In 2012, Barack Obama was re-elected with the votes of less than a third of the population of Americans who are eligible to vote. That’s right—because many who are eligible to vote don’t register and many who register don’t vote, Obama is a minority president. But in this regard, he is hardly the first. Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush won the votes of only a quarter of those eligible.

As someone who grew up in Australia, I am surprised by such results. My home country does not allow low voter registration or low turnout to dent its leader’s claim to be truly representative. Instead, Australia requires eligible voters to vote.

Today, 23 countries have compulsory voting laws. In these countries, voter participation is as much as 30 percent higher than it is in United States. Since nationwide compulsory voting was introduced in Australian elections in 1924, the turnout has never fallen below 90 percent.

Australia is no political paradise. Politicians there are often just as daft as the ones in America. Campaigns produce plenty of nonsense. Australians, like Americans, are not always the informed voters and engaged citizens they should be. And some Australians participate in an apathetic practice called “donkey voting”—simply numbering the candidates one through ten instead of ranking them according to preference, spoiling ballots by defacing them, or placing no vote on a ballot.

But the percentage of informal votes remains small—around 4 percent in most counts. And they hardly mitigate the distinct advantages of compulsory voting. There’s no other form of voting in a democratic election that gives as accurate an indication of what an entire country is thinking politically.

In ethnically diverse countries formed by immigration, such as Australia (and the United States), it is hard to overstate the value of compulsory voting. The system allows the greatest proportion of voices to be heard in an election, and in doing so promotes social cohesion and the value of political participation. Watching my parents vote in every election, I understood the importance of the duty—and of Australian citizenship. Compulsory voting creates culture and expectations. I can’t name one person I know who has been levied the standard $20 fine for not voting.

For all these reasons, compulsory voting is one Australian affinity that, unlike Vegemite and Mel Gibson, Americans would do well to emulate.

Compulsory voting—on display this weekend in the country’s national elections—also addresses many of the concerns that Americans are raising about the state of their own democracy. Chief among these is the relatively weak representation of the views and circumstances of lower-middle-class and poor Americans in the nation’s politics.

Political science research establishes that when voting is voluntary, as it is in the U.S., those with higher socio-economic status—people with time and money—are more likely to cast a ballot. According to the U.S Census Bureau, in the 2008 election, 76 percent of voters earning a median income of $50,000 or more voted, while only 59 percent of Americans earning less than that cast their ballots.

With compulsory voting, the elections—and the debate around them—would be broader. Since so few Americans actually vote, American politicians don’t have to appeal to the whole country. Instead, they cater naturally to the groups most likely to vote for them, and, in office, they create narrowly focused policies and laws with the aim of turning out those same voters in the next election cycle. Compulsory voting also would diminish the value of negative advertising, which is mostly designed to reduce turnout for political opponents.

Yes, there are objections to compulsory voting, but, under scrutiny, criticisms of the system seem minor compared to the advantages. The most common complaint raised in the U.S. against compulsory voting is that it infringes on one’s freedom not to vote. But if requiring voting every two or four years is a suppression of rights, it’s a fairly modest one—and far less time-consuming than the government coercions of paying taxes, jury duty, or receiving a basic education.

And it’s far from clear that compulsory voting is coercive at all. In 1971, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that compulsory voting did not amount to a violation of the right to “freedom of thought, conscience and religion.” Compulsory voting only requires voters to go to the polls. It does not dictate that the ballot be marked in any particular way or at all. And, if democracy is a public good from which citizens benefit, there should be a reciprocal duty for citizens to participate in its function.

Opponents of compulsory voting often fret that it could skew election results or undermine their quality. Some worry that compulsory voting benefits the liberal party, on the assumption that minorities and younger people are the missing voters in most elections. Others suggest that the additional voters are less informed and will make choices of dubious quality compared to voluntary voters. “The median voter is incompetent at politics,” Jason Brennan, a professor of ethics, economics, and public policy at Georgetown University, argued in The New York Times. “The citizens who abstain are, on average, even more incompetent. If we force everyone to vote, the electorate will become even more irrational and misinformed. The result: not only will the worse candidate on the ballot get a better shot at winning, but the candidates who make it on the ballot in the first place will be worse.”

But there is little evidence to back either objection. Despite its compulsory voting laws, Australia’s political landscape has resembled that of the United States—domination by two major parties on a familiar liberal to conservative spectrum. A 2008 study by political scientist John Sides of George Washington University showed that compulsory voting would have had little impact on the results of American presidential elections between 1992 and 2004. (Sides suggests compulsory voting might only be a factor in some tight races.) In either case, if the goal of democracy is to have as many citizens participate and be represented as possible, compulsory voting’s advantages are undeniable.

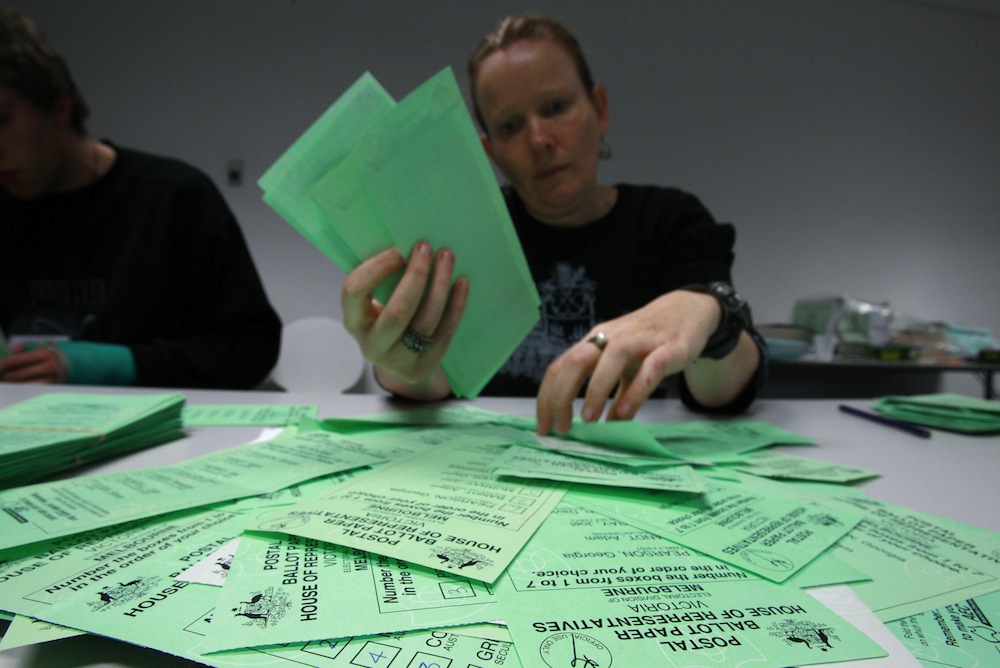

Its adoption in the United States also would help Americans get past their toxic debate over laws that would make it harder to vote. When voting is compulsory, there are strong incentives for voter-friendly election laws. Australia is a voter’s paradise. Election Day is always on a weekend. Postal and early voting are readily available. The Australian Electoral Commission encourages simple registration practices and ensures that there are mobile polling stations as well as booths in hospitals and nursing homes. Given all these advantages, it’s no surprise that compulsory voting is popular, with public approval at about 75 percent.

As Americans battle over voter suppression and disenfranchisement in places like Texas, North Carolina, and Florida, compulsory voting looks like a way out. If every eligible adult were required to vote, states would have little choice but to overhaul their electoral systems and make voting as accessible as possible. This would focus attention back on the issues, not the process—and would make American democracy more representative, and Election Day an occasion for everyone.

Send A Letter To the Editors