Reporters and gadflies worship the Brown Act, California’s open meeting law, except for their complaints that it isn’t stringent enough. Ironically, the mother of all state sunshine laws was drafted not by open government crusaders but by lawyers for the California League of Cities, which now routinely tries to fend off efforts to make the law even more onerous for the 5,000 counties, cities and public agencies that must abide by it or face civil and/or criminal penalties.

The Brown Act is in the news this month, via reports that the state government had gutted it. These accounts are not only wildly overblown, they miss the real story of the evolution of this landmark law in the nearly six decades since it was first passed.

The Brown Act is in the news this month, via reports that the state government had gutted it. These accounts are not only wildly overblown, they miss the real story of the evolution of this landmark law in the nearly six decades since it was first passed.

The original Brown Act legislation stemmed from a 10-part investigative series in the San Francisco Chronicle called “Your Secret Government.” The League of Cities embraced reform and persuaded Assemblyman Ralph M. Brown to introduce the bill, which was signed into law by Governor Earl Warren. Originally only 686 words when it went on the books in 1953, it still carries some of the original straightforward eloquence of a more innocent time:

The Legislature finds and declares that the public commissions, boards, and councils and the other public agencies in this State exist to aid in the conduct of the people’s business … The people of this State do not yield their sovereignty to the agencies which serve them. The people, in delegating authority, do not give their public servants the right to decide what is good for the people to know and what is not good for them to know … All meetings of the legislative body of a local agency shall be open and public.

The law has since become part of California’s civic DNA. Elected and appointed officials almost universally abide by it, some enthusiastically, others more grudgingly. What the act hasn’t done is prevent the worst abuses–because corrupt officials deliberately and secretly evade them. The Brown Act was no barrier for those who granted themselves bloated raises and pensions in Bell, to pick a brazen example. On balance, though, the Brown Act has undoubtedly made local government more open and transparent, if sometimes at the cost of accomplishing the people’s business at the local level.

That’s because the law now runs nearly 15,000 words of mind-numbing detail that no human being could possibly retain and still have brainpan left over to perform an actual job in government. And while the spirit of the law remains hugely beneficial, the letter of the law has also had plenty of unforeseen adverse consequences.

Among the amendments that have bloated the law to elephantine proportions were provisions to forbid legislative bodies from going on often expensive and effectively secretive “retreats.” The legitimate purpose of such gatherings (if there was one) was to focus on the thorny challenge that Rodney King famously posed: “Can we all get along?” Given diverse philosophies and personalities, all too many public bodies suffer dysfunction that can poison public business. What’s wrong with getting everyone away for a weekend to confront and defuse the thorny personal differences that can divide a Council and thwart effective governance?

Good riddance to that well-meaning idea when the Brown Act was altered to forbid boards from gathering outside the borders of their jurisdiction. The amendments were so onerous, however, that the California League of Cities was even forced to drop trainings aimed at promoting harmony among groups of city councils.

If you’ve ever sat through a City Council meeting where “colleagues” do every spiteful thing except heave dead cats at each other, you might long for the bad old days when “retreats” could be held at some reasonable remove to foster candor and preclude playing to the local crowd.

Such trade-offs pale in comparison to all the salutary benefits of sunshine on local government. But the current controversy over the Brown Act obscures the important distinctions between what’s essential about the act–and what isn’t, and thus could use fixing. As a starting point for a sensible discussion, Californians should understand the law has barely been touched and certainly not gutted, no matter what you read in the papers. In reality, our state legislature “suspended” part of the law (which doesn’t apply to them) to save $96 million in state reimbursements to local governments for the cost of posting meeting agendas outside City Halls up and down the state. Ironically, the obscure provision was tucked into a mammoth budget package and received no public scrutiny until after it was signed into law by Governor Jerry Brown (no relation to the act’s sponsor).

The specific provisions suspended by the Legislature for the next three years are relatively trivial. In today’s world, the most effective posting of meetings is on the Internet, which costs the State nothing, so that practice is unlikely to change at all. Another provision about disclosing the results of “closed sessions” (which are only allowed in exceptional situations) will also be iced, but that too is unlikely to actually cause many agencies to alter their practices. In fact, these same Brown Act requirements were suspended by the Legislature during the 1990 fiscal crisis with little impact on local compliance. Although this new “suspension” will change very little, the Brown Act’s symbolic power ensures impassioned rhetoric on the topic. There’s even a threat by a State Legislator to (wait for it) launch an initiative to enshrine all the complicated provisions of the Brown Act in the California State Constitution (already among the longest in the world after the constitutions of Alabama and the nation of India.)

But before we pass a proposition to cement every provision of the Brown Act into our Constitution, we might reflect on the wisdom of the ancient Athenians, the inventors of democracy. We “must know how to choose the mean and avoid the extremes on either side, as far as possible,” Plato quoted Socrates as saying, capturing the essence of the “Golden Mean” celebrated by the Greeks.

When it comes to the Brown Act, let us praise its authors and faithfully follow their intent, but let us be skeptical about whether “suspension” of some of its most inconsequential provisions constitutes an actual threat to our liberties.

Rick Cole is City Manager of Ventura. His views are his own.

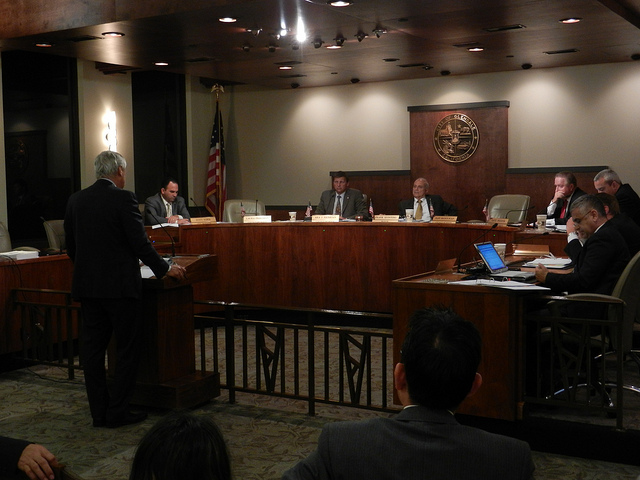

*Photo courtesy of scottjlowe.

Send A Letter To the Editors