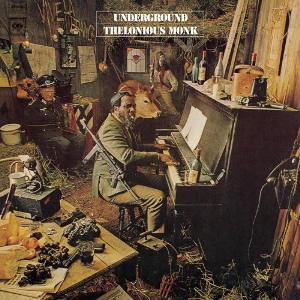

You don’t have to know Thelonious Monk to know the Underground LP. Over the past few years, whenever I mentioned to anyone that I was writing a biography of the jazz pianist and composer, even those who had never heard the music knew the iconic and bizarre cover image on Underground: Monk playing an old upright piano with a machine gun strapped to his back, barricaded inside what was supposed to be a secluded haunt of the French counterculture. It’s often assumed that Underground marked the height of Monk’s powers. On the contrary, Underground was Columbia Records’ desperate effort to resurrect an artist whose dismal sales were a drag on the label, a common yet dramatic story of a corporate giant trying to turn vintage wine into popular confection. Released in 1968, when rock and roll was eclipsing jazz, Underground tried to make Monk an icon for youth.

You don’t have to know Thelonious Monk to know the Underground LP. Over the past few years, whenever I mentioned to anyone that I was writing a biography of the jazz pianist and composer, even those who had never heard the music knew the iconic and bizarre cover image on Underground: Monk playing an old upright piano with a machine gun strapped to his back, barricaded inside what was supposed to be a secluded haunt of the French counterculture. It’s often assumed that Underground marked the height of Monk’s powers. On the contrary, Underground was Columbia Records’ desperate effort to resurrect an artist whose dismal sales were a drag on the label, a common yet dramatic story of a corporate giant trying to turn vintage wine into popular confection. Released in 1968, when rock and roll was eclipsing jazz, Underground tried to make Monk an icon for youth.

It was always about the cover. Columbia hired the hip design team of John Berg and Dick Mantel to do the job. They built an elaborate set that included a couple of chickens, a cow, the accoutrement of war, bottles of vintage wine, a slim young model dressed in the uniform of the French Resistance, and a Nazi prisoner of war tied up in the corner. The spectacular photo tapped into contemporary images of revolutionary movements, but rendered them benign by making reference to the “Good War” against fascism. The press release evoked the spirit of youthful rebellion: “Now, in 1968, with rock music and psychedelia capturing the imagination of young America, Thelonious Monk has once again become an underground hero, this time as an oracle of the new underground.” And remarkably, the release devoted more ink to the cover art than to the music, predicting that Underground would become “the most provocative and talked-about album cover in the history of the phonograph record.” Even Gil McKean’s liner notes obsess over the image – he manufactures a fictional account of Monk as a World War II hero reliving his glory days: “With a cry of ‘Take that, you honkie Kraut!’ Capitaine Monk shot him cleanly and truly through the heart.”

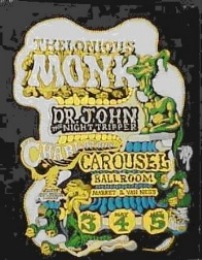

When Underground hit stores in late April 1968, Thelonious happened to have been booked to play the University of California, Berkeley, followed by three nights at the Carousel Ballroom – a San Francisco club better known for booking the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane than jazz artists. Monk played opposite the San Francisco-based rock group The Charlatans and Dr. John the Night Tripper, whose synthesis of psychedelic rock and New Orleans rhythm-and-blues attracted a young audience. Monk dug Dr. John, but did The Night Tripper’s followers feel the same way about the High Priest of Bebop? Columbia’s massive ad campaign tried to ensure they would, declaring “the beginning of a New Monk success. Because with great songs like “Raise Four” and “Easy Street” – plus another great cover photo that’s just out-of-sight, the Rock generation will be clamoring for more and more Monk.”

When Underground hit stores in late April 1968, Thelonious happened to have been booked to play the University of California, Berkeley, followed by three nights at the Carousel Ballroom – a San Francisco club better known for booking the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane than jazz artists. Monk played opposite the San Francisco-based rock group The Charlatans and Dr. John the Night Tripper, whose synthesis of psychedelic rock and New Orleans rhythm-and-blues attracted a young audience. Monk dug Dr. John, but did The Night Tripper’s followers feel the same way about the High Priest of Bebop? Columbia’s massive ad campaign tried to ensure they would, declaring “the beginning of a New Monk success. Because with great songs like “Raise Four” and “Easy Street” – plus another great cover photo that’s just out-of-sight, the Rock generation will be clamoring for more and more Monk.”

That the “Rock generation” did not run out to buy Underground surprised no one save Columbia’s marketing department. They mistakenly believed that selling Monk, or jazz for that matter, was all about packaging and the music was secondary. Monk fans and jazz lovers bought Underground not for the photo, but because he delivered four new compositions. And yet, while sales were respectable, the reviews were mixed.

That didn’t stop Monk’s producer at Columbia, Teo Macero, from trying again. Macero desperately needed a hit. Columbia execs considered Monk a liability, but Macero hoped to prove them wrong, thinking he might win crossover appeal by replacing Monk’s usual quartet format with a hip, extravagant big band record. He wanted a bigger sound, fused with a little rock and a little R&B. So he turned to arranger Oliver Nelson, a fine saxophone player and band leader who had a reputation for making hits. But in Nelson’s hands Monk’s music was flattened out, the jagged edges smoothed over, and the record as a whole overproduced. And worse, Macero included three of his own compositions written specifically for the young pop and rock market, right down to the under-three-minute format.

When Columbia released the LP, Monk’s Blues, in April 1969, the A&R and sales departments had high hopes. But the album was universally panned. Nelson took the heat for Monk’s Blues, but privately, jazz critics like Martin Williams blamed Macero and Columbia. A couple of weeks before publishing his withering New York Times review, Williams penned a letter to Macero proposing that Monk move in the opposite direction and collaborate with artists from an earlier generation – such Milt Jackson or Lionel Hampton. Hollie West of The Washington Post echoed the sentiment publicly.

Macero heard the criticisms, but neither he nor his bosses were interested in nostalgic reunions. They were still set on expanding Monk’s audience, and that meant more rock, more pop, more R&B. Just days before the release of Monk’s Blues, Macero floated a plan for an LP with Monk and popular blues singer Taj Mahal. Although there is no evidence to suggest Monk opposed the collaboration, nothing ever came of it. A few months later, Columbia’s A&R department came up with another joint project, this time with a hot new group called Blood, Sweat and Tears, a jazz-influenced rock group with strong instrumentals and a heavy brass sound. It helped, too, that the band’s drummer was Bobby Colomby, the younger brother of Monk’s manager. Macero got A&R to authorize nearly $3,500 for the session and even asked the design department to come up with an album cover, “something Psychedelic – way out.”

But this idea, too, died on the vine, in part because Monk simply wasn’t interested. He tolerated rock and roll, but he was never a fan. When asked about the music in an interview three years earlier, he had replied, “Well, my wife tells me it gives her a stomachache. It don’t do that to me, I can listen to it, but as she explained it, it don’t have that tone and it don’t tell a story.” The closest Monk and Blood, Sweat, and Tears came to a collaboration was in March 1971, when Monk’s quartet opened for BS&T at Lincoln Center and the Coliseum in Washington, D.C. While the audience appreciated Monk’s group, they came to see BS&T. So did the press. Monk was completely ignored.

Once Columbia’s execs finally realized they could not turn Thelonious Monk into Sly Stone, they quietly dropped him after 10 years – but not before putting out Thelonious Monk’s Greatest Hits. After failing to refashion Monk into something different, and then declaring him a financial liability, Columbia’s ad promoting Greatest Hits read as bitterly ironic: “If you dig the cat in the hat, you probably look upon all Monk music as great, because it’s Monk and nobody comes close.”

-by Robin D. G. Kelley

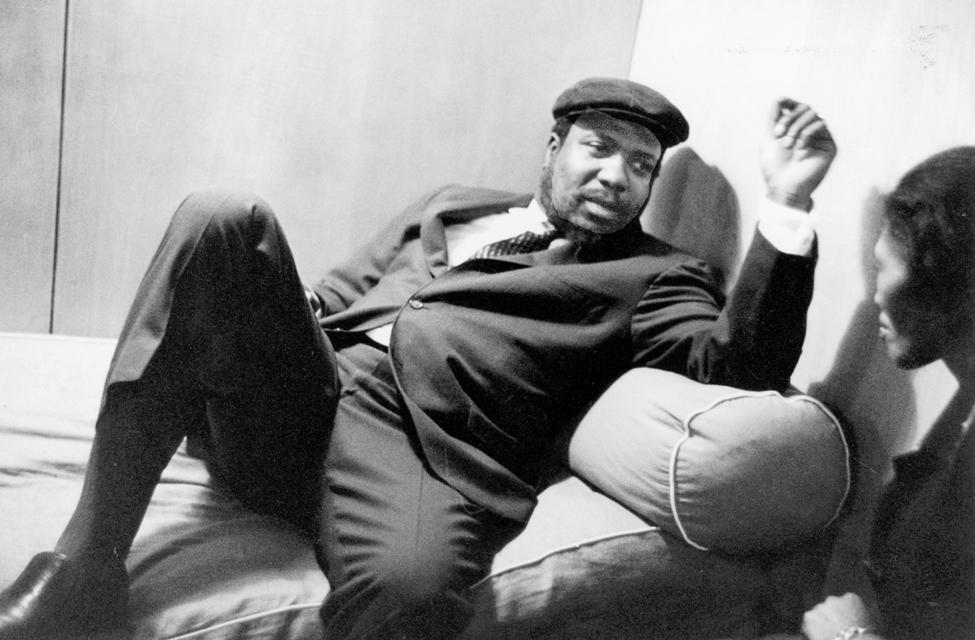

*Photos in descending order: 27 (Monk lounging with Nellie before a concert in London), by Erich Auerbach; courtesy Robin Kelley; courtesy Robin Kelley; 26 (Monk and band at the Five Spot Cage, Sept. 1958), by Marvin Oppenberg

Send A Letter To the Editors