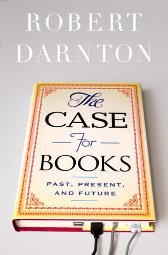

The Case for Books: Past, Present, and Future

by Robert Darnton

–Reviewed by Shahnaz Habib

The debate between physical and digital books is often framed as an either-or proposition. It seems as if the romantics who love the smell of musty books are arrayed under a flag on some medieval battlefield, while a Kindle-wielding new generation launches digital warfare from the safety of their laptops.

The debate between physical and digital books is often framed as an either-or proposition. It seems as if the romantics who love the smell of musty books are arrayed under a flag on some medieval battlefield, while a Kindle-wielding new generation launches digital warfare from the safety of their laptops.

This is why it is refreshing to read a narrative where the two factions negotiate peace. Robert Darnton brings to his The Case for Books a wide variety of experience as a historian, writer, reviewer, publisher, and currently, director of the Harvard University Library. As can be imagined, he is passionate about books, but luckily, he is also passionate about enabling access to books, and about the possibilities of technology to enhance that access.

From Darnton’s bird’s eye view of the history of books, digital technology is only the latest in a series of breakthroughs that have transformed the reading experience – just as the codex let readers turn pages instead of reading a scroll, and as the printing press and later paper enabled the preservation of text. But ultimately, according to Darnton, while digital technology has remarkable powers to disseminate text in ways that the codex cannot, when it comes to the tangibility of the reading experience and the preservation potential, the printed codex is still the clear winner.

Is it possible then to create a medium where the physical and the digital combine their strengths instead of fighting for supremacy? Print-on-demand technology is a good example of such a complementary relationship. Darnton discusses e-books at length, and in particular, his old pet project, Gutenberg-e. Designed to take advantage of the digital form as well as provide the comfort of the printed medium, Gutenberg-e produced electronic monographs in scholarly fields. In their digital form, these monographs are embedded with hyperlinks, images, music, video, and links, but depending on the individual reader’s choices, they can be selectively printed out in the traditional book form.

What makes Darnton’s discussion of Gutenberg-e truly fascinating however is his analysis of the crisis in academic publishing. With inside information from the publishing industry (and the heart-ache of a library director who shells out tens of thousands of dollars to subscribe to academic journals), Darnton convinces the reader that print and digital need to work together and can work together, in the interests of readers and writers.

Unfortunately Gutenberg-e did not take off. Perhaps it would have if it had the muscle to take on suspicious academics and booksellers. Which brings us to Google.

Darnton is not opposed to Google’s digitization of books, but he does caution eloquently against trusting Google too much. One of his most chilling sentences comes early, in Chapter 2: “Google employs thousands of engineers but, as far as I know, not a single bibliographer.” The burden of this sentence sits heavier on the mind after reading Chapter 9: “The Importance of Being Bibliographical.” There is a science to understanding how literary documents come into existence. The detective art of generations of bibliographers is why we know of a particularly slipshod seventeenth-century workman called Compositor B, who is responsible for many corruptions in the Shakespeare plays that he published. When “digitized texts are detached from their moorings in printed books,” we can expect an exponential increase in the instability of text. We can also look ahead to losing valuable insights into the context and history of books.

The Case for Books was published before the Google settlement last fall. One cannot help but consider the irony – the book cannot be updated to include the latest information from a post-court-ruling world. But the irony is fleeting. The Case for Books is a manual on how to think about books and reading; its value is not simply in information, but in its understanding of the history and act of reading. This is why electronic communication, for all its speed and flexibility, will not destroy printed books – what we seek from literature is not so much updatability as wisdom.

Further Reading: The Late Age of Print: Everyday Book Culture from Consumerism to Control and The Book: The Life Story of a Technology

*Photo courtesy Chocolate Geek.

Send A Letter To the Editors