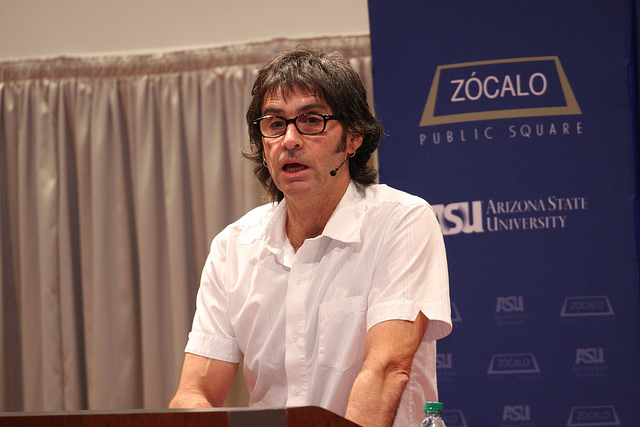

“If Phoenix can become sustainable, then it can be done anywhere,” declared writer and cultural analyst Andrew Ross. This was the inspiration behind his new book, Bird on Fire: Lessons from the World’s Least Sustainable City, which explores the past, present, and future of the green movement in the Phoenix area.

Ross was speaking at a Zócalo event co-sponsored by Arizona State University, and many members of the large and rapt audience at the city’s Heard Museum were among the 200 “influential and thoughtful citizens”–lawmakers and urban planners, artists and activists–Ross had interviewed as part of his research. They, and he, recognize that the challenges to greening Phoenix are many, but by no means is the city’s battle against climate change lost.

With an appetite for unrestrained growth, a disproportionate consumption of natural resources, an arid climate, poor air quality, and an economy hit hard by the housing bubble’s collapse, Phoenix “is in the bull’s-eye of climate change.” But it’s just one of many fast-growing cities around the world in semi-arid regions, and it may have more to teach us than showplace green urban centers like Portland, Reykjavik, or Curitiba (Brazil). These are the cities that dominate our national conversation about sustainability, said Ross, and yet there’s nothing sustainable about addressing only those areas that can afford it.

In Phoenix and other cities like it, a green gap–“eco-apartheid” is the term environmental activist Van Jones introduced–exists between green living oases and human and natural sacrifice zones “on the other side of the tracks.” Said Ross, “There is nothing really sustainable in the long run about one population living the green American dream, while across town another is trapped” in an entirely different reality, where clean water and air are hard to come by.

In Phoenix, green innovations like solar technologies, hybrid cars, and low-impact landscaping are marketed to the residents of its affluent northern regions. Meanwhile, poisoned groundwater flows beneath the city’s downtown–and eventually makes its way up into buildings above ground.

“How do we prevent these [affluent] areas from turning into eco-enclaves, hoarding resources and knowledge about sustainability from others?” asked Ross.

The answer lies not just in quantitative factors like per-capita water consumption and housing density, or in small technical and physical improvements, but rather in social cooperation and other qualitative measures of equitable sustainability for which simple metrics don’t exist.

One example is the capacity of cross-town communities to share water supplies. With the Southwest in the midst of a long drought, the cost of bringing more water to Phoenix is sure to escalate, and how well different neighborhoods share this resource with one another will be an important test of the area’s ability to adapt and adjust. The growth of solar power in Phoenix is another area of glaring inequity. Sun is the state’s most abundant natural resource, but less than 2 percent of its energy is solar-powered–in part because the Arizona state legislature has placed a regressive surcharge on installing solar roof panels that affects even renters, and hits the poorest the hardest. (State and federal governments, said Ross, are influenced much more by the fossil fuel lobby than city governments, which is one reason why cities are at the forefront of the green movement.)

Even immigration policy needs to become a part of Arizona and Phoenix’s conversation about sustainability. “Climate change doesn’t stop on the border,” said Ross. Many immigrants from northern Mexico, which is quickly drying out, are climate refugees who are being driven from their land and livelihood by diminishing resources. Arizona’s new policies are actually an example of resource hoarding, said Ross. This is going to be “the first real skirmish in the climate wars to come,” he argued. More and more, affluent nations or regions will become resource islands that maintain their own right to go on polluting at the expense of the rest of the world’s population.

Ending on a more optimistic note, Ross recounted the story of the Gila River Indian Community, whose largely undeveloped tribal lands stand directly in the growth path of the Sun Corridor mega-region. In the late 19th century, Anglo development cut the community off from the water resources it needed to survive. After a long war in the courts, a 2004 settlement gave them back their water rights, which they are going to use not to create more tract housing, but to restore as much as 150 acres of farmland that can produce healthier food for the entire area.

It’s an example that’s not easily replicated, but it’s a case of social and environmental sustainability successfully going hand in hand. “A green polity ought to redress the claims of those who have been aggrieved, and do it in a way that extends long-term benefits for everyone,” said Ross. “The green wave has to lift all vessels.”

By and large, the people of Phoenix Ross met and interviewed were optimistic about the city’s sustainable future; it was difficult for Ross to find an apocalyptic vision among them. He believes that it just might be possible for the city to become model for not only the Southwest, but for the rest of the world as well.

Ross concluded by invoking Jane Jacobs, who believed that urbanization is an open-ended process. If that’s the case, he said, “then the greening of cities like this one is a grand act of improvisation, maybe the last heroic effort in places like this where it can still make an appreciable difference.”

Watch full video here.

See more photos here.

Buy the book: Changing Hands, Skylight, Amazon, Powell’s.

Read expert opinions on whether cities like Phoenix can ever be made sustainable here.

*Photos by Felipe Ruiz Acosta.

Send A Letter To the Editors