As an inventor, I place a lot of weight on understanding the words I use to describe the problem I am addressing. For example, in medicine, the word patient is from the Latin patiens, meaning to suffer or long endure. It’s a word with both social and moral implications, and it reflects our fundamental approach to medicine: we wait until you have a complaint, and then we try to treat it.

Still, everyone agrees that it’d be better if medicine prevented the illness in the first place, or at least detected it early, before there were any symptoms. With almost any disease, the earlier you find it, the better your chances of getting well.

Still, everyone agrees that it’d be better if medicine prevented the illness in the first place, or at least detected it early, before there were any symptoms. With almost any disease, the earlier you find it, the better your chances of getting well.

Unfortunately, early detection, at least as we currently know it, comes with two big problems. The first of those problems is that early test results are often wrong, leading to what we call “false positives.” When you diagnose someone with a serious disease, you’re also advising that person to take a costly next step–maybe even to undergo a life-threatening procedure. And if you’re doing all of this to combat some imaginary threat, then you’re causing someone a lot of pointless mental anguish and endangerment. The second problem is that many diseases still can’t be spotted early. Alzheimer’s, for example, becomes diagnosable only years after it sets in.

What we need to do, then, is to detect illness before there are symptoms–but get it right. And we don’t want to break the bank doing it either. Meeting these challenges is what I’m working on with my colleagues at the Center for Innovations in Medicine and at my company, HealthTell.

To transform our medical system from reactive to proactive, we’re going to need early detection methods that are very cheap, extremely accurate and nearly comprehensive in their ability to detect different diseases. That’s a very tall order–some would say an impossible order–but we may be on the cusp of something that meets those three criteria.

At our lab, we’re developing a new system called ImD, which stands for “immunosignaturing diagnosis.” Let me explain it simply. Each of us has about one billion different antibodies in our blood and saliva at any one time. (B-cells produce them in response to infections or bad cells.) The underlying idea of ImD is that the antibodies in your blood and saliva change when your health changes. Understand those changes and we understand the diagnosis.

What we’ve found is that a simple chip can be used to read those changes in these antibodies. (The chip has 10,000 short peptides on it.) Each of us has our own personal, core immunosignature, but this signature changes when a disease develops. If you are developing a certain disease, your immunosignature will start to overlap with the immunosignatures of other people developing the same disease. That allows us to detect something very, very early in the game. And using these chips (which HealthTell is involved in producing) to read immunosignatures has proven successful for every disease we have tested to date.

ImD is pretty easy for the patient. Just put a drop of your blood or saliva on a filter paper and send it to the lab in the mail in a standard envelope. The antibodies are very stable. In the lab, technicians will apply the antibodies to the chip and see what they find.

In an era in which primary care physicians are in way too short supply, ImD technology could become an important part of our medical future.

Imagine–just once a week or month you put a drop of blood or saliva on a filter and drop the envelope in the mail. A few days later you go to your health site on the computer and it tells you if there is any change in your immunosignature. No change? Then you’re fine. Otherwise, see a specialist.

This would represent a huge cultural shift in our healthcare system. People, rather than the medical community, would “own” their medical data. Individuals would decide for themselves how much to involve medical doctors in analysis or treatment.

Such a change would open up many challenges, of course, and it would raise many of the same kinds of concerns that we saw expressed during the Internet revolution. When everyone suddenly has access to vast quantities of information, people are understandably wary of the power of technology to bring change that’s not entirely welcome.

But technology such as this has great potential to make our lives better and longer. And it goes beyond just detecting disease. For example, it could also be used as feedback by people who want to live healthier lifestyles–effectively allowing them to track their progress.

Would this lead to a revolution on the scale of the Internet? Perhaps not, but it might be close. It’s hard to imagine, but soon we could have a world of medicine in which people no longer need to be patients–or be patient.

Stephen Johnston is director for the Center for Innovations in Medicine, a professor in the School of Life Sciences, and director of the Biological Design Graduate Program at The Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University.

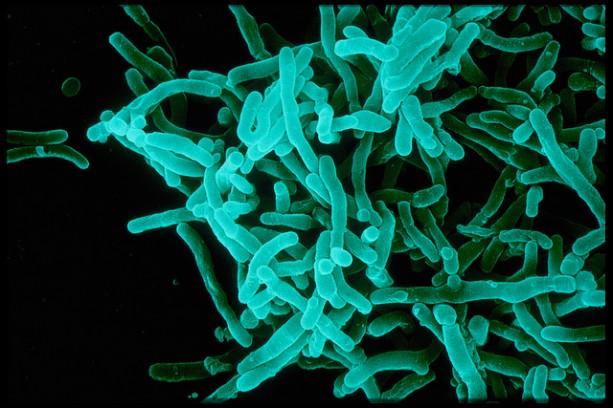

*Photo courtesy of Sanofi Pasteur.

Send A Letter To the Editors