One day when I was nearly 9 years old, I beat up a boy so badly that he fell to the ground.

I hadn’t done anything wrong. It was a friendly practice sparring match during an average afternoon karate class. Instead of accepting his defeat gracefully, he got up, furious, and proceeded to chase me around the building. Being the shy, non-confrontational person I was back then, I let him do this until he was scolded and told to calm down. I had been told that “boys never like getting shown up by girls” but never quite understood it until that day.

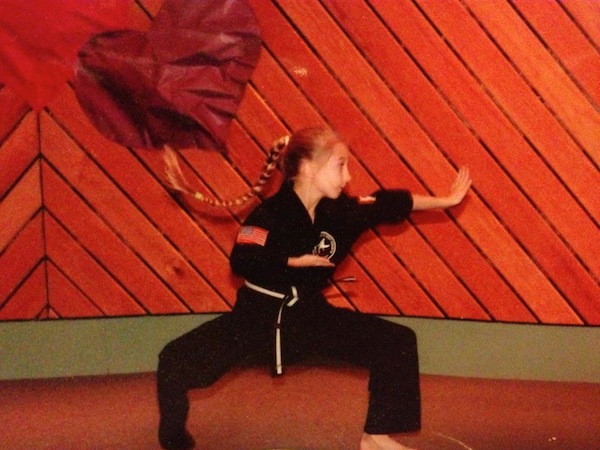

Growing up in karate made me different, in some ways that were obvious from the start and in other ways that become more apparent as I get older. In elementary school, when my friends dreamed of becoming a gymnast or dancer—elegant and graceful—I dreamed of being able to break boards with my feet. I dreamed of being able to use a sai (a kind of sword). I dreamed of being powerful and courageous.

I started at age 7, in a trial class offered by Arizona’s Best Karate at my charter elementary school. I liked it enough that I ended up enrolled within weeks. When my mom asked, “Are you sure you want to sign up?” and I answered “Yes,” I knew that I was in until I achieved whatever goals I set. I am not a quitter.

Almost every afternoon was the same routine: put my uniform on, drive to karate with mom, bow (out of respect) at the door, put my sparring gear in the corner of the room, and bow (again, out of respect) onto the mat for class.

In Arizona, karate was officially a co-ed sport, but I climbed the ladder of belts with mostly boys at the same level and age as me. In fact, I don’t remember there being any other girls in my immediate belt level. This didn’t bother me back then—I didn’t pay attention to gender roles (nor did I understand the term). I just thought I was a tomboy.

I battled boys in practice but could not spar with boys in competition for reasons unknown to me. In some ways, that made competition harder. When too few girls signed up for sparring events, the next thing I knew they had combined my age group with the one above me. This was unfair—most of those girls had already reached puberty. During one competition, I found myself sparring against a woman twice my size. I was scared, but I knew my mom was watching every move. I was kicked down several times (both emotionally and physically) but finished the competition.

Karate taught me to stick to my guns. At a show-and-tell in elementary school, I performed a karate form to “The Star-Spangled Banner.” A karate form is similar to a dance number, but instead of twirls and leaps, it consists of kicks, spins, and punch combos. I specifically remember nailing the performance and being proud of myself as I kicked the air above my head while holding our nation’s flag in one hand and the Japanese flag in another. The class, however, was more impressed with the ballerina and the tap dancer than the “tomboy karate girl.” I didn’t care.

I also learned to use every little advantage. One thing that surprisingly helped me in karate was my long, blond hair. Back then, it reached down to my lower back and when I put it in a braid, it looked and acted like a whip during my forms and karate moves. I occasionally put spikes made of tin foil in my hair and claimed it was my “personal weapon”—something none of the boys could do.

As I climbed in belt status, I began to compete more. I never placed first in a tournament—though I won a few second-place awards—but I always took away new lessons about sportsmanship, dedication, and hard work. As I neared the end of my training at 10 years old, I went to practice every afternoon and on Saturdays. On a typical Saturday before I took the black belt test, my day’s agenda looked something like this:

6 a.m.: Hike Pinnacle Peak (a popular hiking trail in the Salt River Valley, where I lived)

9 a.m.-12 p.m.: Karate practice at the studio (sparring, weapons, and self-defense)

12-12:15 p.m.: Lunch break

12:15-5 p.m.: Work on previously taught forms and our personal, made-up forms

I’m no dancer, but I’m pretty sure our training was just as rigorous.

I graduated with my black belt in November 2005. I was in excellent physical shape and had great confidence, but I couldn’t wait to finish. I had grown tired of the constant practice and lack of social life outside the studio. After I quit karate, my friendships with the boys in my belt class slowly fell apart. I think it had more to do with our age—we were entering our preteen years—than with any damage I might have inflicted upon them while sparring.

Looking back now, I feel bittersweet about ending my career the day I got my black belt. Sometimes I think: “Where would I be now if I had continued?” Hands down, karate had more of an impact on my life and growth than any other experience I had growing up. I’ve used what I learned—respect, courage, focus, determination, commitment, and hard work—on a daily basis in high school and now college as I prepare for a professional career.

I can only hope that my future children will understand this, set goals for themselves at a young age, and pursue a hobby of their own choosing—no matter what anyone else thinks.

Send A Letter To the Editors