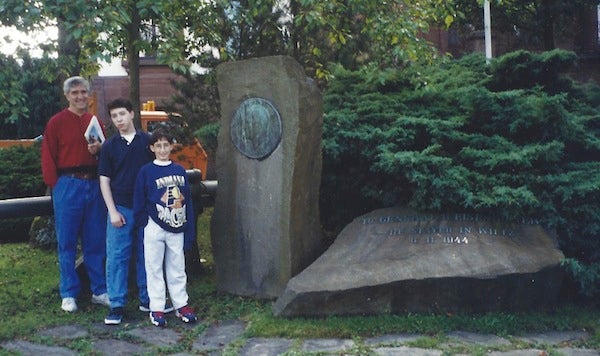

Like many World War II veterans, my father, Harry L. Fox, rarely spoke about his participation in the war. One can only suppose he did not want to awaken the ghosts of death, destruction, and hardships he had witnessed. Whenever I suggested we take a trip to Europe to visit the old battlegrounds, he refused, saying he would never go back there. However, when I informed him in 1997 that my wife, Cydney, and our sons, Zack and Eric, 15 and 12 years old at the time, were going to Europe and would visit historical sites, he told me to visit Wiltz, Luxembourg, where he spent some time during the war.

My dad, a technical sergeant, was in Headquarters Company, 1st Battalion, 328th Regiment, 26th Yankee Division in the U.S. Third Army under the command of Lieutenant General George S. Patton. Remember in the movie Patton, when George C. Scott, as Patton, tells a meeting of incredulous generals that his Third Army could send three divisions against the German offensive (later known as the Battle of the Bulge) in 48 hours? The 26th Division was one of the three. Dad recalled that the Army was in a town that rhymed with “nylon” (which turned out to be Arlon, Belgium) when the order came. They marched into battle. That’s how the Yankee Division ended up in Wiltz.

My dad, a technical sergeant, was in Headquarters Company, 1st Battalion, 328th Regiment, 26th Yankee Division in the U.S. Third Army under the command of Lieutenant General George S. Patton. Remember in the movie Patton, when George C. Scott, as Patton, tells a meeting of incredulous generals that his Third Army could send three divisions against the German offensive (later known as the Battle of the Bulge) in 48 hours? The 26th Division was one of the three. Dad recalled that the Army was in a town that rhymed with “nylon” (which turned out to be Arlon, Belgium) when the order came. They marched into battle. That’s how the Yankee Division ended up in Wiltz.

The Battle of the Bulge, from mid-December 1944 to late January 1945, was a last ditch effort by the Germans to turn the fortunes of the war. They had initial success pushing a bulge into the Allied line and surrounding American forces in Bastogne, Belgium. It turned out to be the largest, bloodiest battle involving American troops during World War II. On the floor of the House of Commons, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill said of the Americans at the Battle of the Bulge: “They have suffered losses almost equal to those on both sides in the Battle of Gettysburg.” And: This “is undoubtedly the greatest American battle of the war, and will, I believe, be regarded as an ever famous American victory.”

My family arrived late at night in Wiltz in early September 1997. The town basically has two sections—a resort area on top of the hill with narrow streets and quaint shops and a working town down below by the river. We stayed at a hotel close to the old chateau at the very top of the hill because I had read in a guidebook that a World War II museum dedicated to the action that took place around the area was located in the chateau. The guidebook said the museum was open until mid-September each year.

The next morning while my family slept, I took the car and drove to neighboring towns to find plaques and memorials dedicated to the 26th Division. I found the village of Nothum, which today has a population of only about 150. It was in the vicinity of Nothum where my father took actions for which he would subsequently be awarded a Bronze Star. My dad lost the original citation that came with the medal but secured a replacement a few decades later. I now have that citation framed on the wall of my office. It states that he “courageously moved forward through a snow-covered area while subjected to hostile artillery, machine gun, and small arms fire, located the breaks (in communication lines linking the Command Post with Rifle companies), repaired them and successfully restored communications.”

Back in Wiltz, I roused the family, and we walked up to the museum. On the door was a sign that said: “Closed for the Season.”

We were so disappointed. We had been under the impression the museum was supposed to be open for at least another week. I went into the Wiltz tourist bureau and told the young woman behind the counter that I had come a long way to see the museum, and it was closed. She merely shrugged and said it was closed; there was nothing she could do.

Chagrined, we returned to our hotel to check out. I expressed my disappointment to the lady at the registration desk, but her lack of English made communication difficult. However, a young man, who turned out to be a co-owner of the hotel, heard the conversation and asked if he could help. He explained that since the tourist season had ended, museum officials just decided to close early.

I said that was too bad because “my dad was here during the war.”

Those words turned out to be as magical as “Open, sesame” for unsealing locked doors in a town that had a World War II tank parked in the main plaza and a monument to General Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The hotel owner said, “Your dad was here during the war?” When I confirmed, he told me to go to another hotel down the street and ask for the owner. That man was on the board of the museum, and I should tell him those same magic words.

I did as instructed. When I told him my father was with the 26th Division, the second hotel owner responded: “Oh, they liberated us the second time. Come with me.”

What he meant by “the second time” was that American soldiers had pushed the Germans out of Wiltz in September 1944 after four years of occupation. However, during the Battle of the Bulge, the German army reclaimed Wiltz. When the Germans occupied Luxembourg, they tried to make it part of Germany, outlawing anything, particularly French culture but also including religious practice, that would interfere with this goal. But by the end of the battle, the 26th Division pushed the Germans out of the area a second time.

My family was given a private, personal tour of the Wiltz World War II museum. What I remember most is the many pictures of the area showing the utter destruction the war brought to this small town. Our host explained that his mother was always grateful for the Americans, who gave the people of Wiltz back their freedom. His own grandfather had been forced into Nazi labor camps and returned from the war a broken man.

I also showed him a book I had with me that was produced at war’s end by Dad’s regiment, on the unit’s actions during the war. The owner asked if I would give it to him for the museum. I told him I would not give him the original, but would send a copy (which I did).

Following our tour of the museum, we returned to the hotel, where the owner bought us a round of Cokes and brought out his special guest book. As a resort town, Wiltz hosts many entertainers during the summer and winter seasons, and he has these celebrities sign his book when they stay at the hotel. I didn’t recognize the names, but I think they were German singers and actors.

He felt that the son of an American GI deserved to sign as well.

Then the hotel owner insisted we watch a video of a CNN International report from the mid-1990s. It was the story of an American soldier who had played the role of St. Nicholas for the children of Wiltz on December 6, 1944, after the German army was chased out the first time. Dressed in the robes of the town’s bishop and donning a fake white beard, Corporal Dick Brookins played St. Nick for the children who hadn’t had a holiday in years, dispensing candy contributed by American soldiers.

Decades later, Brookins was contacted by residents of Wiltz, including the hotel owner, and asked to come back and play the role again. They had not forgotten America’s generosity. Every year they celebrated the man they called the American St. Nick, and he was on hand for those celebrations a number of times. This CNN tape showed the 50th anniversary of the event, with Brookins dressed once again as St. Nick, arriving by helicopter.

I think the hotel owner showed us the tape because he was proud of his involvement in bringing the American St. Nick back and wanted to make sure we felt the gratitude the residents of Wiltz had for Americans. We were representing America that day even though we hadn’t personally fought there. I marveled that they had been able to track down the soldier, and at how strongly they felt about getting back their freedom, even so many years later. Brookins himself expressed something similar in a CNN report from 2009 that I later found online, which chronicled his return for the 65th anniversary: “I had no idea that 65 years later these people would still be trying to express their gratitude for what had happened. I am proud of that.”

The hotel owner introduced us to all the regulars in his barroom that day. We were received with strong handshakes and warm smiles. I never anticipated the kind of heartwarming welcome we received or that we would have conversations with locals about the war. I remember one older gentleman was about to leave when he was told we were Americans. He made a point to say hello and take our hands in his.

When we got back to the United States, we told my dad the story. My wife remembers he was quiet and very reflective, asking a few questions. Had he been in Wiltz, had he changed his mind about returning, and gone back and been involved in the scene at the bar, I suspect he would have been humbled, and his eyes would have become moist. I know mine are when I tell the story.

Send A Letter To the Editors