Venue

Mercado1416 Fourth Street

Santa Monica, CA

The Tab

(1) blood orange margarita————————–

$13.00 + tip

Most of what I know about the restaurant business I learned from Anthony Bourdain. Bourdain’s 2000 tell-all memoir of his life as a high-end restaurant chef, Kitchen Confidential, was rife with sex, drugs, and drinking. The restaurant business, according to Bourdain, was brutal—and you had to be something of an outlaw to survive.

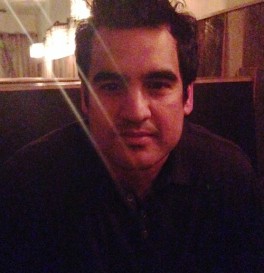

He rides a motorcycle, but Jesse Gomez, dressed in a dark, collared shirt and fiddling with his smartphone at Mercado, his Santa Monica eatery, doesn’t strike me as an outlaw. And, I soon find out, contrary to what Bourdain would have me believe, the restaurant business is no longer the Wild West, either.

Bourdain described degenerate kitchen staff and managers serving up nearly spoiled seafood to clueless customers. But at the four restaurants Gomez owns in Los Angeles—his family’s Highland Park restaurant, El Arco Iris; downtown’s Yxta; and two locations of Mercado in Santa Monica and Fairfax—his customers are incredibly savvy. “We can’t put mediocre stuff out there,” Gomez explains. When it comes to food, drinks, and service, today’s diners know what they want and what they’re willing to pay for it.

Although he was born into the business and grew up working alongside his family at El Arco Iris, which his grandparents started in the 1960s, Gomez is a restaurant owner for and of our current, food-obsessed age. He’s a serious businessman who loves the creative side of running restaurants—purchasing the art on the walls, collaborating with architects and designers, and occasionally offering input on a dish. And although he operates restaurants all over town, including a new “Mexican seafood joint” opening in Eagle Rock this summer, he’s still obsessively focused on the details. He loves having his hands in the food, the drinks, the managing of people, and crunching the numbers to figure out how much you can charge for a cocktail if you buy a bottle of tequila for $20. With that smartphone in his hands, he shows me how he can adjust Mercado’s lights and music up and down as we sit in a booth in the restaurant’s still empty mezzanine at 5 p.m. on a Monday evening.

This is technically Gomez’s day off, although he interviewed a potential manager for the new restaurant over lunch, and he treats our drinks like he’s working, drinking water as I sip a blood orange margarita. After living in Los Feliz and Silver Lake for over a decade, he recently moved to Venice. “I got the idea in my head after we opened in Santa Monica and I was here seven days a week,” he says. “I envision, on a Saturday night, working here, and starting my weekend going home, hanging out, and enjoying being close to the water.”

Proximity to the beach feels like vacation to Gomez, who grew up on the Eastside, in Eagle Rock and Highland Park, and went to middle and high school in South Pasadena. He, his grandparents—who emigrated from Querétaro, Mexico—his mother, brothers, and sisters all worked at El Arco Iris. His mother wanted him to focus on school, get an advanced degree: “I don’t think she wanted me to be slaving away in a restaurant 12, 14 hours a day,” he says. “But that’s what happened.”

He left L.A. and headed east to Princeton, where he studied psychology—without taking a single economics or business course—and craved his family’s burritos each time he came home. He enrolled at Loyola Law School but left after a semester. “I just kind of knew that it wasn’t for me,” he says. He thought he’d be bored sitting behind a computer doing research, going to court a certain number of days a week: “Feeding attorneys is better than being an attorney,” he says.

So he went back to the restaurant industry. In the mid-1990s, he got a job as a restaurant manager with the Hillstone Restaurant Group (which owns Houston’s and Hillstone, among other brands). He says he tells people 80 percent of what he learned about restaurants he learned in his year-and-a-half at Hillstone, which included spending time training in the kitchen—a requirement for managers that Gomez later borrowed for his own restaurants. The experience at Hillstone also showed him the days of the mom-and-pop shop are over; it’s not enough for the customers to know your name, as they did at El Arco Iris. A restaurant must be a destination. After leaving the corporate restaurant world, Gomez returned to his family’s restaurant and decided to remodel to transform it into such a destination, in part by adding a full bar in 2006. Business soon increased by 30 percent.

Five years ago, in February 2009, Gomez opened his first restaurant on his own, downtown’s Yxta (named for his Loyola criminal law professor, Yxta Maya Murray). Gomez runs the kinds of restaurants he wants to eat in: “I like to go to places that aren’t stuffy,” says Gomez, who wears a suit about twice a year. But his restaurants, and the places he likes to frequent, care about maintaining a certain level of quality. “These aren’t fine-dining restaurants, but I tell my staff to err on the side of fine dining,” he says.

The sleek, hip vibe and attention to service at Gomez’s restaurants are also a conscious effort to overcome the stigma of Mexican food as lower-end cuisine. We’re charging $25 for a steak where someone else would be charging $13 or $14.” So it has to be a great steak served in a great atmosphere by a great staff. “I never want people to come in here and say, ‘Wow I just overpaid for mediocre Mexican food and had mediocre service,’” says Gomez.

Gomez is “definitely not” making the food at his restaurants, although he collaborates closely with his partner, chef José Acevedo. Gomez calls Mercado, whose first branch he opened in Santa Monica in 2012, “a traditional Mexican restaurant with some twists”; he doesn’t like calling it “modern Mexican” because he doesn’t think food like nopales and homemade tortillas are modern, and he doesn’t want to work within strict boundaries. Which is why he’s not calling his next restaurant, Maradentro, a mariscos place—that would preclude putting Acevedo’s carnitas and a burger on the menu.

The challenge for Gomez now is the same one faced by every 21st-century entrepreneur: building the brand. “We’re trying to be smart about where we go and how we do it,” he says. He’s not shy about his aspirations: He wants to grow the business as much as he can, and open as many restaurants as he can, while keeping them all up to the same high standard. “We might get to a place where we have eight restaurants; seven are great, one’s mediocre,” he says. “Let’s not expand until all eight are great.” One of his dreams is to open a restaurant in San Francisco, where there are innovative taquerias and Mexican street food, but fewer sit-down, higher-end Mexican restaurants. But he doesn’t see himself going out of state any time soon. “To me, California Mexican restaurants are special,” he says—thanks to some combination of the availability of ingredients, the presence of so many Mexicans, and sheer proximity to Mexico.

The buzz downstairs at Mercado is growing louder as I finish up my margarita and Gomez and I prepare to part ways. With Bourdain on my mind, I’d envisioned us throwing back shots—or at least sipping some tequila straight-up. I’m comforted by the ink on Gomez’s arm—a “Mercado” tattoo he got about a month ago. I joke that it’s not something you’d see on a lawyer’s arm, but he finds the suggestion less outlandish—he might have done it if “I made partner and wasn’t going anywhere anytime soon.”