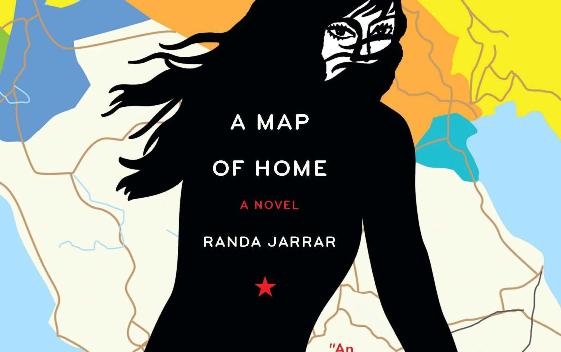

Randa Jarrar’s first novel, A Map of Home, tells the story of a girl coming of age in the Middle East and in middle America — Texas, to be precise. Jarrar chatted with Zócalo about her inspiration, how closely her character’s story hews to her own, and the work of Arab American writers.

Q. How did you come to write this novel, and when did you know you wanted to be a writer?

A. I have this really old fake passport I made when I was 10, and it shows all my different identity crises at the time. It’s an American passport, but my nationality is Palestinian. Under occupation it says ‘author.’ I always wanted to be a writer. I also wrote a lot, and made these cute little documents, little poetry books and passports. It’s an old practice for me.

I grew up in Kuwait and my mother was Egyptian and Greek, and my father was Palestinian. We traveled a lot to the West Bank and Egypt when I was growing up, and then moved to the U.S. after the first Gulf War, after 1991. I moved to Texas by myself in 2000, well, not by myself but with my child, who was two at the time. My life and my character’s life are similar, but also, in other ways, they really differ. People who read the book assume that because my character moved to Texas after the first Gulf War, I did too, but that’s not the way it went. I moved to a really stuffy part of New York and Connecticut. I didn’t want to write about that. My move to Texas was a choice I made, not my parents, so I thought for my character, it would be interesting to infuse her narrative with that agency. And I think it worked.

Q. Were you ever tempted to write memoir?

A. I’ve written short nonfiction pieces but I prefer to read fiction. I’m thinking about writing a nonfiction book about my experiences as a teen mom, but the novel was always going to be a novel. I just fictionalized my history, and my parents’ histories, and I don’t think I could’ve written the book as nonfiction. I would’ve gotten bored, or I wouldn’t have felt like I was giving the energy of the story justice. I wanted to read a novel that discussed my geographical background and my historical background, not an exact memoir. I’m always jealous of other authors, and not just ethnic minorities, who have had the experience of approximating their life stories in fiction. But really, if a young white woman grew up in Ohio and wrote about a woman from Ohio, people are going to assume it’s a memoir. But if a man from new York writes about a character from New York, nobody assume it’s a memoir. Because of my specific background, people assume it’s a memoir, it’s nonfiction, and it isn’t. I just wanted to see a character that had my exact specific cultural history and geographical background.

Q. Are there other Arab-American characters in literature or elsewhere that you identified with, or did you feel as though you had to create one that made sense to you?

A. I definitely felt like I had to create my own Arab American character. There weren’t any I could relate to, not only in fiction but also obviously in popular culture. I don’t relate to any of the Arabs on TV. They’re not real, they’re not authentic-they’re stereotypes. I really like other Arab American writers, like Diana Abu-Jaber, Alicia Erian, Rabih Alameddine. I like all three of these writers but the two women, their novels tend to be about Arab Americans who were born here, and the male writer, his novels tend to be about gay men. They tend to be a lot older, and he is older than me. I felt there wasn’t this kind of character available, and I definitely wanted to create it. I wanted to create Nidali, the narrator, because I wanted her to exist in the landscape of narrative fiction, and Arab American literature too.

Q. Can you tell me more about Nidali?

A. Nidali is very bossy, loud, profane, funny, and she’s obsessed with her family’s history and her identity, and with how her new, sort of post-postcolonial self fits into the larger world she inhabits. She spends a lot of the novel trying to figure out who she is and where she belongs in the grand scheme, not just with her family, but with her international self, and who she want to be as opposed to who she is expected to be. Her family is full of failed artists, her dad is a failed poet and her mom is a failed concert pianist, and their main identity is rooted in their failure as artists. Their secondary identity is given to them by their own families, their places of origin-her mom’s as an Egyptian, and her father’s as a Palestinian. Nidali comes out of that, being a sort of mixed child in a somewhat homogenous culture. Even though they’re Arabs, her parents are from two different countries and it’s still seen as somewhat bizarre and out of the norm. From the very beginning, she has this feeling of being out of place, or being strange, or being a mix of things. Throughout the novel, she explores this mix, and tries to figure out a way for herself to be whole in the face of all this mixing.

Q. You often use humor, and Nidali’s child-like perspective, to discuss the serious political topics. Was that a deliberate choice, or is it just the tone you prefer to strike?

A. I really wanted the novel to be funny. I didn’t see the value of writing a novel about all the serious stuff in a serious way. I like to take serious things and make fun of them and satirize them and embellish them and inject humor into them. That is one of the only ways to deal with serious stuff. I think this is common in a lot of submerged populations, like Jewish authors, African American authors, Asian American authors. Not all of them do it, but there tends to be a strain of humor in all the depression. Nidali’s humor is gallows humor, so I thought it was well-suited to this sort of story. I didn’t want it to be so self-important.

Q. How have American perceptions of Arabs changed since the Gulf War, if at all?

A. I think American perceptions of Arabs didn’t really change, or weren’t really tapped into or challenged, till 9/11. I don’t think Americans had to think about Arab since before then, except as a distant menace or something to deal with from afar. I think after 9/11 Arabs and Arab Americans experienced hyper-visibility. Overnight, people were interested in Arab and Arab Americans, but unfortunately there was confusion between Arab Americans and Muslims and Muslim Americans. I don’t think most Americans know the majority of Arab Americans are Christian. Arabs have been immigrating to the country since the early 19th century. But since 9/11 people were more interested in the Islamic aspect of Arabs and Arab Americans, because they were trying to figure out why 9/11 happened. I think definitely, if you see the number of published novels and stories before and after 9/11, you’ll see a huge discrepancy between them. I think publishers were more willing to take on Arab American authors. There was a readership for it.

Q. Do readers or publishers expect Arab Americans to tell a particular type of story, and how have you experienced that? Is it frustrating?

A. I’m not frustrated by other people’s expectations because I don’t care. Obviously there’s a part of me that absorbs, just like any writer, expectations from readers, whether they’re other writers or members of their workshop or their family or readership from an earlier book. There’s that level of expectation that I have to deal with anyway, and a writer’s job is to shut out those voices and tell the story that the writer is meant to tell, the inner story. It’s very hard for all writers to do that.

I think readers tend to like stories by Muslim and Arab American women that detail sort of women’s oppression. Instead of a rags-to-riches story, it’s more of a hijab-to-freedom story. It doesn’t occur, I think, to most Americans, or not just Americans but the general population, that a woman can wear a hijab and can be the mistress of her own household and her own life and all that. I think there is a preoccupation with that kind of story.

There is also I think an expectation that an Arab American writer is going to tell sort of whimsical, magical stories, that Arabian Nights, genie-in-a-bottle sort of stereotype that an Arab American is an adept storyteller. That is what people expect, fantastical stories about ridiculous stuff, just bullshit. I think the oppressed woman, the ornate magic story, and maybe a third strain would be the hyper-political novel, or if not hyper-political, the somewhat didactic novel, not even set in America, or set in America featuring new immigrants, and showing the politically charged aspect of being Arab American or Arab post-9/11. Readers expect these books to be testaments of on-the-edge fundamentalists, not quite someone who is a fundamentalist, but how they might become one, how they might be understood. I think those are the preferred stories that are expected. There are more, but those are a few that seem the most pronounced, the ones that I’ve seen.

Q. Given those expectations, how have readers and reviewers reacted to your book? Are they surprised to see familiar-seeming characters?

A. Yeah, when the book first came out, some reviewers said that it was basically about adolescence. It’s about what growing up is like, for anyone. I think maybe some readers were surprised by a young Arab American girl growing up, that her growing pains and aches were exactly the same as anyone else’s. That’s one of the cool and great things about fiction. It can really bridge gaps like that, where a reader might expect the Other with a capital O to be so other, and where we discover that actually they’re not. We have similarities, we are all human. In some point in my life I would’ve found that offensive-we’re obviously all human, what did you expect, a story about being a donkey or some other beast? I think now the way I see it is that it’s sort of sad that we’ve become so disconnected. There are not enough stories about Arabs and Arab Americans and Muslims and Muslim Americans and tons of other minorities are not getting their say.

Q. You’ve discussed some of the expectations for Arab American writers, but what about for female writers generally? Have people assumed your book, for instance, would be a young adult story just because it’s written by a woman about a young woman?

A. Initially, people were saying maybe the book was young adult, and it’s great if a 14-year-old or other young person wants to read this book. I made sure it was accessible to pretty much anyone over the age of 13 or 14. Of course, I don’t think if I were a man writing about a young boy that that would’ve happened. So many women writers have written books about the young, and there is definitely sexism there when it comes to telling stories about girlhood. Girlhood is not deemed as important or literary or grand as boyhood. I think that’s going to change. Whether they like it or not, there are more women writers now and readership is more female and things are changing.

In terms of the sexuality in the book, I really felt it was important for my character to be honest in general. So when the sexual aspect came up, and she’s a young girl growing up, I really wanted to be sure that she didn’t shy away from it as a topic. A couple of reviewers said that if it hadn’t been profane and if the sex had been toned down, the book would’ve been a great young adult book. But that comment makes an assumption about young adults, that they don’t think about sex or they don’t hear the same language around them every single day.

Q. Where would you say is home for you?

A. Right now I’m at my desk. I’m surrounded by these little toys and photos and objects that I’ve collected over the years. I’m happy here. It doesn’t matter where I am. I don’t think I need to be at a certain place to feel at home.

Send A Letter To the Editors