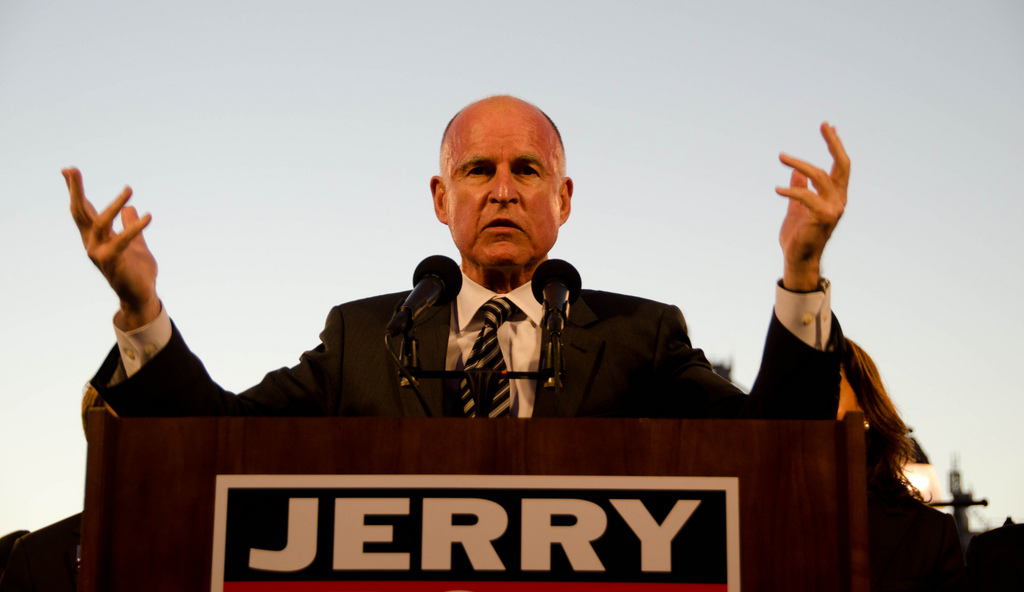

After surveying the state’s education and budget problems during a meeting with local education officials in Los Angeles last month, Jerry Brown joked: “I feel kind of like Rip van Winkle coming back here after 28 years.”

The crowd laughed, a bit uneasily. For the quip begged the question that many Californians are asking: Is Brown the same man who took office in 1975, at age 36, and served until the end of 1982? Or did his not-exactly-Winkleian sleep – a period that saw him run for president and serve two terms as Oakland mayor and one as state attorney general – change him for the better?

It’s a hard question to answer, because the first Brown governorship was a hard-to-describe combination of promising and maddening. To the good, Brown ran as a man more focused on ideas than on old-school politics and program building – a refreshingly frugal and fresh voice of a new generation. (He was 36 when he took office.) In some ways, he delivered. He made historic diverse appointments to California’s almost exclusively white-male judicial and executive branches. He pushed for development of alternative energies such as solar and wind power, long before it was cool. He won collective-bargaining rights for farm workers.

To the bad, Brown’s visionary nature and political ambitions meant that he had little time for the dull but important duties of a governor. “Our long suit has always been ideas,” his then-Chief of Staff Gray Davis confessed to The Washington Post in 1979. “Our shortcomings have been in staffing and carrying out those ideas.” He delivered on his promises of frugality – infrastructure funding and schools saw cuts, but the lasting impression was of a governor who was distracted and unfocused. Brown ran for president twice during campaigns that kept him out of the state for long stretches. And he was slow to respond to the 1970s tax revolt, a failure that contributed to the passage of Proposition 13, which has been a problem for state and local governance ever since.

For years, Brown’s political opponents have noted that Brown left office in the middle of a recession with the state facing a big budget deficit. But at this moment, the fact that Brown was present at the creation of some of California’s structural budget problems seems like highly relevant experience.

Still, the history of American retreads, as a political and cultural matter, is not a good one. Yes, the Coen brothers’ new “True Grit” is probably better than the 1969 version. But most remakes don’t match up to the originals. Coach Joe Gibbs, who returned to coaching football’s Washington Redskins in 2004 after 12 years away from the job, couldn’t match his Super Bowl glory the second time around. In politics, Cecil Underwood, West Virginia’s governor from 1957 to 1961 and then again from 1997 to 2001, did such a poor job the second time that he was turned out of office. And the second term of Grover Cleveland, a Democrat who was the only president to serve non-consecutive terms, was such a political and economic disaster that multiple Republican landslides followed it.

Throughout last year’s gubernatorial campaign, Brown sought to reassure Californians he wasn’t the usual retread. His second gubernatorial go-round, he argued, would be better because he has changed, in three ways. First, he now has a greater understanding of the real-world impact of Sacramento policies, because of his time as Oakland mayor. He also claims he is more focused today, in large part because he got married for the first time, in 2005, at the age of 68. His wife, Anne Gust Brown, is a no-nonsense corporate lawyer and former executive of The Gap who ran his unexpectedly disciplined campaign – and is expected to remain his top advisor in the new administration. And finally, his age – he’ll turn 73 in April – means he won’t be distracted from his state duties by national ambition. (At one debate with Meg Whitman, he allowed that if he were younger, he probably would be running for president again).

Since his election in November, Brown has signaled that he will focus relentlessly on the sort of boring, difficult questions of budgeting and spending that he neglected the first time. The only two major public events of his transition were two long, mind-numbing summits on budget issues. Brown and his allies ran through dozens of charts and made downbeat presentations emphasizing there is no easy way out of the state’s fiscal crisis. Unlike his bombastic predecessor Arnold Schwarzenegger, who promised to fix the state’s budget problems once and for all, Brown has made no promises. And he thus enters office with manageably low public expectations.

Brown thus may be in a stronger personal and political position than he was 30 years ago. But his statements and recent meetings also offer evidence that he may not have changed enough, particularly on policy. While he is presenting himself as more of a task man – and less of an idea man than he did in the 1970s – he is still promoting the same notions of frugality as he did during his first governorship. But frugality has not worked well in California. Brown is preaching to a state that has been stunted by a couple generations of government frugality, at least when it comes to most core services. (Public employee salaries and benefits are another matter). Schwarzenegger was by any measure the most frugal governor in the history of California. Still, the budget is not balanced. And the state has struggled to provide adequate funding for education, health care and the prisons. But Brown is hinting he will make more painful cuts to some of the same programs he limited in the ’70s. The real question, as yet unaddressed by Brown, is how the state is going to find money to make the public investments needed to catch up with its growth. In the last 10 years, a period of relatively slow economic growth in the history of California, the state’s population grew by some 4 million people, or 10 percent.

Brown, in matters of management, also appears to be repeating himself, building a team of advisors that is remarkably small by current gubernatorial standards. Some of the early appointees served him 30 years ago. If the new Brown administration were a movie, it would be shaping up as the California government version of “Space Cowboys,” the Clint Eastwood flick about retired astronauts who come back to save a failing satellite.

Those who are optimistic about the Brown administration counsel patience. They say that while Brown is moving slowly, he is moving. The optimists make much of the once and future governor’s vague talk about doing something – he hasn’t said what exactly – to reverse the post-Prop 13 centralization of fiscal and political power in Sacramento. “There will be some serious efforts to bring governmental activities, wherever possible, closer to the people,” Brown promised during his education meeting in L.A. If Brown is bold here, decentralization could offer a path to fix California’s badly broken system of government.

There is reason to doubt that he will ever get that bold. His two public budget meetings during the transition were jarring precisely because Brown didn’t bother to define success. He offered no clear goal for the budget’s size or for the quality or cost of state government. Brown talked mostly about the need to talk more and to find consensus – and about the fact that many budget balancing attempts had been self-defeating. In this, he sounded not unlike the Gov. Brown who, in 1975, lectured reporters on the virtues of inaction: “You don’t have to do things. Maybe by avoiding doing things you accomplish quite a lot.”

Whether this amounts to Zen wisdom – or is signs of a crippling fatalism – remains to be seen. In the most promising case, Brown will marry the visionary best of his idea-heavy first governorship with the more focused, detail-oriented governorship he’s now pledging, all in service of broad reform of California’s governing system. But that may be too much to ask of anyone, much less a man who has been away from the governor’s office for 28 years. California may be too broken to benefit from the older, wiser Jerry Brown. Even Brown seems to be aware of that.

“I’ve been around long enough to remember a different era when things were simpler,” Brown told his meeting. Then he added: “I don’t know how we get there.”

Joe Mathews, a fourth-generation Californian and a Zócalo contributing editor, writes about his home state and its politics, media, labor, and real estate. He is co-author, with Mark Paul, of California Crackup: How Reform Broke the Golden State and How We Can Fix It.

Send A Letter To the Editors