The opening notes to Beethoven’s Fifth might be one of the most easily recognizable musical passages ever written. But to unaccustomed ears, the symphony’s opening can be confounding, explains Boston Globe critic Matthew Guerrieri. Guerrieri visits Zócalo to discuss what makes this symphony and its composer special. Below is an excerpt from his book, The First Four Notes: Beethoven’s Fifth and the Human Imagination.

The first thing to do on arriving at a symphony concert is to express the wish that the orchestra will play Beethoven’s Fifth. If your companion then says “Fifth what?” you are safe with him for the rest of the evening; no metal can touch you. If, however, he says “So do I”—this is a danger signal and he may require careful handling.

—Donald Ogden Stewart, Perfect Behavior (1922)

Jean-François Le Sueur was not quite sure what to make of Beethoven’s Fifth. Le Sueur was a dramatic composer, a specialist in oratorios and operas, and the Parisian taste for such fare (along with Le Sueur’s career) had persisted from the reign of Louis XVI through the Revolution, through Napoléon, through the Restoration. For audiences suddenly to be whipped into a frenzy by instrumental music—as they were in 1828, when a new series of orchestral concerts brought Paris its first sustained dose of Beethoven’s symphonies—was something curious. Le Sueur, nearing 70, was too refined to fulminate, but he kept a respectful distance from the novelties—that is, until one of his students, an up-and-coming enfant terrible named Hector Berlioz, dragged his teacher to a performance of the Fifth. Berlioz later recalled Le Sueur’s postconcert reaction: “Ouf! I’m going outside, I need some air. It’s unbelievable, wonderful! It so moved and disturbed me and turned me upside down that when I came out of my box and went to put on my hat, for a moment I didn’t know where my head was.”

Jean-François Le Sueur was not quite sure what to make of Beethoven’s Fifth. Le Sueur was a dramatic composer, a specialist in oratorios and operas, and the Parisian taste for such fare (along with Le Sueur’s career) had persisted from the reign of Louis XVI through the Revolution, through Napoléon, through the Restoration. For audiences suddenly to be whipped into a frenzy by instrumental music—as they were in 1828, when a new series of orchestral concerts brought Paris its first sustained dose of Beethoven’s symphonies—was something curious. Le Sueur, nearing 70, was too refined to fulminate, but he kept a respectful distance from the novelties—that is, until one of his students, an up-and-coming enfant terrible named Hector Berlioz, dragged his teacher to a performance of the Fifth. Berlioz later recalled Le Sueur’s postconcert reaction: “Ouf! I’m going outside, I need some air. It’s unbelievable, wonderful! It so moved and disturbed me and turned me upside down that when I came out of my box and went to put on my hat, for a moment I didn’t know where my head was.”

Alas, in retrospect, it was too much of a shock: at his lesson the next day, Le Sueur cautioned Berlioz that “All the same, that sort of music should not be written.”

In 1920, Stefan Wolpe, then an 18-year-old student at the Berlin Hochschule für Musik, organized a Dadaist provocation. He put eight phonographs on a stage, each bearing a recording of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. He then played all eight, simultaneously, with each record turning at a different speed.

A socialist and a Jew, Wolpe would flee Nazi Germany; he eventually ended up in America, cobbling together a career as an avant-garde composer and as a teacher whose importance and influence belied his lack of fame. (The jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker, shortly before he died, approached Wolpe about lessons and a possible commissioned piece.) In a 1962 lecture, Wolpe recalled his Dada years, revisiting his Beethoven collage; in a bow to technological change, this performance used only two phonographs, set at the once-familiar 33 and 78 r.p.m. Wolpe then spoke of “one of the early Dada obsessions, or interests, namely, the concept of unforeseeability”:

That means that every moment events are so freshly invented,

so newly born,

that it has almost no history in the piece itself

but its own actual presence.

*

If today we regard Le Sueur’s frazzled confusion as quaint, it is at least in part because of the subsequent ubiquity of the Fifth Symphony. The music’s immediacy has been forever dented by its celebrity. Wolpe’s eightfold distortion can be heard as a particularly outrageous attempt to re-create Le Sueur’s experience of the Fifth, to conjure up a time when the work’s course was still unforeseeable. It is an uphill battle—in the two centuries since its 1808 premiere, Beethoven’s Fifth has become so familiar that it is next to impossible to re-create the disorientation that it could cause when it was newly born.

The disorientation is built right into the symphony’s opening. Or even, maybe, before the opening: the symphony begins, literally, with silence, an eighth rest slipped in before the first note. A rest on the downbeat, a bit of quiet, seems an inauspicious start. Of course, every symphony is surrounded by at least theoretical silence. Though, in reality, preconcert ambient noise, or at least its echoes—overlapping conversations, shifting bodies, rustling programs, air-conditioning, and so on—may in fact bleed into the music being performed, we nonetheless create a perceptive line between nonmusic and music, enter into a conspiracy between performers and listeners that the composer’s statement is self-contained, that there is a sonic buffer zone between everyday life and music. (Like most conspiracies, it thrives on partial truths.) The obvious interpretation is that silence functions as a frame for the musical object. The less obvious (and groovier) interpretation is that the music we hear is but one facet of the silence it comes out of.

This is almost certainly not what Beethoven was thinking about when he put a rest in the first measure of the Fifth Symphony. But, were Beethoven really trying to mess around with the boundary between his symphony and everything outside of it, he would have been anticipating the French philosopher Jacques Derrida, the guru of deconstruction, by nearly 200 years. Derrida talks about frames in his book The Truth in Painting, noting that when we look at a painting, the frame seems part of the wall, but when we look at the wall, the frame seems part of the painting. Derrida terms this slipstream between the work and outside the work a parergon: “a form which has as its traditional determination not that it stands out, but that it disappears, buries itself, effaces itself, melts away at the moment it deploys its greatest energy.”

Our minds dissolve the frame as we cross the Rubicon into Art. But Beethoven drags the edge of the frame into the painting itself, stylizing it to the point that, for anyone reading the score, at least, this parergon refuses to go quietly, as it were. Beethoven waits until we’re ready, then gruffly asks if we’re ready yet.

We can see the silence on the page, in the form of the rest. But do we hear it in performance? The rest completes the meter of 2/4—two beats per measure, with the quarter note getting the beat—which, normally, would mean that the second of the three following eighth notes would get a little extra emphasis. But most readings give heavy emphasis to all three eighth notes, steamrolling the meter (which is really only one beat to a bar anyway—more on that in a minute). Paleobotanist, artist, and sometime composer Wesley Wehr recalled one consequence of such steamrolling:

Student composer Hubbard Miller, as the story goes, had once been beachcombing at Agate Beach. He paused on the beach to trace some musical staves in the sand, and then added the opening notes of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. Hub had, however, made a slight mistake. Instead of using eighth notes for the famous “da, da, da, dum!,” Hub had written a triplet. He had the right notes, but the wrong rhythm—an easy enough mistake for a young lad to make. Hub looked up to find an elderly man standing beside him, studying the musical misnotation. The mysterious man erased the mistake with one foot, bent down, and wrote the correct rhythmic notation in the sand. With that, he smiled at Hub and continued walking down the beach. Only later did Hub learn that he had just had a “music lesson” from Ernest Bloch.

Knowledge of the rest is like a secret handshake, admission into the guild. (Bloch, best known for his 1916 cello-and- orchestra “Rhapsodie hébraïque” Schelomo, was also a dedicated photographer who liked to name his images of trees after composers: “Bloch sees ‘Beethoven’ invariably as a single massive tree appearing to twist and struggle out of the soil.”)

Indeed, one practical reason for the rest is to reassure the performers of the composer’s professionalism. Beethoven knew that any conductor would signal the downbeat anyway, so he put in the rest as a placeholder for the conductor’s gesture. And it’s liable to be a fairly dramatic gesture at that. The meter indicates two beats to the bar, but no conductor actually indicates both beats, as it would tend to bog down music that needs speed and forward momentum. Instead, the movement is conducted “in one,” indicating only the downbeat of every bar.

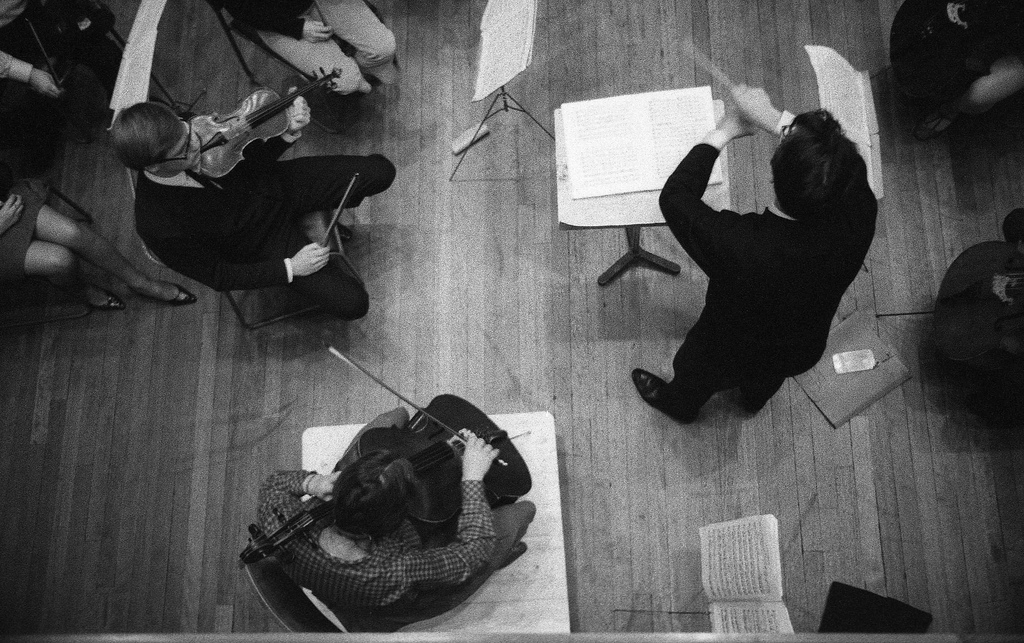

So the conductor has one snap of the baton to get the orchestra up to full speed. And the longer the Fifth Symphony has retained its canonical status, the more that task has come to be seen as perilous. For the two leading pre-World War I pundits of conducting, Richard Wagner and Felix Weingartner, starting the Fifth was no big deal. Wagner takes ignition for granted, being far more concerned with the lengths of the subsequent holds, while Weingartner scoffs at his colleague Hans von Bülow’s caution: “Bülow’s practice of giving one or several bars beforehand is quite unnecessary.” But jump ahead to the modern era, and one finds the British conductor Norman Del Mar warning of “would-be adopters of the baton” suffering “the humiliation of being unable to start the first movement at all.” Gunther Schuller, American composer and conductor, is equally dire, calling the opening “one of the most feared conducting challenges in the entire classical literature.” Del Mar reaches this conclusion: “It is useless to try and formulate the way this is done in terms of conventional stick technique. It is direction by pure force of gesture and depends entirely on the will-power and total conviction of the conductor.”

Send A Letter To the Editors