I first learned black history from Ms. Gilliard, my teacher at 96th Street Elementary School in Watts, who selected me to present the “I Have a Dream” speech in a school-wide assembly. In hindsight, I see this as the beginning of my understanding of the struggle of African-Americans in our fight for social justice and economic equality. Growing up, I remember different times when my mother, sister, and I were evicted and had to sleep in the back of our car, in a hotel, or in a homeless shelter. My father was addicted to drugs, and I don’t remember meeting him until I was 6 years old and living in a halfway house. This story is too familiar to young black males. But unlike the young men who ended up in gangs or went to prison, I was fortunate enough to have amazing people in my life who helped me persevere. I graduated from Morningside High School in Inglewood and enrolled at UCLA. Through all of this, I thought I understood poverty, racism, segregation, and inequality.

But not entirely. Not until I went to South Africa.

The trip was in 2001, my third year at UCLA. I chose to go to South Africa on a study abroad program because I wanted to visit Africa—what I was always told was the “Motherland.” When I toured the townships of Cape Town, I was shocked and humbled by the sight of shanty towns: small, impoverished cities made up of crudely built dwellings. When we stopped in Langa to get water, the abject poverty was hard to reconcile with the version of poverty I experienced, and the images of American prosperity upon which we all were raised. I came face to face with my own privilege.

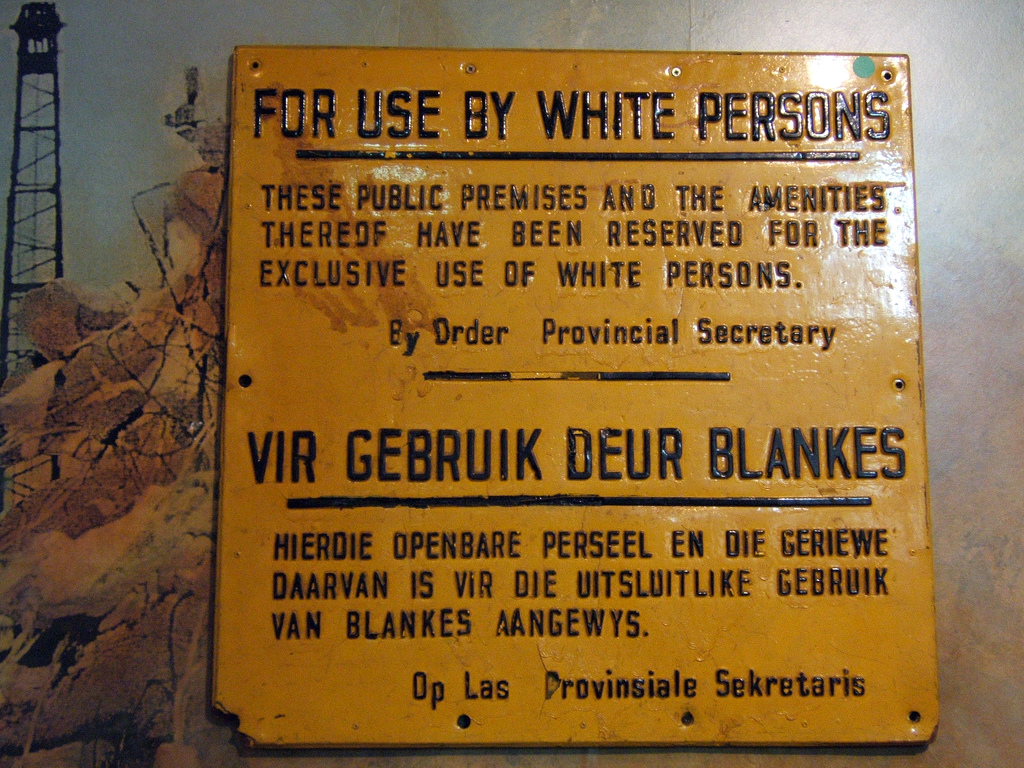

As we traveled to Cape Town District Six, where 60,000 residents were compulsorily removed during the apartheid regime, I saw the deplorable effects of racism and forced segregation. As I walked the stony roads, I could not help but think of my experiences moving from home to home and wondered how those South African children felt. The District Six Museum stood as a monument that taught us about the legal structure and systematic denial of life and liberty to the South African majority during apartheid. And then it was on to Robben Island, where the profound moment of standing in Nelson Mandela’s cell forced me to think about the legacy I wanted to leave the world.

Why did South Africa change me? Somehow, being there, and traveling through the country, connected my past to my future. Given all the damage apartheid caused to native South Africans, I still saw so much hope. Somehow, the challenges I experienced growing up didn’t feel so heavy anymore. As we traveled around the country, I learned more about the leadership of the African National Congress, read the works of Desmond Tutu, and visited the Transvaal where Zulu men, at the Battle of Isandlwana in 1879, threw off the shackles of British rule. These experiences created a desire to evaluate the social, economic, and political conditions caused by racism. The travel made me more human. When I saw South African children, I saw myself.

By the end of my trip to South Africa that August, I decided that I would live a different life, one that would focus on loving and caring for people, because of all that was around them.

My journey from there would not be a straight line—shortly after I returned from South Africa, the U.S. was attacked on September 11, and I enlisted in the U.S. Navy. Through my travels in the Navy and nearly five years I spent in the service—including a tour in Iraq—I came to see the story of South Africa in other nations. This gave me an even greater desire to become an agent of change. I returned to UCLA to fulfill the commitment I’d made to myself first in South Africa.

Concerned about the issues facing black males like me, I was selected to become a McNair research scholar, where I established my foundation as a researcher and scholar committed to addressing these issues. This trajectory took me back full circle, to Morningside High, where I conducted my research with black male youth. The need of these young men led me to develop an academic intervention program in 2006 called the Black Male Youth Academy (BMYA) where I worked with 25 African-American male youth in grades nine to 12 to mitigate gang violence, imprisonment, and recidivism. I taught students how to conduct research and also about their heritage, so they could become self-reliant, more aware of (and critical of) conditions in the communities around them, and more powerful as advocates. In our first cohort, out of the eight young men who graduated, five were accepted to a four-year university, two attended a community college, and one went to a trade school. These were young men from a high school where the graduation rate was 36 percent for black males at the time. (None of them went to UCLA or other elite institutions, which inspired me to become an advocate for higher education access, diversity, and affordability—and a University of California student regent.)

The success of the BMYA spurred me to go to graduate school, pursue a Ph.D. in education, and launch an educational nonprofit called the Social Justice Learning Institute (SJLI) with the goal of spreading our success nationally. We’re now serving more than 250 boys and men of color throughout Los Angeles County, with plans to work in Sacramento this year. Although we were helping young men achieve academic success, they were still living in an environment where they could die because of unhealthy or unsafe food they ate. As a result, SJLI has developed a local food system with community gardens, a community-supported agriculture program, and five Healthy Lifestyle Centers in the communities of Inglewood and Lennox.

Every time I see lives changed because of what we’re doing at SJLI, I think of my experiences in South Africa. I am reminded that even when the world seems upside down I have the power to make it better. If change is possible in my community, it is possible in every community where people face racism, segregation, and inequality. We must remember our journey to stand in our power. This is the purpose and legacy of Black History Month.

Send A Letter To the Editors