Paris had its Montparnasse; New York City had its Greenwich Village. But what about Los Angeles? Actually, many artists, writers, and musicians decided the City of Angels was the most exciting place to be during the early years of the twentieth century, when a pervasive atmosphere of expectation and unrealized potential made the city quite unlike any other. Perhaps the seductive scent of California poppies coupled with the pungent odor of opportunity gave the zephyrs of Los Angeles an especially intoxicating quality.

In 1900, the population of Los Angeles was a mere 100,000 residents (on par with Toledo or Indianapolis or Denver, and only one-third the size of San Francisco). Over the next decade, a surge of new arrivals caused that number to triple. By 1920, the population had climbed to almost 600,000. Los Angeles offered a healthy climate, incomparably sunny skies, burgeoning employment opportunities, and, perhaps most important, the chance to reinvent oneself. At a time when Social Security numbers did not exist and news did not instantaneously travel from place to place, newcomers could change their names, concoct personal histories, and become whoever and whatever their talents and bravado would allow.

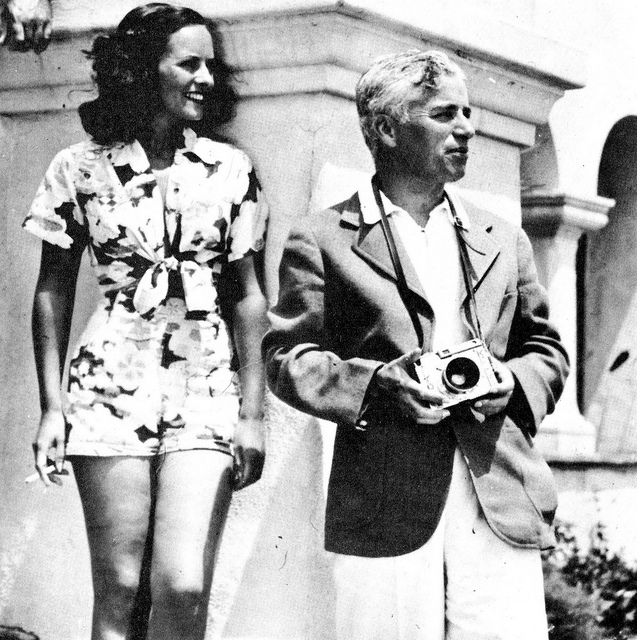

Many gravitated to accommodations in dilapidated Victorian-era boarding houses that populated the heights of downtown’s Bunker Hill; others to rustic bungalows strewn across the hillsides of nearby Echo Park and Silver Lake. Although these individuals lived hand-to-mouth and moment-to-moment, they pursued their dreams and enjoyed their lives. They became the bohemians of Los Angeles, living unusual and often artistic lives. They were people like bookseller Jake Zeitlin, artist Paul Landacre, architect Rudolf Schindler, author Raymond Chandler, photographers Edward Weston and Margrethe Mather, and actors Charlie Chaplin, Rudolph Valentino, and Boris Karloff. All resided within the city’s bohemian neighborhoods and often found themselves going down parallel (and occasionally intersecting) paths.

Visitors from other parts of America and the world also passed through Los Angeles regularly. Socialist Max Eastman and anarchist Emma Goldman paid many rabble-rousing visits. Carl Sandburg strummed a guitar and recited his poetry. Vaslav Nijinsky leapt to unprecedented heights with the Ballets Russes. Ruth St. Denis and her husband, Ted Shawn, founded a dance school near Westlake Park. Everyone who was anyone wanted to experience life in Southern California–at least for a few days.

The migration of the moving-picture industry to Los Angeles brought even more talents to the city. Men like Mack Sennett, Cecil B. DeMille, Samuel Goldfish (who soon became Goldwyn), and Jesse Lasky became the powerbrokers of Hollywood, turning vaudevillians into movie stars and bathing beauties into screen sirens. Even L. Frank Baum, author of the legendary Wizard of Oz books, migrated west from Chicago and built a spacious fairytale bungalow just north of Hollywood Boulevard. He called it Ozcot.

And then there was everyone else–the hundreds of fledgling actors, writers, artists, musicians, designers, directors, and cameramen who were enticed by the promise of fame and riches. Even though most never made it into the upper ranks, they nevertheless stayed, content with modest homes in the flats of Hollywood and an occasional night out at Victor Hugo’s restaurant downtown, topped off by a cocktail at Musso & Frank’s Grill on Hollywood Boulevard.

While the Los Angeles art world grew at a much slower pace than the newly established movie industry, the autumn of 1913 saw the opening of the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art (now the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County). With that artistic anchor in place, a handful of privately owned art galleries began to attract budding collectors. During the 1910s, artists received a warm reception from bookseller Ernest Dawson. During the 1920s, they often exhibited their work at Jake Zeitlin’s Sign of the Grasshopper bookshop or in the furniture and design studio of Cannell & Chaffin or in the galleries of the newly opened Bullocks Wilshire department store.

When the Great Depression of the 1930s arrived, many gallery owners reluctantly closed their doors, Stanley Rose and Howard Putzel (who would later become an adviser to Peggy Guggenheim) among them. World affairs in that decade became ever grimmer, culminating in war in Europe. The result was renewed turmoil in the American economy, and the art world went into a tailspin. In the late autumn of 1941, gallery owner Julien Levy, despairing of the New York art market, arrived in Los Angeles equipped with a “traveling road show” of paintings drawn from his inventory. He rented a storefront on the Sunset Strip and set up shop a few doors away from the Frank Perls Gallery, hoping to attract some prosperous new clients. A few days later he departed, sorely disappointed with his venture. When he arrived at New York’s Pennsylvania Station, loudspeakers were carrying news of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. War was now certain.

As conditions worsened in Europe, an influx of émigrés fleeing the Nazis came to Los Angeles, where they often gathered at the Villa Aurora, the Pacific Palisades home purchased in 1943 by novelist Lion Feuchtwanger and his wife Marta. Included in this group were author Thomas Mann, composer Arnold Schoenberg, playwright Bertolt Brecht, and novelist Franz Werfel and his wife Alma (the former spouse of both conductor Gustav Mahler and architect Walter Gropius). These luminaries brought with them a sophisticated sensibility that would influence the cultural landscape of Los Angeles. Another arrival was Brooklyn-born photographer Man Ray, recently of Paris, who settled into a Vine Street apartment.

Meanwhile, as local manufacturing industries proved essential to the success of the war effort, a steady infusion of federal and private money poured into the city, and a new cycle of growth began that would continue long after war’s end. This prosperity attracted a new surge of talent to Los Angeles, and it is this group and their achievements that are currently the subjects of an array of citywide exhibitions, collectively called Pacific Standard Time, which aim to celebrate the 1945 birth and subsequent maturation of the Los Angeles art scene.

Even as we celebrate the cultural achievements of post-war Los Angeles, however, we should remember those important decades of gestation early in the twentieth century, the decades that established the city’s reputation as a place where creative people were valued and artists of all persuasions could aspire to make a living doing what they loved. It was these individuals–the bohemians of Los Angeles–who first propelled the City of Angels into the limelight and who set the stage for the artists of Pacific Standard Time to make their own important contributions.

Beth Gates Warren is the author of Artful Lives: Edward Weston, Margrethe Mather, and the Bohemians of Los Angeles.

Buy the book: Amazon, Skylight, Powell’s

*Photo courtesy of classic film scans.

Send A Letter To the Editors