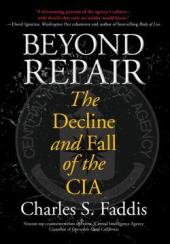

Beyond Repair: The Decline and Fall of the CIA

by Charles S. Faddis

—Reviewed by Adam Fleisher

How much safer would the world be if America could only find Osama bin Laden and infiltrate Al Qaeda, and figure out exactly what the North Koreans and Iranians are up to with their nuclear programs? Charles Faddis, a recently retired twenty year veteran of the CIA, thinks it’s not an impossible goal.

How much safer would the world be if America could only find Osama bin Laden and infiltrate Al Qaeda, and figure out exactly what the North Koreans and Iranians are up to with their nuclear programs? Charles Faddis, a recently retired twenty year veteran of the CIA, thinks it’s not an impossible goal.

In Beyond Repair, Faddis argues that American spies should be able to achieve these objectives and more once the broken and ossified CIA is replaced by a smaller, flatter, independent agency that functions less like a Washington bureaucracy and more like a think tank – with guns and spies.

The basic problem with the CIA today, Faddis says, is that it has gotten too big and too bureaucratic. Early in the Cold War it was a lean and aggressive organization. Over the decades, and especially since the end of the Cold War, the agency lost track of its core mission of collecting intelligence and running clandestine operations. As political oversight grew stricter after scandals like the Iran-Contra Affair, the agency became tentative and risk-averse.

Today, Faddis says, it fails to “encourage and reward risk taking, daring, and creativity” – attributes necessary to collect intelligence and run ground operations in hostile countries. The agency tolerates what it calls “intelligence gaps,” information deemed to be beyond the agency’s capacity to know. And though cultural change within the agency plays a part in this, Faddis acknowledges the increasing complexity of intelligence collection, the diversity of languages and cultures among our adversaries in the war on terror, and the inherent risks in trying to work with hostile people in hostile countries (as the recent attack on CIA offers in Afghanistan by a double agent demonstrates). He admits, too, that we do not want the CIA freelancing as it once did, but we do need it to collect intelligence well.

Beyond Repair might betray a frustration with the CIA, but Faddis certainly reveres his former employer. No other organization has the expertise, know-how and capacity to run a spy shop, he asserts. As bad as the CIA’s problems are, other government agencies like the Department of Defense setting up spy shops of their own is even worse, in Faddis’ view. The number of such agencies is now in the double digits; the perceived inability of the CIA to do it alone appears to have motivated their rise.

Still, Faddis insists that finding the right personnel to recruit spies and run complex secret intelligence-gathering missions requires careful recruiting and rigorous training – and only the CIA has the institutional capacity to do this type of work, buried somewhere beneath its bureaucratic layers. But each reform to date has only added more bureaucracy. “Committees and staffs,” writes Faddis, are “of no value in the conduct of human intelligence operations.”

Faddis’ solution is a radical one. He argues that we should simply “start over” with a new and improved agency that would focus on selecting and training effective leaders and would raise the standards – physical and mental – that deteriorated as the CIA moved away from on-the-ground intelligence collection. His envisioned agency wouldn’t hesitate to select agents from a broader group of people, including Americans who hail from other countries. It would also replace the other organizations that have become involved in foreign intelligence collection.

For all the disappointment with the CIA today, the author’s hostility to competing spy agencies is questionable. Granted, multiple agencies operating in the same space can create confusion, and efforts to cooperate and coordinate can make for turf wars or bureaucratic delays. But Faddis’ insistence that the military stay away from intelligence because it is too slow and lacks expertise is unconvincing. Many of the CIA’s recruits have military backgrounds, and the military has ably empowered special operations forces like the Green Berets and the Navy SEALs (maybe certain frustrated CIA agents could find a home in a similar espionage-driven special-forces team). And of course, given the sclerosis afflicting the CIA, perhaps a little competition wouldn’t hurt.

That is a mere quibble, however. Beyond Repair provides a succinct study of how an innovative and daring government agency devolved into a Washington bureaucracy. It remains to be seen if the agency can actually overcome established interests and start gathering intelligence all over again.

Excerpt: “Will a North Korean government at some point in the future threaten Japan with [nuclear] weapons? Will it threaten us with them once it has developed missiles capable of reaching the United States? Will it decide in retaliation for some perceived slight by the United States to make available an atomic weapon to a terrorist organization? I would submit that it is critical for the United States to have answers to these questions. Accepting that we do not know should not be an option. We should do whatever it takes and employ whatever methodology we need to employ to get this information.”

Further Reading: The Craft of Intelligence: America’s Legendary Spy Master on the Fundamentals of Intelligence Gathering for a Free World and Jawbreaker: The Attack on Bin Laden and Al-Qaeda: A Personal Account by the CIA’s Key Field Commander

Adam Fleisher is a law student at the University of Virginia.

*Photo courtesy Leo Reynolds.

Send A Letter To the Editors