The NAACP has been at the forefront of the struggle for equal rights since its inception in 1909. But the symbolic significance of electing our first black president, the shifting attitudes toward race, as well as the nation’s new demographic landscape have triggered a reexamination of the movement’s priorities and goals. In advance of former NAACP chairman Julian Bond‘s visit to Zócalo, we asked four experts what role the historic organization should play going forward.

It’s Still Visible and Important, But Needs a New Plan

The NAACP–the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People–is the most important organization in African-American politics, and historically it was the most visible organization in the 20th century struggle for freedom and equality.

In the post-civil rights era, the NAACP, like the other major civil rights organizations, has found it difficult to adapt organizationally and programmatically to the new barriers associated with institutional racism and the so-called black underclass. Indeed, there was a scholarly consensus at the end of the 20th century that the NAACP in its organizational structure, programs, and strategies was out of touch with the complex situation of racialized poverty and the multifaceted problem of institutional racism. Such criticism of the NAACP is not new. As the most recognized and visible African-American political organization, the organization’s relevance and effectiveness has always been questioned.

The problem of the association’s relevance today is related to its continued adherence to liberalism in an era when the ideology is in decline; its continued reliance for financial support on white philanthropy; its continued tendency to focus on symbolic issues of concern to middle-class blacks; and its reliance on traditional lobbying and litigation strategies that do little to address the problems of poverty and the “underclass”.

While the association has a large number of branches (estimated at more than 1500), its membership at the end of the 20th century was only about 200,000, considerably less than the estimated 400,000 in the 1940s although the black population has more than doubled since then (from 14 million to more than 35 million). The 1500 vary in size and activity, and tend to be dominated by an elderly membership. (It is estimated that two-thirds or more of the active members are 60 or older).

The NAACP has always had trouble attracting young people. In 1936, over the initial objections of the executive director, the association established a youth council and began to charter youth councils and college chapters. But in the 1960s, young people, dissatisfied with the NAACP’s middle class status and conservative approach, tended to drift toward other groups. In the post-civil rights era, this problem continues despite the promises of the organization’s leaders to involve young people in the group’s membership and leadership. J. Wyatt Mondesire, the former head of the 14,000 member Philadelphia branch, remarked in a 2001 interview that the situation was so bad with young people that “when I go out and speak to kids on college campuses and high schools, and I ask them what NAACP stands for, a lot of them think that I am talking about NCAA [the National Collegiate Athletic Association]. That’s how pitiful it is.”

Despite this, the NAACP remains the most important political organization in black America and one of the largest grassroots organizations in the United States. In most cities and towns, the local chapters are generally recognized as a dominant voice on black affairs, and they are usually consulted by white economic and political elites seeking advice on issues related to race. These chapters represent a potentially powerful social and political force that could be mobilized if the association could develop a national strategic program and plan of action to address today’s multifaceted problems of poverty and institutional racism.

The question, therefore, is: Can the NAACP–given its history, ideology, and organizational ethos–develop and implement such a plan and program? Can it adapt to the challenges of the 21st century and remain the most important organization in black politics? Or is it likely to remain an organization with a glorious past and an irrelevant future?

Robert C. Smith is a professor of political science at San Francisco State University. He most recently authored Conservatism and Racism and Why in America They Are the Same.

—————————————————————————————————————

The Fight for Racial Equality Isn’t Over

The NAACP is as relevant and needed today as it was 50 years ago. Racism has diminished in the years since the Civil Rights laws of the 1960s were enacted. Overt racists are increasingly a minority of America’s population, but we do not live in a post-racial society. Today, most whites believe that they support racial equality, but many of them harbor unconscious stereotypes and attitudes that social scientists have labeled “racial resentment.” This condition is an intense, emotional opposition to policies designed to assist racial minorities. Racial resentment is different from traditional prejudice because it is not based on a belief that African-Americans are biologically inferior. This psychological disposition is not usually conscious; it tends to reside deep within an individual’s psyche.

Internalized stereotypes cause many whites to harbor negative attitudes about African-Americans without a conscious awareness of the source. Whites can act in ways that disadvantage minorities as long as they can rationalize a race neutral justification for their actions. This can affect decision-making across a broad range of activities–including hiring, promotions, home buying (black buyers are taken to some neighborhoods but not others), and decisions on arrests and prosecution.

One of the most significant impediments to black progress is the persistent discrimination in the nation’s housing markets. A study using census data from 2005-2009 determined that progress in housing integration came to a halt during the first decade of the twenty-first century. African-Americans are the most segregated minority, followed by Hispanics and Asians.

This is not a matter of the private choices of individual families. Researchers have shown that, in rental and sales markets in metropolitan areas nationwide, black and Hispanic home seekers experienced significant levels of adverse treatment, compared to similarly situated white home seekers. This affects living conditions and the quality of public schools in black neighborhoods.

If the current trends continue, the black middle-class will continue to grow. Some blacks will achieve socioeconomic parity with their white counterparts, but most others will continue to lag behind. The NAACP and organizations like it are still needed to advocate for racial equality.

Leland Ware is a Louis L. Redding Chair and professor of Law & Public Policy at the University of Delaware. His research and professional interests include civil rights law, employment law.

—————————————————————————————————————

It Faces New Challenges, But Must Uphold The Same Mission

Throughout its history, the NAACP has upheld civil rights for ethnic minorities, working for political, educational, social and economic advancement. Some of the issues have changed over time, yet many are still strikingly similar. Where the NAACP once sought Depression-era economic justice, it now combats modern-day economic inequities. Where it once advanced school desegregation, it now fights school re-segregation without an individual or state actor to always blame. Voting rights have been won, yet we see retrenchment by the court.

Key challenges in today’s society take a more-subtle form: structural inequities, growing racial anxiety, and implicit bias:

- Structural barriers–in areas ranging from education and housing to employment and health care–limit access to opportunity.

- While some racial gaps have been bridged, Americans still harbor deep racial anxieties triggered by globalization and a declining middle class. This fuels anti-immigrant sentiments and raises fears of a declining white majority.

- Overt racial discrimination is obsolete, yet Americans still subconsciously hold “implicit” racial biases as an outgrowth of our troubled racial past. These hidden biases preserve discrimination in forms such as racial profiling and inequities in criminal sentencing.

In this current landscape, the challenges are new but the mission is still the same. Now, as always, the NAACP continues to lead the charge to uphold racial equity and like its founder, continues to raise understanding of the relationship between different domains such as economies, civil rights and global dynamics.

John A. Powell is executive director of the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity and Gregory H. Williams Chair in Civil Rights & Civil Liberties at The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law.

—————————————————————————————————————

It Protects Rights for All

In many ways, the NAACP stands for the same thing it has always stood for–advocacy for the equality of rights of all persons.

Despite the oft-misunderstood NAACP nomenclature and acronym, the fact has always been that the NAACP fought hard for the equality of rights of those who needed it most. For many years, those were primarily African Americans, and, of course, that challenge still remains. However, there are also other groups intersecting the traditional advocacy group on whose behalf the NAACP has long labored. Among those are members of the LGBT community, members of religious minority groups, and lower income persons of all ethnic backgrounds.

The nation’s oldest civil rights organization has been right to maintain its traditional roots while adapting to the new challenges of the twenty-first century. I’m proud of the fact that the NAACP has been and continues to be on the right side of history. And, I’m confident that the NAACP will be on the side of millions of American citizens and their allies who face daily the many challenges of modern era civil rights battles. If the NAACP did not do so, the organization would not be living up to its own mission. And the mission–equality of rights for all, wherein all means everybody–is what the NAACP stands for, both back then, today, and tomorrow.

Dr. Ravi K. Perry is assistant professor of political science at Clark University. He is currently writing Black Mayors, White Cities, a book manuscript on the challenges Black mayors face in representing Black interests in majority white, medium-sized cities.

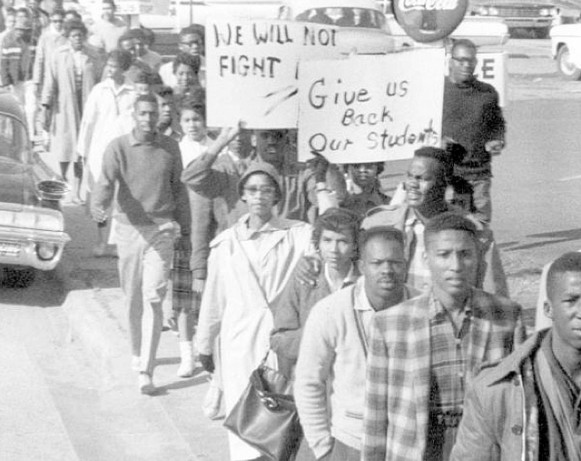

*Photo courtesy of Village Square.