I grew up in India from the age of 4 to 14. Every two years, my family traveled back to the States on “home leave.” Via Europe or through Hong Kong and Japan, we’d head across the oceans to visit our cousins in New York and our grandparents in Massachusetts and New Hampshire.

Curious relatives and friends back home would ask: Do you speak Hindu? (The language is Hindi.) Do you know snake charmers? (No, but we see many on the streets, and they perform at birthday parties along with other performers like dancing bears and flip-jumping monkeys.) Have you seen the Taj Mahal? (Yes, it’s hard to miss.) Have you ridden an elephant? (Yes, and camels too; but camels drool and growl.)

Curious relatives and friends back home would ask: Do you speak Hindu? (The language is Hindi.) Do you know snake charmers? (No, but we see many on the streets, and they perform at birthday parties along with other performers like dancing bears and flip-jumping monkeys.) Have you seen the Taj Mahal? (Yes, it’s hard to miss.) Have you ridden an elephant? (Yes, and camels too; but camels drool and growl.)

Americans weren’t the only ones brimming with questions. Whenever I returned from the States, Indian acquaintances asked: Where is New England? What religion are you? (My family is third-generation Unitarian.) Is your father rich? (This is complicated … by Maharajah standards? By slum standards? We were certainly privileged, but more so in terms of housing and travel than money.)

Seeming exotic to natives of both countries meant that I had a lot of time to think about what an American is, and how others see Americans. It readied me—and my parents—for a life of questions.

My dad and mom were adventuresome and curious. They first moved our family overseas in 1950 to France. My father was on a visiting professorship in Strasbourg through the Fulbright program, while my mother, my sister, and I lived in Paris due to political unrest in Strasbourg. My parents jumped at the chance to go to Madras (now known as Chennai) in 1952, when my father was offered a post as cultural affairs officer for the United States Information Service (USIS), an agency meant to introduce the U.S. to the host country. Two years later, we all moved to New Delhi when my father joined the Ford Foundation as an education specialist.

Our life in Delhi was normal to us, but hardly a normal American life. We had a houseful of servants, and others (a tailor, clothes washer, and night watchman) who came in to do their work on a regular basis. My mom—a trained ballet dancer—set up a dance school in New Delhi and served as hostess for hundreds of visitors a year: diplomats, artists, businessmen, and even athletes from around the world—and from the neighborhood.

I attended a Catholic day school in Madras, then went to the American International School in Delhi through ninth grade. While my older sister Betsy went to boarding school in the Himalayas, staying in the bustling city had great appeal since I was an avid dancer—trained by my mom and a Broadway show dancer, Richard, who took over her school in later years. I also studied Bharatnatyam (traditional Indian dance) at the well-known Treveni Kala Sangam arts center in Delhi.

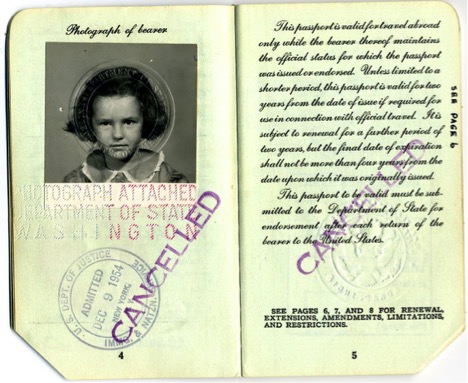

The author’s passport

The American International School was housed in old Indian Army barracks and attracted not only American kids whose families spent two-year diplomatic stints in India, but also a mix of Indian, Canadian, Vietnamese, German, Swedish, British, and Dutch kids. From these classmates and my teachers, new words not often used in the American lexicon took their place in my speech: “lorries” for trucks, “frocks” for dresses, and “full-stops” for periods at the end of sentences. Instead of American history, we studied Asian and world history. We could draw any mountain range on the Asian, African, or European continents, but the Rockies or the Appalachians? Not so much.

I loved the stories from the more recent American arrivals about life back home—they regaled us with tales of Dairy Queens, sock hops, and basketball games (we simulated, at their direction, a cheerleading squad decked out with short swing skirts and pom-poms). To keep up with our beloved but not-so-well-known America, we listened obsessively to Voice of America radio transmissions and Radio Ceylon, which had a dedications show. Young lovers could profess their devotion by dedicating songs to each other by Ricky Nelson, Elvis, and others. And boy, did we make sure we knew how to twist.

My parents’ orbit not only drew us into embassy softball games; we also got a close-up view of presidential visits to India. My parents were on duty when Eisenhower, Nixon, and Kennedy came through. I remember bursting with pride as I waved “I like IKE” posters, and my heart pounded when we all recited the Pledge of Allegiance together, always ending with “and I pledge respect to the country of which I am a guest.” (I only found out when I returned to the U.S. that schoolchildren in America didn’t say this, too.)

My parents were fiercely loyal Americans, and they wanted us to display the kinds of American values they thought were truly important. The book The Ugly American was published while we were in India, propagating the notion of loud, bullying, materialistic, and power-obsessed Americans traipsing around the world. My parents felt the burden not to validate the stereotype. We were not to speak too loudly or run through airports and public spaces like hooligans. We absolutely were not to chew gum. We worked at being gracious hosts. We were not to be profligate or showy, but we were to be always well dressed and ready to perform as “little ambassadors.” My parents were pretty good models—honest, fair, welcoming of cultural differences; very flexible about trying new foods and unfamiliar modes of travel; and amused by the vagaries of schedule (“maybe tomorrow madam”) and climate (monsoons).

They patiently fielded a slew of questions about U.S. actions around the world, and the seeming contradictions of American beliefs at home in that historical moment. How could a country have such terrible race riots and visible class discrimination despite a Constitution professing liberty and equality?

We left India for good in 1963 and landed in New London, New Hampshire, just before my sophomore year of high school. I remember thinking everything was big: buildings, roads, cars, people. And everything worked—the post office, the bank, the phones, the coin-operated Coke machines. I was so excited to come “home” to America, but I was different, and as a teenager, it was painfully evident. I wore white loafers and thin cotton clothing that seemed foreign, and I did not know the first thing about skiing. I didn’t know quite what to say when a well-meaning geography teacher announced to the class that I must have meant Indiana when I said I had come from India. Luckily the high school was flexible enough to allow me to recalibrate—I was able to take advanced French with the juniors, not-so-advanced math with the freshmen, and to my great delight, my first in-school course in American history.

What I remember most about my introduction to American history was how long the teacher focused on the colonial period. When we finally “moved west,” the school year was almost over. It reinforced my notion of just how huge America was. I knew a lot more about World War I and World War II from studying overseas, but was shy to share much about Europe and Asia when I first arrived in New Hampshire.

My parents sensed how homesick I was for Delhi—partly because the climate was so cold that I could never warm up, and partly because I didn’t like being the “new kid” in a small town. Knowing I loved to dance, they went out to find just the right present that might help with the transition. They nailed it—a tiny manual record player with a short stack of 45s, one by Chubby Checker. I must have played “Twist Again” 3 million times, and I’m sure I danced up a sweat.

Living abroad made me a lifelong appreciative observer of American life, taking nothing for granted, admiring the country’s bedrock principles and wrestling with its inconsistencies and ambiguities when the American promise isn’t fulfilled. I remain a natural global nomad, still eager to learn about other lands, but nothing touches me more than when I come back and go through Customs and the officer says, “Welcome home.”

Send A Letter To the Editors