Pleasure Bound: Victorian Sex Rebels and the New Eroticism

By Deborah Lutz

—Reviewed by Catherine E. Bailey

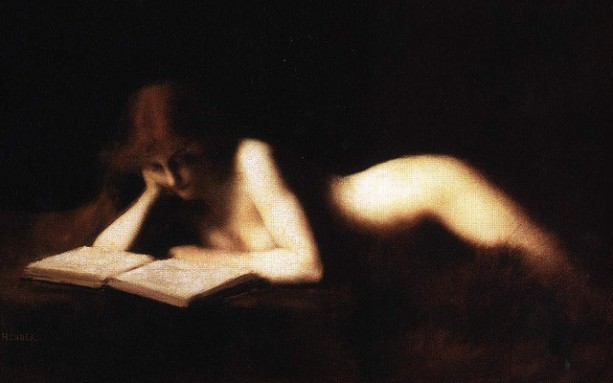

Nineteenth century England was a hotbed of social change and intellectual discourse. Charles Darwin presented his Origin of Species, Charles Lyell demonstrated the deep antiquity of the planet and mechanized factories transformed the workforce, polluted the Thames, and spewed out dark clouds that hung low over the city of London. Swimming in this sea of uncertainty, many mid-century Victorian artists and writers actively rebelled against the established mores of the day, creating works of art, literature and poetry that sought to pull the sexual and political fringe a few steps closer to the center. In Pleasure Bound: Victorian Sex Rebels and the New Eroticism, Deborah Lutz displays an uncensored view of London through the eyes of this decidedly uninhibited set of Victorian artists and free-thinkers as they sowed the seeds of a sexual revolution that continues to resonate today.

Lutz brings us into the fold of several intellectual clubs or salons where these thinkers gathered to glean creative inspiration and to hash out the controversial topics of the day. Two of the most prominent were the Aesthetes and the Cannibal Club. Membership of the two groups included significant overlaps and included the eminent explorer Richard Burton, a number of pre-Raphaelites like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, the early Impressionist painter James Whistler and the erotic poet Algernon Swinburne, among others. The members were embroiled in each another’s personal as well as creative lives, and sparks often flew over dinner discussions that ranged from art and literature to anthropology and pornography on any given night.

Pleasure Bound quickly corrects any misconceptions readers may harbor of a chaste and proper Victorian London with a damning historical mosaic of racy memoirs, personal letters, and journalistic articles detailing the city’s flourishing sex trade. Victorian officials of the upper crust were keen to maintain a patina of respectability, however, and actively sought to stamp out any public displays of vice by enacting various obscenity laws. Many of the Cannibals and Aesthetes (and their publishers) found themselves walking the line between pushing social boundaries and running afoul of the law and polite society. This proved a dangerous road to travel. Overdose, death, defamation and legal prosecution stalked individual members, claiming the lives and reputations of the unlucky. Most, however, learned to dance just out of reach of their vices and the law.

Lutz writes that she was drawn to the stories from the middle of the 19th century in part because they echo our own post-modern ideas about fluid sexuality. By the mid-1800s, nobody had yet demarcated sexual preferences into distinct types, leaving virtually infinite space for self-exploration. The word homosexuality, for instance, did not enter the English lexicon until 1891. Consequently, a strong sense of sexual ambiguity pervades the lives and works of the intellectuals discussed in Pleasure Bound such that they come across as light years ahead of their time. As we continue to struggle with our own collection of 21st century hang-ups over sexual rights and identity, this provocative set of Victorian voices sound startlingly familiar and suggest that, for all our scientific and legal wrangling in the intervening century and a half, we may have ended up right back where they started from.

Excerpt: Burton had been spoiling for just such a fight. In advance, he hired Sir George Lewis, a solicitor who was an expert in obscenity laws. “I don’t care a button about being prosecuted,” he fulminated to his wife, “and if the matter comes to a fight, I will walk into court with my Bible and my Shakespeare and my Rabelais under my arm, and prove to them that, before they condemn me, they must cut half of them out and not allow them to be circulated to the public.” Swinburne had used similar arguments to fight the censors of his work, pointing to Sappho’s place, for instance, in the classical education of boys in the best schools.

Buy the book: Skylight Books, Powell’s, Amazon

Catherine Bailey is a trained anthropologist and archaeologist. She currently works as a freelance writer and teacher in Los Angeles.

*Photo courtesy of uppityrib.

Send A Letter To the Editors