Why do they hate America? What can we do to make them like us? There has been much talk about the promise and limits of U.S. public diplomacy in the Islamic world ever since the 9/11 terrorist attacks and an assumption that our efforts need to be adapted from the Cold War. But many of these discussions ignore that the robust, global system of public diplomacy funded by the State Department from the 1920s until the 1990s pre-dates the Cold War. The U.S. formulated its system of public diplomacy in response to an earlier radical upheaval of the 20th century, the Mexican Revolution, which raged from 1910 to 1920.

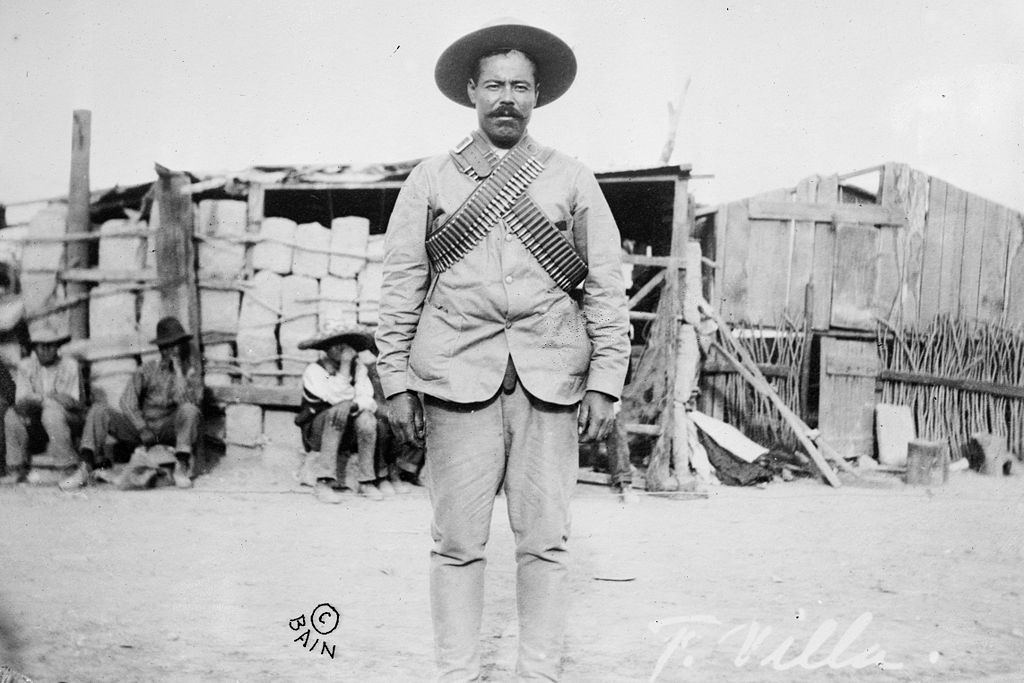

Not unlike the Arab Spring, the Mexican Revolution had multiple chaotic phases, as numerous factions vied for individual rights, land redistribution, and increased popular participation through voting reform. During the most chaotic and politically radical phase of the war, President Woodrow Wilson sent troops to Mexico twice. (He famously said, “I am going to teach the South American republics to elect good men.”) During the first intervention, in 1914, the American military temporarily occupied the Gulf port of Veracruz. During the second, in 1916, General John Pershing led the Punitive Expedition, which unsuccessfully chased Pancho Villa, the charismatic Chihuahua revolutionary. Rather than serving as an education for the Mexican people, as Wilson hoped, these invasions sparked widespread anti-Americanism.

Years of poisoned negotiations between the two nations over losses of property and life followed the end of the revolution—and it didn’t help matters that in the previous century the U.S. had helped itself to half of Mexico. These failures came to a head in 1927, during the presidency of Calvin Coolidge, when James R. Sheffield, America’s ambassador to Mexico, was forced to return to the United States after making statements in public and private to the effect that the Mexican government was “shot through with Bolshevism.” With relations breaking down, fears rose that another invasion of Mexico—to teach them to “elect good men”—was imminent. At the time, the U.S. military already had large occupation forces operating in both Nicaragua and Haiti. U.S. troops had also recently withdrawn from the Dominican Republic. The U.S. threat was real and constant.

But Coolidge turned to public diplomacy instead. His man for the job was Dwight W. Morrow, lawyer for J.P. Morgan and Coolidge’s friend from their days at Amherst College. Though Morrow had no previous diplomatic experience, Coolidge appointed him ambassador to Mexico in October 1927, and the personal connection between the men signaled Coolidge’s deep interest in renewing peaceful cooperation with Mexico. Morrow came without any specific guidance, so instead he deployed his considerable wealth and connections. One of his first acts was to convince the cowboy comedian Will Rogers and the aviator Charles A. Lindbergh to conduct a goodwill tour in Mexico from December 1927 to early January 1928.

Lindbergh was the greatest celebrity in the world at the time, and, in Mexico, the excitement over his arrival could be felt throughout the capital. When Lindbergh got lost in Central Mexico and landed his plane several hours late, Rogers marveled that no one in the crowd, not even President Plutarco Elías Calles, dared leave the airfield, even to have water. Newspapers in both the U.S. and Mexico compared Lindbergh to the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl, a feathered serpent.

Advertisements for products dubiously connected to Lindbergh—shoes, typewriters, and cigarettes—appeared in Mexican papers. The tour was so successful that Lindbergh extended his stay in Latin America, visiting several nations in Central America before landing triumphantly in Havana, Cuba for the 1928 Pan-American Conference.

The celebrity tour had several immediate positive effects. In Mexico, reports heralded the miraculous powers of the new ambassador for bringing Lindbergh to Latin America. In the U.S., a series of fawning articles written under Lindbergh’s byline praised the accomplishments of the Mexican revolutionary state. More immediately, the visit allowed Morrow to spend an extended period of time in close contact with President Calles and other officials. This translated into renewed negotiations over a host of issues. While Lindbergh and Rogers’s goodwill tour did not lead to a quick resolution of all differences, it set an example of cooperation between the nations.

While this was the U.S.’s first major foray into large-scale, peacetime cultural diplomacy, the concept was not new. The United Kingdom had used the British Council to spread its cultural products throughout the world, and France had founded the Alliance Française in 1883 to spread the lingua franca of those who wanted to be comme il faut. Even Mexico engaged in cultural diplomacy, advertising the accomplishments of the revolution through university summer courses meant to appeal to U.S. college students. Still, as a rising superpower in the first half of the 20th century, the U.S.’s discovery of soft power had a tremendous impact on its relations not only with Mexico but also with the rest of Latin America.

Despite Morrow’s success, Coolidge and Herbert Hoover were reluctant to set aside any permanent funds for cultural diplomacy. Those came after Franklin D. Roosevelt announced the Good Neighbor Policy in 1933. Roosevelt denounced military intervention and pledged that the U.S. would no longer interfere in the internal affairs of its neighbors. But it was never intended to be a policy of isolationism, as is often mistakenly claimed. While military intervention was prohibited, cultural intervention was acceptable. As a result, the Roosevelt administration encouraged student exchanges between the U.S. and Latin America and promoted U.S. film, radio, and books on a large scale during World War II.

Public diplomacy had a strong impact in Mexico. Anti-Americanism did not disappear, but serious disagreements between the two nations no longer caused public ruptures. Even when President Lázaro Cárdenas nationalized the Mexican oil industry in 1938, at the expense of American investors, the resulting controversy was brief. Over time, bilateral exchanges also encouraged Mexican elites to study north of the Rio Grande, forming transnational networks that persisted for decades. Mexican citizens may not have been taught directly how to “elect good men,” but they were exposed to U.S. ideas in a way that would have been impossible had military intervention continued to define American foreign policy.

The programs launched to sway post-revolutionary Mexico wound up serving as the testing ground for many better-known Cold War cultural programs, such as the Fulbright Program, the Peace Corps, and Voice of America. Although America’s cultural diplomacy infrastructure was largely defunded in the 1990s, when the United States Information Agency was absorbed by the Department of State, the remaining programs continue to have an impact on world affairs and offer models of how to proceed in places like Egypt. Indeed, in 2011, the Embassy of the United States in Cairo co-sponsored an American Idol-style contest called “Sing Egyptian Women, Let the World Hear You.” Such efforts hint at the sort of outreach the United States might again put at the forefront of its engagement with the Middle East.

At its core, public diplomacy takes the question “Why do they hate us?” and answers, “Because they don’t know us well enough.” In the case of Mexico, U.S. public diplomacy played a crucial peacemaking role that improved relations and endures on both sides of the border. Today, with international tensions as high as ever, it is time we relearned how to harness American culture to serve its politics.

Send A Letter To the Editors