ground out from beneath our own feet. The drive for truth and certainty instilled by Christianity has led not just to its own unmaking, but also that of foundations for right and wrong, good and evil we thought were unchanging and universal. Under the merciless light of reason, we can no longer, Nietzsche insisted, “esteem the lies we should like to tell ourselves.”

This relentless urge for truth, the madman in The Gay Science declares, has “wiped out the whole horizon” and “unchained our earth from her sun.” What we have done, Nietzsche claims, we can never undo. More ominously, what we have done we haven’t begun to understand. It is this dizzying and dreadful prospect—one subsequently scaled by writers like Fyodor Dostoevsky and Joseph Conrad, Samuel Beckett and Flannery O’Connor—that Nietzsche understood by nihilism.

But today’s nihilism isn’t what it used to be. We live in an age where meaninglessness is, well, meaningless. We have become either oblivious or indifferent to the loss of absolutes and find ourselves unburdened not only of the weight of meaning, but also the sense of loss that once accompanied it. When we now look into the Abyss, Lionel Trilling observed, the Abyss smiles back and says: “Interesting, am I not?”

In a recent interview in the New York Times Book Review, the author Candace Bushnell remarked that as a teenager, she was obsessed “with anything that was considered nihilism … For some reason, nihilism felt like the right sort of mentality for an 18-to-21-year-old. Then, of course, one grows up and has to get a job.” Yes, one does grow up and one does get a job—at least if one is fortunate. But neither of these events means nihilism—or, more accurately, the human condition reflected in the term—goes away.

Yet it is easy to think nihilism has disappeared when the word does not stop appearing. According to pundits and politicians, nihilism fuels the Islamic State’s massacres of human beings and mutilations of ancient religious sites; it feeds our government’s paralysis in a take-no-prisoners approach to American politics; and it frames the void at the center of popular entertainment, from cinema and television to video games and the Internet.

Looming at the edges of our world in the form of black-clad and armed fanatics, nihilism lurks at the world’s very center in the technology we use, as the late Neil Postman observed, to entertain ourselves to death. From pop nihilism and post-nihilism to Islamic nihilism and environmental nihilism; from compassionate nihilism and Darwinian nihilism to nihilism lite and virtual nihilism—to name just a few—our age has spawned a dizzying number of variations on this most dire of philosophical responses to the world.

Herein lies the danger. By rendering nihilism banal, it no longer seems baneful. Given the political and social consequences of what, for example, is now unfolding in our capital, this might seem a small matter. Yet it pays to distinguish, say, between narcissism and nihilism. It pays for a simple reason: Nihilism is not, as one of the above headlines insists, “mindless.”

As the cases of Dostoevsky’s Karamazov or Conrad’s Kurtz remind us, the recognition of nihilism results from a kind of mindfulness. It has been the end point of fictional and historical characters that have thought long and hard about the human condition. The descent to the heart of darkness experienced by both of these characters is neither thoughtless nor gormless; it is, instead, deliberate and desperate. In order to register the horror, the horror, our eyes need to be wide open.

In the opening pages of his philosophical essay The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus announces: “There is just one truly important philosophical question: suicide. To decide whether life is worth living is to answer the fundamental question of philosophy. Everything else is child’s play; we must first of all answer the question.” This question confronts us the day that, finding ourselves in “a universe suddenly divested of illusions and light,” we nevertheless insist on meaning. We can, of course, live without reading the latest tweet or chyron. But can we, as Camus asks, live without appeal to metaphysical or theological authority? This is the fundamental question—one easily lost sight of amid today’s distractions—posed by nihilism.

Send A Letter To the Editors