I went to high school in Lincoln County, Georgia, during the dwindling days of Jim Crow. I didn’t understand all that was changing right in front of me. Elijah Clark State Park was for whites, and more distant Keg Creek State Park was for blacks. I don’t recall separate water fountains and restrooms, and the only bus I rode was a yellow schoolbus. No one cared who rode in the back. In fact, it was cool to ride in the back.

We had our Jim Crow moments, though. In the final photograph of the 1967 Panorama, a slim gold-and-black collection of public school photographs, stand two black janitors, with four black lunchroom women between them. You won’t see their names. Instead, you will find the following dismissive words: “These fill a vital role at L.H.S.”

In the world of Jim Crow rules, a white man did not shake hands with a black man, because it implied social equality. With rare exceptions, blacks and whites didn’t eat together (although I had many a meal in the 1960s with my black friends down on the farm), and if they did eat together, whites were to eat first. If a black person rode in a car driven by a white person, the black person sat in the back seat. Another rule: White motorists had the right-of-way at all intersections. Good God. Surely that was a formula for disaster!

It’s damn hard for me to believe all this. But it was real. Even black music was taboo. It used to be called “race music.” If the term sounds unfamiliar, that’s because Jerry Wexler of Billboard coined “rhythm and blues” to replace “race music” in 1948. (Although blacks referred to their music as race music, Wexler, who was Jewish and sensitive to the unintended impact of words, had found the original term derogatory.) But one group of kids did cross racial lines to listen to R&B: those were the “shaggers,” the original bad boys.

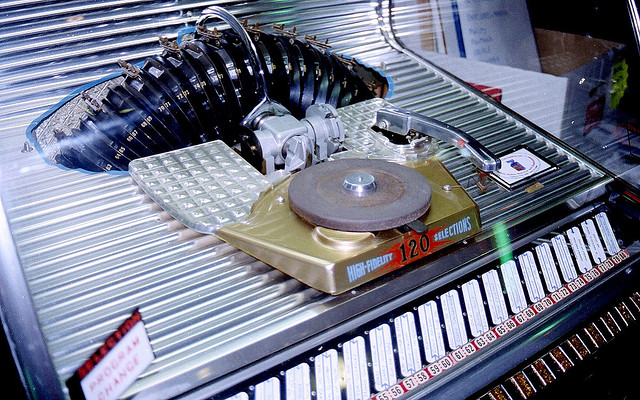

The shag is a slow, smooth couples dance that evolved out of the jitterbug and earlier dances. You can only dance the shag to beach music, which has roughly 120 beats a minute. Think of The Four Tops and The Platters. It’s hard to shag without a strong sense of seduction and romance. Few people beyond the shag world consider the first wave of shaggers to have been Civil Rights trailblazers. Well, they were. They had three confederates old timers will recall with affection: the jukebox, 45 RPMs, and that fabled music we know as the blues.

***

Some say it rolled off the Mississippi like a mist that mesmerized all who breathed it. Others say it shot up from the river’s alluvial plain, the Mississippi Delta. Something mystical, something melancholy came out of the delta all right—the blues, that sadly beautiful, beautifully sad music. And the blues, that mighty tributary of melody that grew out of work songs, spirituals, shouts, and chants, would forever change lives.

To understand how people fell in love with the blues, you have to understand the times that led to it. It was a time of taboos, a time when danger accompanied things we take for granted today. It was a time when parents didn’t approve of race music or the dancing and its settings. It was a time that called for doing the unacceptable.

Jim Crow governed music too. In a bit of reverse discrimination, whites could not enter black clubs and watch black performers. Nor could black entertainers perform in white establishments. Thus it was that unknown-but-stardom-bound blacks performed on the Chitlin’ Circuit, a string of clubs throughout the South where they could do their thing in a safe, acceptable venue.

Charlie’s Place was a club on the Chitlin’ Circuit near Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, perched on a stretch of Carver Street called Whispering Pines. The pines began whispering, as Frank Beacham wrote in Charlie’s Place, Shaggin’ the Night Away, the night Billie Holliday sang there.

During World War II, the only people who heard rhythm and blues were a few bold fellows who made it a habit to jump the Jim Crow rope. “Black music influenced us from the start, and the only good place to hear it was on the Hill,” said South Carolinian shag legend the late Billy Jeffers. Another such fellow was a North Carolinian, Malcolm Ray “Chicken” Hicks. Hicks grew up around blacks, and it wasn’t a big deal to watch blacks jitterbugging at a Durham armory.

Hicks served in the U.S. Coast Guard and washed up in a club-happy place, Carolina Beach, in 1943. Back then, he said, “It was like a state fair, 24 hours a day. There were places that had no doors, ’cause they were always open.”

Hicks was such a fervent appreciator of this music that he became a pioneer. Jim Hanna, a former merchant marine, first placed African-American jump blues on his piccolo, or jukebox, at his Tijuana Inn in Carolina Beach at the behest of Hicks. Hanna called the amusement company in Wilmington that stocked his jukebox and had them bring over some music they regularly took to the black joints down the road. Soon the box that sat just to the right of the entrance to the long and narrow club was blaring tunes unheard of in postwar white America.

Hicks had an affinity for black music and white liquor. On his moonshine-purchasing trips to the African-American community of Seabreeze, Hicks heard popular songs by black artists such as Joe Liggins & The Honeydrippers, Louis Jordan & His Tympani Five, Lionel Hampton, and Wynonie Harris, forebears of the budding jump-blues style music emerging out of the swing and big band traditions.

Hicks liked to show off the new steps he picked up from Seabreeze. When he hit the dance floor, people gathered around for the show. “I’m gonna tell you the truth, I didn’t call it anything,” he said in 1996. “I couldn’t stand it, how they all called it the jitterbug. All I said was, ‘Come on, let’s go jump awhile.’”

Hicks was more than an exceptional dancer. He changed the music whites listened to. He helped bring blacks’ “bop” sound to whites, and that, in part, would give rise to the “beach music” sound, and the shag to go with it. “I got chummy with the jukebox changers. I’d say, ‘Bring that record and that record.’ I got rid of Glenn Miller in Carolina Beach jukeboxes.”

The music proved infectious, and people adored its source. As the nation was coming out of the Great Depression, the jukebox secured a reverent place in Americana and shagdom. Harry Driver, considered the “Father of the Shag” by some, lived in Dunn, North Carolina. He recalled listening to “race” and Hit Parade music in 1945 at White Lake’s Crystal Club. There they danced to “suggestive” music banned in the segregated Carolinas. They paid scant attention to the bans. Said Driver, “We had integration 25 years before Martin Luther King Jr. came on the scene. We were totally integrated because the blacks and whites had nothing in our minds that made us think we were different. We loved music, we loved dancing, and that was the common bond between us.”

As the big-band era died, rhythm and blues came on strong, and racial barriers softened. The color line began to wash out, bleached by black musicians’ crossover to white audiences, thanks to guys like Hicks who got their records into white jukeboxes. Vinyl from artists such as Bull Moose Jackson and LaVern Baker could now be heard. More and more whites turned to black music at the beach pavilions, although to do so was perilous. Sometimes the KKK showed up, showering bullets, slurs, and mayhem.

Said one veteran shagger, “You could only hear that stuff when you were at the beach and away from your parents. The whites loved what they heard, and no sheriff was going to hold them back.”

That was many, many years ago.

***

There’s an old dictum. “The more things change the more they remain the same.” Mostly whites dance the shag today. Young blacks consider it a dance performed to “white music.” Black musicians, including Maurice Williams of Maurice Williams & the Zodiacs, say their own kids refuse to listen to it. “The beginning of beach music was predominantly rhythm and blues,” Williams said. “But today if you say to a young black man, ‘come on, let’s go and listen to a beach music show,’ he’ll say, ‘I ain’t going to that white music.’ The average black kid in his 20s or 30s doesn’t know what this is all about.”

Beach music has its roots in rhythm and blues, but so much has transpired since those early days that the music’s history is lost on the very descendants of those who created it.

Send A Letter To the Editors