John D’Agata, author of The Lost Origins of the Essay, came to be a writer through what seems an unusual route: studying Latin. He began with a tutor as a child and continued with the subject all through school. “It felt like a private language, a private world that was mine,” he said. He majored in it in college until realizing what he really liked about Latin wasn’t quite the language, but the texts. “The huge majority of prose Latin text is essay,” he explained. Now he teaches the subject at the University of Iowa, “in a graduate program dedicated to what the university calls ‘nonfiction.'” Below, he discusses with Zócalo why he’d rather not use the term nonfiction, or even creative nonfiction, how the essay got lost, and what exactly it is.

Q. Briefly, what is the essay, particularly for someone who imagines it’s what they wrote in high school?

Q. Briefly, what is the essay, particularly for someone who imagines it’s what they wrote in high school?

A. The essay is a rumination. The essay is an attempt to figure something out, but it is not necessarily a promise or a guarantee that that issue or that question or that problem will be solved, answered or indeed figured out. It’s an inquiry, so what it promises is thought.

And that’s what I love about essays – the chance to watch a writer’s mind in action. That’s actually one of the most common definitions of the essay, “a loose sally of the mind,” as I think Samuel Johnson put it. And that’s what I love about it, its casualness, as well as its ability to make wild formal adventures. So I love its versatility. And also that it relishes risk.

The term essay comes from a middle French word, essai, which means a test or trial or experiment – an attempt. Therefore, I think that since every essay is an attempt, it is also inevitably an apprenticeship to failure. It doesn’t matter what kind of risk an essay may wander into-it could be an emotional risk, it could be an intellectual risk – because it’s that jumping off the edge of the rulebook that I find most exhilarating as a reader.

Q. Why do you claim the origins of the essay are lost?

A. Fair question. By lost I mean two things. First, I do mean literally “lost.” Some of the texts in this anthology have been lost, or at least they are texts that we’ve lost track of. They certainly felt like a discovery to me. Some of these texts really haven’t been widely circulated or widely read in the literary world. So by “lost,” I really do mean, Hey, let’s remind ourselves that these texts exist, and let’s celebrate them.

But I think “lost” means something else, too. And I guess this is the more political argument of the book: that some of these texts ought to be reclaimed as essays. I know that probably the majority of readers would disagree with me if I were to say William Blake’s “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell” is an essay, because for 200 years we’ve enjoyed it and known it as a poem. The same is true with the Borges short story that’s in the anthology, and the same could be said about Marguerite Yourcenar’s text, or Basho’s or Rimbaud’s. Each of these is widely celebrated as something other than essay. What I would like to do is plant a little essay flag in them, however – not necessarily in order to say that they are essays, that they aren’t stories or poems or whatever it is we know them as, but instead in order to ask what might happen if we were to frame them as essay? Conceptually speaking? Does something change? Do we read them differently? Does the implied mechanism of “essaying” alter not only how we approach the texts but also perhaps even the texts themselves? And, perhaps most importantly, does our perception of what an essay is change?

Most essayists feel deeply the burden and blessing of the essay’s diversity. As you put it earlier, the great majority of readers probably interpret the essay as an exclusively expository thing – as a vehicle for a discussion about history or politics or even other types of literature. We’re used to writing essays about “issues.” It’s in fact quite rare in English classes to be presented with an essay and asked to consider it as literature in an of itself. So the point of this anthology, and of making it a part of a three-volume history of a certain kind of essaying, is simply to remind ourselves that texts that are legitimately essayistic are also genuinely artful. And that such texts have been around for about as long as we’ve had any other kind of literature. My hope is that this might change some readers’ opinions about what an essay is or could be, and to encourage an approach to reading essays that expects from them a certain artfulness.

It sounds like a simple desire, but the perception of the essay as fundamentally un-artful is unfortunately common. I happen to teach at a university that has been teaching creative writing probably longer than any other place in the U.S.. At the very least, it’s considered the most “prestigious” place at which to study creative writing. But the dirty little secret about our school is that the essay as a literary form is segregated from poetry and fiction. The writing program I teach in is in fact entirely different from the program that teaches fiction and poetry. When students apply to Iowa, they are not technically applying to what is formally called the “Creative Writing Program” at the University of Iowa, because at the University of Iowa “creative writing” is officially only fiction and poetry. Our program, therefore, is called the “nonfiction writing” program, immediately suggesting of course that the work being done by my students in the program is fundamentally not “creative.” What is it then? Well, apparently it is something “else.” And I find that heartbreaking, and not only on behalf of my students, but also when I consider how that simple alteration inevitably changes a reader’s attitude toward a text when he or she is trying to engage it. I think it’s dangerous when people start defining what is it “art” and what is not. I don’t think it’s healthy for literature. And certainly not for the essay. And it’s never been particularly useful for art.

Q. You note early in the book that the Roman era didn’t produce great essays in part because it was the first information age. Does that mean now is an even worse time for the essay?

Q. You note early in the book that the Roman era didn’t produce great essays in part because it was the first information age. Does that mean now is an even worse time for the essay?

A. Well, ironically enough, I feel like we’re living through a significant moment for the essay, a period during which we’re remembering what the form is capable of. And that’s exciting. Graduate programs like the one I’m teaching in, devoted to nonfiction, are springing up and increasing their enrollments at a much faster pace than fiction and poetry. We’re seeing people not only explore different modes of the essay, but also experimenting formally within the essay. And perhaps this is because the onslaught of information is causing a kind of backlash among young essayists who want to see what else this form might be able to do other than dispense data. But I would also say that I don’t think this is only happening in the essay world. There is clearly a renewed interest in hybrid work, in moving between genres or even in planting a stake in some realm outside of genre altogether.

Q. Are there any essay writers working today you particularly admire?

A. My favorite living essayist is Joan Didion. It’d be hipper for me to say that I’m totally into some obscure young writer you’ve never heard of. But I’m not hip and Didion is good she’s even fascinating when she isn’t entirely on top of her game. But I also admire her because she has allowed herself to evolve dramatically, and to the chagrin of a lot of her earliest readers. If we were to compare her first essays, like in Slouching Toward Bethlehem and The White Album, with her most recent work in a book like Political Fictions, there’s an astonishing difference between her approach to essaying. There was a brief little break she took from that evolution, that arc, when she put out the memoir that was wildly popular, about her husband’s death, The Year of Magical Thinking. Partially it was so popular because it reminded people of the old Joan Didion, of this mind that was incredibly intelligent but also felt deeply vulnerable. And it’s that raw emotion that I think really captured people’s hearts. Her other more recent work however isn’t as adored. This other recent is pointed, argumentative. Her syntax is like a steel trap. Once you enter into it there’s no chance of coming out on the other end not believing what she wants you to believe. These are technically brilliant essays that are argumentatively razor sharp. No subtlety, no vulnerability whatsoever. I read an interview with her about this once, a really great interview during which she was asked why she thought people weren’t that into these more recent “rhetorical.” And Didion replied, “because no one likes a know-it-all.” And I think she’s right. But I think what she could have also said is that we’re still shockingly sexist in this culture, and I think the vulnerable position that Didion puts us into in these newer essays is threatening to a lot of readers.

Q. Were there any essays that you were hesitant to include in this collection because they were too far afield, or any other reason?

A. There are essays that gave me pause for a number of reasons, because there are a number of essays included that aren’t very surprising for an anthology that’s trying to say, hey, let’s remind ourselves that the essay has a wild side too. I could imagine that at first glance it’d be perplexing for a reader to find Thomas Browne’s “Urn Burial” in this book, or Montaigne or Woolf or any of the old chestnuts that appear in here. At this point, some of the essays included in here have been anthologized so much and they’re now part of our canon. But I guess what I would hope the anthology might do for these texts is provide a different context in which we can read them and therefore rediscover them, recapture that the moment in the mid 17th-century when “Urn Burial” first came out and appeared like a revelation in English prose. A lot of writers credit it with introducing the modern voice in English, and that’s a pretty radical thing for an essay to do – or for any work of literature for that matter. So even while the text these days might seem really old, in its historical it was pushing the envelope like any of the others in the anthology.

Q. How do you feel about the term “creative nonfiction”? Is it a sort of backhanded compliment to the essay, suggesting that people are interested in the form again?

A. It absolutely is. Phillip Lopate said something hilarious about that term. He said that “creative nonfiction” was the equivalent of “good poetry.” It’s definitely backhanded. But it’s also pathetically trying to dress up that term “nonfiction” in fancier and more acceptable literary terms. The term nonfiction is relatively new, only about 40 years old, but it’s unfortunately taken off and is what most people now use to refer to the genre. But I think it’s dangerous. It emphasizes the subject matter in these texts, not the art. So it’s not only a negation of genre, but it’s a negation of the imagination too. “Non-fiction” only defines the genre by what it can’t be – not creative and not art. “Fiction,” after all, comes from the Latin word for “to shape,” or “to arrange.” So the idea of something being nonarranged, or nonshaped, suggests that it isn’t therefore molded, that it hasn’t been thought about and wrestled with and forged into something new. Art is about shaping, sculpting, making something out of the raw material of the world. The term “nonfiction” suggests that it is merely information, though – just raw data. The reason why I use the term “essay” over “nonfiction” is because essay emphasizes an activity – that attempt, that trying, that experimenting. I think it opens up new possibilities for this genre. It opens up the gates of art.

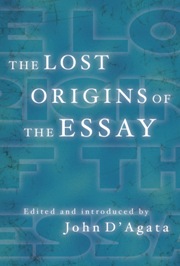

*Photo of John D’Agata by Margaret Stratton. Photo of William Blake’s tombstone courtesy diamond_geezer.

Send A Letter To the Editors