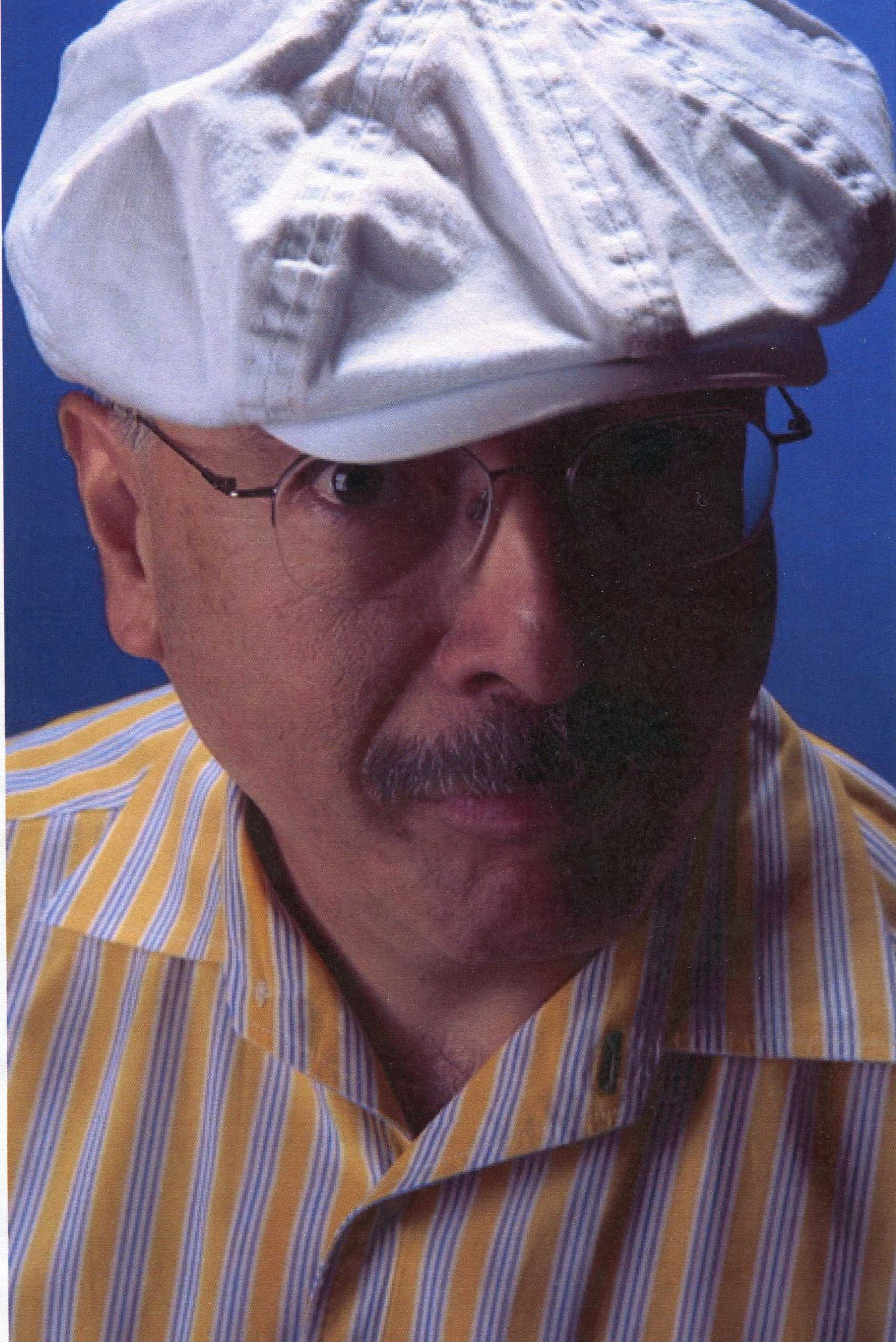

In Squaring Off, Zócalo invites authors into the public square to answer five questions about the essence of their books. For this round, we pose questions to California poet laureate Juan Felipe Herrera, author of Senegal Taxi.

Herrera weaves together a multitude of unexpected voices and genres—poetry, prose, art, dialogue—to give voice to the pain and hope of the children whose lives have been ravaged by years of violence and war in the Sudan.

-

The majority of your work has focused on your experiences as a Mexican-American and the struggles facing your community. Senegal Taxi is set in Sudan; why the change?

Everything is in flux. My notions of self and community change every split second. At a larger level, we live in a fluid social global ocean that we stimulate and that affects us at every instant. Orientations of identity in the ’60s were useful and also detrimental. They kept us apart. In a world of accelerating violence, the poet deals with the paradox of expansion on the piece of paper. I am taking this paradox to task. Africa is key. In other books I have taken on the voices of Puerto Rican and Arab teens as well as gay high schoolers. “They” are not separate from me. That is an illusion. Another paradox. -

Do you want your book’s readers to walk away from the paradoxes you’ve exposed informed, enraged, or wanting to do something?

I will be pleased if readers of my book walk away with meditations on the suffering of the thousands upon thousands of peoples in Sudan, South Sudan, Africa, and the world at large—and perhaps most important, in our own role here, where we stand in furthering these dire and incredible situations—and a new way—at a personal and collective level—of dealing with such a horrific scale of violence. -

You have called this book “a performance poem” and have been called the first successful creator of a new type of “hybrid art.” Why isn’t Senegal Taxi just a book of poems? Or just a novel? Or a performance? What do the different facets of the text bring to it?

Well, I wish all that were true—anyway, the poem is changing. It hangs out on the stage these days and on collaged assemblages. But this isn’t too new—remember Picasso’s collages, Lawrence Stern’s doodles, Frida Kahlo’s poems on lunch paper bags, then there are the first poems of this hemisphere carved into stone at Monte Alban in 300 B.C.? I like all this. Nothing is “just.” It just is. At another level, I like to give the poem room to do its thing, so it can cross-over the wire onto new turf and unwind from its tight, polite journey. Perhaps it will be performed, or painted, or readpaintedperformed? -

What possibilities, if any, are there for poetry online? How would you like your work to “cross-over the wire” into cyberspace?

The possibilities are endless, just like the possibilities inside the poem—I love the possibility of warming up our hearts in as many media as we can come up with and sharing that warmth in endless fashions, don’t you think? -

The voices in the book belong to African children, a village ant, a television broadcast. Which voice was your favorite to create?

My favorite voice to enter was that of Abdullah, the Village Boy with One Eye, the one that lost his way in a sense, somewhere in between Ibrahim ahead of him and Sahel, the little girl behind him. He has more range and depth. However, I do love what happened with the Kalashnikov AK-47—I was most pleased with that voice and find a deep reservoir of energy in that entity and a most surprising inner longing for things that most of us would repudiate.Yet, the thing is, all the voices are really one song. And there are many more.