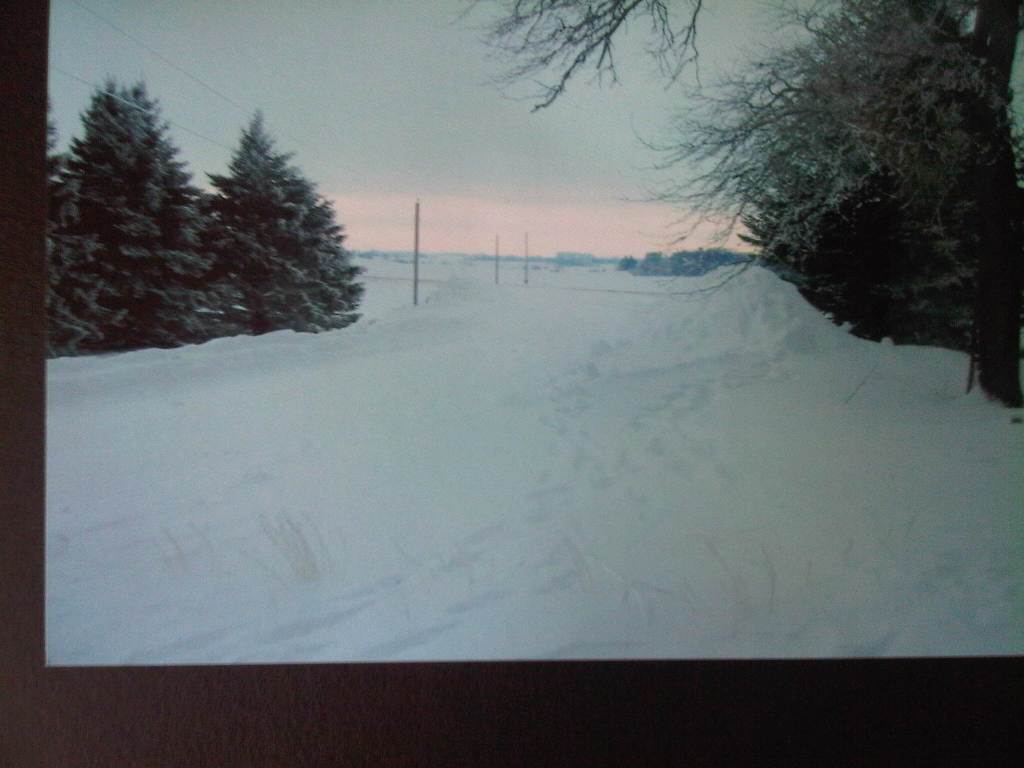

The southern Minnesota farmhouse, my childhood home, hides inelegantly behind a spotty row of evergreens. The trees stand bravely in the wind, the house’s only defense from winter’s bitter gusts. Outside the house’s curtilage lies a frozen expanse that, in warmer months, reveals fertile soil, a place where soybeans and corn flourish. But in November, at Thanksgiving, a bitter frost suffocates the earth.

It was in the farmhouse that I sat at midnight, alone, at the kitchen table, with a cup of tea and one of my favorite childhood books, Louis Sachar’s Wayside School is Falling Down, unopened in my grasp. At that moment – a rarity, if not functional impossibility – I had escaped the din of life. The follicles in my ears stood at rapt attention, trying mightily to search for the quietest of noises. But there were none. Everyone and everything slept. The frost kept critters at bay, and even the wind decided to rest for the night. Only my heartbeat stood between pure, unadulterated silence.

A slow sigh escaped my lips. Not a sigh of regret or exasperation or negativity. Just – contentment. I had made the long, difficult trip, trying to get away from my rowdy, peripatetic life. My future legal career is in Los Angeles. My friends are in Chicago. My Dad’s family lives in St. Paul. My Mom’s family resides in the farmhouse. My life is almost always a constant din, a racket both literal and figurative – from the unwavering traffic outside my downtown Los Angeles apartment to the constant voice in my head pushing me to achieve certain goals in my last year at law school. Getting away for Thanksgiving – or for any holiday – always presents an opportunity to escape the noise.

But it was not easy.

Traveling proved to be a loud logistical nightmare, starting with the flight: long security lines; new X-ray technology that broadcasts intimate details to airport security; travelers nervously glancing at their watches; constant messages blasting over the loudspeaker (“The moving walkway is ending!”). Passengers, in an attempt to avoid fees, shuffled aboard with bulbous bags only to find the overhead compartments full. The plane’s engines droned incessantly; what felt like days-old recycled air blasted from above.

The perils of travel, and the constant whirl of sound, were hardly limited to the airport. On this particular Thanksgiving, my circuitous route brought me from Los Angeles to Chicago for 36 hours, to my Dad’s house in St. Paul for a couple of days, and finally to the farmhouse in Owatonna, Minnesota, 80 miles from my Dad’s house. Along the way I connected with bits of my past. Chicago was a blur: seeing old friends, meeting new ones, eating Gino’s East pizza, watching a football game at Wrigley Field, laughing, yelling, cavorting. St. Paul involved my Dad, traffic, a Timberwolves game, and a movie.

It wasn’t until I reached Owatonna that I complete my journey to the place where I first began to find my identity. Of course, even traversing the 80 miles from St. Paul to Owatonna proved difficult. Freezing rain peppered the freeway and swirling gusts pushed my car from side to side. The wind howled through the imperfect window seals. Even here, in my car on a desolate Minnesota highway, 3,000 miles away from the fracas of downtown Los Angeles, noise permeated my world.

I finally made it. But the ever-elusive quiet would have to wait. My twin brothers, 12-year-old 6th graders, demanded my attention for most of the day. My Mom wanted to catch up for hours. After a loud but gratifying day of video games, football, wrestling, and talking, I was spent and the rest of the house was fast asleep. I was alone. It was then that I sat down at the kitchen table with my cup of tea and Wayside School is Falling Down. That book, which I first read in grade school and have read countless times since, first introduced me through its series of eccentric parables to the notion of individuality and the conflicts it can create. I didn’t need to read it again – its weight in my hand was nostalgic enough. Instead I silently reflected on my trip.

The concept of home, like the quiet we all seek, is often obscured and difficult to find. Is home where you grew up? Where your family now lives? Where your friends are? Where your career is? As I sat at the table, a hardcover memory still unopened yet firmly in my grasp, I knew I was home. I realized it was not my physical presence in the house but the culmination of the connections I made during my journey, and the chance to reflect in the enveloping silence, that made the experience so rich.

Send A Letter To the Editors