Debbie Allen’s career has spanned film, television, and theater; acting, choreographing, directing, and producing; and serving as an ambassador and teacher of the arts in Los Angeles and around the world.

She was similarly capacious in talking with UC Irvine English professor and former L.A. Times national correspondent Erika Hayasaki, at an event sponsored by the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs. The conversation was “bouncing,” said Allen, “all over like a microwave,” in front of a large, often laughing crowd at the Petersen Automotive Museum.

Hayasaki opened by inviting Allen to discuss an upcoming piece she wrote, choreographed, and directed at the Brisbane Festival in Australia—a fusion of dance, film, and theater called Freeze Frame.

The story is set in the Leimert Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, explained Allen, and is her reaction to the senseless gun violence she’s read and heard about since she moved here to act in Fame. Freeze Frame opens with a young man robbing and killing a storekeeper, then moves to the police investigation, which ends up taking the life of a different young man, and then explores the stories of young people in the neighborhood. It’s a piece that entertains, it’s got great music, it’s even funny, said Allen. But it also—as theater is supposed to—makes you “think and feel and maybe calibrate your life” in order to find out where you fit into the world.

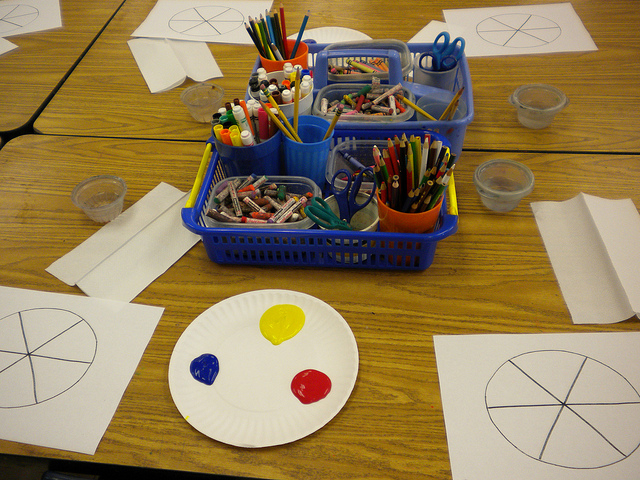

Hayasaki asked Allen to explain the origins and inspiration for the Debbie Allen Dance Academy, which Allen founded in 2001 to teach dance to young people in L.A., and which today brings together dancers from all over.

Allen explained that, while growing up in Texas, she wasn’t allowed to attend ballet school because she was black, so she moved with her mother to Mexico City, where she could train—and where there wasn’t the same pervasive racism as in Texas. Allen recalled eating hamburgers at a Mexico City Woolworth’s for the first time with her sister (the actress Phylicia Rashad): “We thought we were at the Ritz in London. … It was the most amazing thing in life.”

“The word is access,” said Allen. “There’s always going to be an uneven divide in terms of economics. But access.” After her own daughter had to leave Los Angeles to train as a dancer, Allen made it her mission to create a dance school that would serve the region and provide access to aspiring dancers of all backgrounds. Today, 70 percent of students at the academy are on scholarship.

But most students in Los Angeles and across the country don’t have access to arts education. Forty percent of high schools, according to the National Education Association, don’t require arts for graduation. What, Hayasaki asked Allen, are your thoughts on this epidemic?

Allen recounted how, as a cultural ambassador for dance under George W. Bush, she asked him and the first lady to add the arts to No Child Left Behind. We need balance in education, she said—for a lot of reasons, including the fact that students who attend schools where the arts are offered graduate at a much higher rate. “If we could make everybody take a dance class, I could bring world peace, honey,” she said.

A sense of social justice runs through a lot of Allen’s work. Hayasaki asked her to talk about producing the Steven Spielberg-directed Amistad, a film that took her 19 years to get made. Allen told the story of how she discovered the largely unknown story of a slave revolt (that ended up spurring a U.S. Supreme Court case) in a book of essays. She felt like it was her responsibility to share the story with as many people as possible—and that the way to do it was on screen—so she took it to people all over Hollywood. She could get a meeting with anyone—“everyone loved little dancing Debbie”—but they couldn’t connect her and the project: “‘Is there any dancing in it?’” they’d ask. Eventually, Allen got the film made with Spielberg, and shown all over the world, including around Africa. It was a lesson in persistence and commitment.

Allen also has had to break barriers as a female director. She said that lacking fear, possessing creativity, and doing her homework have been the greatest assets in earning the respect of her colleagues. She recalled how an experienced director of photography told her he wasn’t going to be able to light a scene where she had “the whitest boy dancing with the blackest girl.” But she told him he didn’t have a choice—and he figured it out. Sometimes, she said, not knowing everything can be a good thing. And people want direction—even James Earl Jones, whom she directed onstage in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof; every day, he asked her for notes, and every day she had notes for him.

In the question-and-answer session, audience members asked about the arts in L.A. schools, her family roots, and the nature of fame today.

What people or organizations in Los Angeles can supporters of the arts in schools shake up or get behind?

We need to form a committee and go to school board meetings downtown, Allen told the audience. And the effort has to be grassroots. “We have to call out the people we elected,” she said. “We should have a protest and block off the 10 Freeway”—but it should be a positive protest, with dancing and cheering for the arts. This is Hollywood, said Allen; we have no business cutting the arts out of our schools.

Another audience member asked Allen to share her mother’s secrets to raising such talented children.

Allen said that her mother, who turns 90 in July, was an artist herself—a pianist and a poet. She told her children that they had power and they were the best, but she was also unrelentingly tough on them. “She continues to make us know we haven’t gotten there yet,” said Allen.

Is the changing nature of fame today—where social media like YouTube can make anyone a star—lowering the expectations of the young people Allen works with?

“The standard of fame got lowered,” said Allen. “You become famous on a reality show if you eat a frog. Is that talent? If you lose weight, you become famous.” At the same time, social media is “the language of today, of right now.” The kids I’m trying to raise, she said, understand that there has to be more beyond just yourself.

Send A Letter To the Editors