Jonathan Alter, a senior editor at Newsweek and a native of Chicago, used his unmatched access to President Barack Obama to write The Promise: President Obama, Year One. Compiling the sometimes cutting, occasionally obscene anecdotes and asides of Obama’s inner circle, Alter reveals anew the much-watched administration. Below, Alter, a past Zócalo guest, analyzes Obama’s temperament, and how the president might benefit from adapting some of the style of Franklin Roosevelt and Ronald Reagan.

In March 1933, only a few days after he was sworn in as president, Franklin D. Roosevelt went to Georgetown to celebrate the 92nd birthday of retired Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. The small group of revelers enjoyed a little bootleg champagne as the old jurist advised the new president, “Form your battalion and fight.” After FDR left, Holmes rendered a judgment that was seen as capturing Roosevelt: “A second-class intellect but a first-class temperament.”

In March 1933, only a few days after he was sworn in as president, Franklin D. Roosevelt went to Georgetown to celebrate the 92nd birthday of retired Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. The small group of revelers enjoyed a little bootleg champagne as the old jurist advised the new president, “Form your battalion and fight.” After FDR left, Holmes rendered a judgment that was seen as capturing Roosevelt: “A second-class intellect but a first-class temperament.”

Barack Obama came to office with both a first-class intellect and a first-class temperament. Even his fiercest critics in Congress didn’t try to deny that he was smart and had an easy rapport with people he met personally. The question for him was about his public temperament – the way his character and style connected to the American people. Temperament is the “great separator,” as the legendary political scientist Richard Neustadt put it. “Experience will leave its mark on expertise; so will a man’s ambition for himself and his constituents. But something like that ‘first-rate’ temperament is what turns know-how and desire into his personal account.” In an age when the public gets to “know” the president so intimately through the media those with temperaments that don’t wear well – Herbert Hoover, Jimmy Carter, George W. Bush – have a harder time when things go badly.

A fine temperament is not the same as a winning personality; it denotes a particular mixture of ease, poise, and good cheer. That combination is necessary for great success in the presidency, but it’s not sufficient. The office offers even the most temperamentally well-suited person a hundred ways to fail. All that Obama’s easygoing temperament could do was improve his odds of handling the ongoing challenges and unpredictable events that would determine his fate.

Temperaments come in different shades. Lincoln’s was funny and wise, with a melancholy streak; he made other people feel good with his earthy stories. FDR’s was airy and effervescent; Winston Churchill compared meeting him to “opening a bottle of champagne.” Kennedy’s was bad-boy ironic and Reagan’s congenial with a theatrical touch. Clinton’s was protean, by turns explosive, impulsive, wonky, folksy. Bush senior had a country club affability and his son a fraternity rush chairman’s charm.

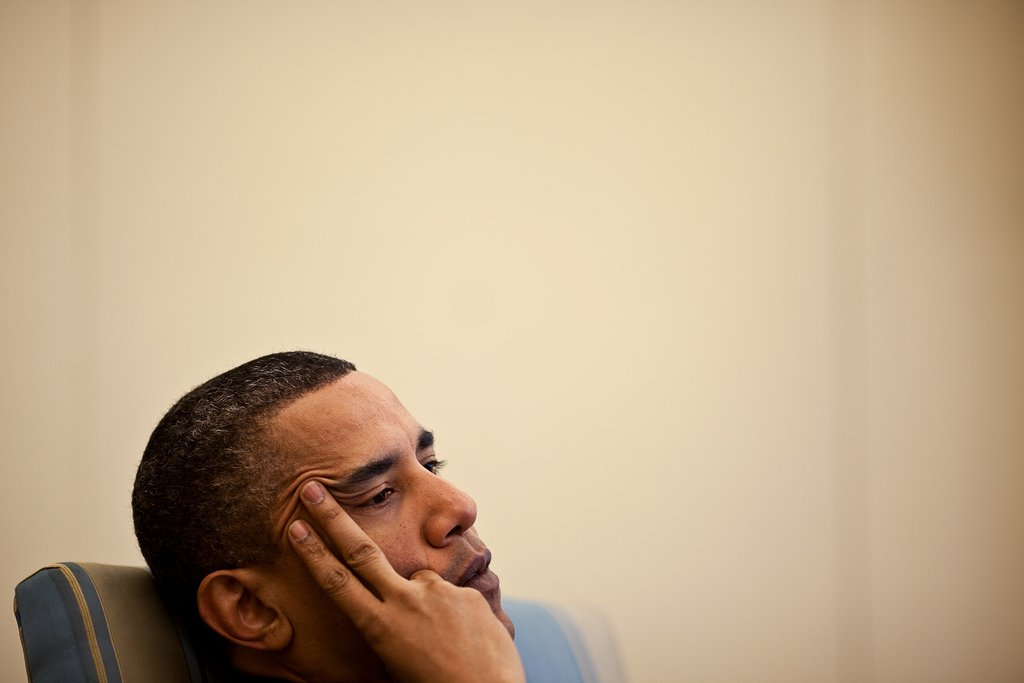

Obama wasn’t ebullient or a memorable raconteur. His cool, wry temperament – his moods famously never seemed to go too high or too low – could be perplexing. It had a mellow yet restless cast, a peculiar mix of calm, confidence, and curiosity. If the effect could sometimes be too professorial and disconnected from human hurt, the package was nonetheless impressive. With his high-wattage smile, elegant carriage, and a commanding baritone that could make his most ordinary utterances sound profound, Obama inhabited the role of president. Soon enough, his graying hair would add another touch of seriousness to a man who looked even younger than 47 when he took office.

It was this very seriousness that stood between him and certain elements of the American middle class that felt he didn’t fully connect with them. ironically, that gibe had arisen early in his political career when some black Chicagoans found Obama too “bourgeois” for their tastes – too middle-class. Rev. Jeremiah Wright’s Trinity United Church was dedicated in its founding documents to rejecting “middle-class values” in favor of authentically African American ones. (This was partly a pose; a large percentage of the congregation was black middle-class.) By the time he won the nomination for the U.S. Senate in 2004, the perception of Obama as temperamentally diffident and detached from the real concerns of African Americans gave way to great pride. Many white liberals in Illinois, meanwhile, supported him in part because of his race; voting for him was an affirmation of themselves and their own open-mindedness. The same coalition powered him through the 2008 Democratic primaries.

But the rap that Obama lacked a common touch reappeared in that campaign. The only reason Hillary Clinton hung on so long in the primaries was Obama’s weakness among white working-class voters who resented not just his claim that they were “bitter” and “clinging to guns and religion” but the whole Obama package. The attitude of these white voters was sometimes tinged with racism but had more to do with class anxieties. Obama was so obviously intelligent and well-spoken that he reminded them that a class of well-educated elites had left them behind. The Obama campaign worried that this vulnerability would hurt him in the November election, but the candidate deployed kitchen table issues (though he could never bring himself to call them that) and the financial crisis put a premium on brains and calm competence, which trumped class resentment. In any temperament contest with hotheaded John McCain, Obama won in a landslide.

With Obama, it was all about equipoise. “If I had to use one word to describe his temperament it would be ‘consistent’,” Axelrod said. “He’s a tremendously centered personality.” The calm had a paradoxical cast. “He has great self-assurance without being egotistical and he’s totally Zen-like without being arrogant,” said John Podesta. “it’s a very odd combination.” The only other people so relaxed and intense at the same time are certain professional athletes.

Obama’s temperament was also unusual because it was linked to his intellect. The two are normally more separate dimensions of personality, as Holmes’s line about FDR suggests. Some Americans found Obama pedantic. But most of the time his refusal to be conspicuous about his superior intelligence lent modesty to what might otherwise have been an impression of cockiness. Pete Rouse said that in thirty years on Capitol Hill he had never seen anyone with more faith in himself. And the only one he had seen anywhere close to Obama in pure intellect was Maine Senator George Mitchell, a former federal judge. What separated Obama from other smart senators, Rouse concluded, was that he was so confident he didn’t need to show it.

Obama’s disciplined insistence on giving rationality and open-mindedness pride of place kept him from being swept away by emotional currents. A bemusement about the phoniness of politics and the bloated egos it produces – plus a hardheaded wife – protected him from hubris, at least for now. And like FDR and Reagan (who patterned his style on Roosevelt’s), Obama’s winning smile obscured a layer of self-protective ice, a useful combination in a chief executive.

The tricky part was calibrating his detachment. Standing slightly apart from the action offered perspective and insulated him from the partisan clatter; standing above renewed charges that he lacked the human touch. Axelrod and other aides paid attention to this difficult balance but not enough. Already vulnerable with white middle-class voters, Obama needed to spend more of his first year compensating with emotional connections to the lives of workers and small business people. Once in the White House, Obama didn’t seem to grasp the psychological point that logic can convince but only emotion can motivate.

Part of this was a matter of public style. FDR and Reagan were better actors, an asset of special importance in the theater of the presidency. Obama won a Grammy Award for the audio version of his book Dreams from My Father. He could lovingly mimic even the female voices in his family saga and slipped easily into the accents of the black church. But his act was based on its never looking like an act. He knew that with one false and showy move he could crack the foundation of trust on which his public persona rested. “The core is authenticity and realness,” said his friend Marty Nesbitt. And so he resisted role-playing, which was commendable but limited his options.

As did his pride in his probity. He was properly insistent on separating friendship from business, but he lacked (and was proud to lack) Roosevelt’s manipulative streak, which he used during the New Deal and World War II to deceive people on occasion and play his advisors off one another. This might have made Obama a more admirable person than FDR, but it gave him one less tool for governing.

Excerpted from The Promise by Jonathan Alter. Copyright (c) 2010 by Jonathan Alter. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

*Photo above and on homepage courtesy The White House.

Send A Letter To the Editors