At the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, Bob Dylan plugged in his electric guitar live for the first time—and an audience expecting acoustic folk songs booed through “Like a Rolling Stone.” Rock already had changed Dylan, and Dylan would go on to change rock ’n’ roll. But Dylan’s break from tradition was neither the first nor the last in rock history. In fact, Dylan’s musical revolution drew on an already long-established history of trailblazers and innovations in rock, which have made the genre itself possible.

In advance of the What It Means to Be American event “Is Rock ’n’ Roll All About Reinvention?”, we asked performers, historians, and cultural critics to tell us what they consider to be the most groundbreaking innovations in American rock ’n’ roll history.

For the first two-thirds of the 20th century, America was an apartheid nation. But there was something that didn’t obey Jim Crow laws or that foolish concept of a society that is “separate but equal”: the air.

We can’t regulate the air, and radio travels through the air.

Governments couldn’t legislate what you listened to in your home.

After dark, suddenly you could hear voices from all over the place, voices you couldn’t hear during the day. Growing up, I thought of this as magic time. You could hear WLAC in Nashville all the way from Tallahassee to the Canadian border.

Imagine you’re Bob Zimmerman, a high school kid in Hibbing, Minnesota. There isn’t a single black person in town. But at night, up in your room, you hear the music of black America on WLAC. You want to hear more and know more. And that desire eventually makes you want to become Bob Dylan.

And even earlier: Imagine you’re a black kid living in segregated St. Louis. You listen to the Grand Ole Opry on WSM out of Nashville and hear the voices of old, weird America. And so you grow up steeped in the white traditions of country music. That’s why, when you grow up and become Chuck Berry, all those great rock ’n’ roll songs have a narrative tradition borrowed from white country music.

When those different kinds of music met—country and western (white) and rhythm and blues (black)—something new was created: rock ’n’ roll.

The music provided a metaphor for society: two things kept apart and thought so different could, in fact, be joined. When joined, something better resulted. It was a kind of integration.

The walls came tumbling down. Separate was inherently unequal.

So think of radio as the most subversive medium. It played a huge and often unheralded part in igniting a social revolution. Not all walls have tumbled, of course, but we made a good start.

William McKeen is the author of eight books and the editor of four more. His most recent books are Too Old to Die Young and Homegrown in Florida. He is working on a book about the Los Angeles music world of the 1960s. He teaches at Boston University.

On August 13, 1952, an African-American singer named Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton, a Greek-American bandleader named Johnny Otis, and two white Jewish songwriters named Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller met at a Los Angeles recording studio for the session that produced the original version of “Hound Dog.” When Thornton’s blues-infused dressing-down of a no-account man was released the following year, it spent 14 weeks on Billboard’s rhythm and blues chart, seven of them at number one.

“Hound Dog,” an iconic rock ’n’ roll song, is the product of the kinds of interracial collaborations and cross-racial borrowings that have underwritten the genre’s history. The first hit for Leiber and Stoller, it paved the way for them to write classics that include “Jailhouse Rock,” “Yakety Yak,” and “Smokey Joe’s Café,” which sealed the team’s place among rock ’n’ roll’s most important songwriters. In 1956, “Hound Dog” became a hit for Elvis Presley. Reinventing Thornton’s song, Presley dropped the blues double entendres and the lacerating female perspective, but borrowed Thornton’s husky snarl and vocal swagger. Speeded up into a kinetic froth, “Hound Dog” went to number one on Billboard’s rhythm and blues, country, and pop charts, catapulting Presley to superstardom.

“Hound Dog” also epitomizes the fraught experience of African-Americans in rock ’n’ roll. Thornton and most of the black artists who provided the music’s foundation enjoyed less chart success and public recognition than the white musicians who worked with them and borrowed from them. During the 1960s and 1970s, Big Mama Thornton worked the blues and rhythm and blues revival circuits, inspiring Janis Joplin, who recorded Thornton’s composition “Ball ’n’ Chain,” along the way. Thornton always claimed her role as the originator of “Hound Dog.” She viewed it as her song, and the vocal power and attitude she brought to its innovative performance resound in rock ’n’ roll.

Maureen Mahon is an associate professor in the department of music at New York University. She is the author of Right To Rock: The Black Rock Coalition and the Cultural Politics of Race (Duke University Press, 2004), and is at work on a new book, Beyond Brown Sugar: Voices of African American Women in Rock and Roll, 1953-1984.

There must be 50 ways to leave your lover and at least that many groundbreaking innovations that have made rock as we know it possible. Rock’s very existence has been marked by technological inventions, cultural changes, and creative initiatives.

Some of those changes were essential for the development of rock itself, such as racial mixing, the advent of teenagers as a cultural force, and the invention of the electric guitar. Others were pivotal for certain styles of rock. Would psychedelia have been created without multi-track recording studios and LSD? Without Marshall and Fender amps, could that paean to loudness—heavy metal—have been devised? Had Bob Dylan with his wide-ranging themes not plugged in, would rock lyrics have been confined to “I wanna hold your hand”-type saccharine themes of juvenile romance?

By 1980, Sony’s invention of the CD digitized music, and allowed the record industry to recover from a financial slump and soar to higher and higher profits, reaching a peak as the 20th century ended. At the same time, another ingenious innovation, MP3s, began to replace CDs, permitting rock to colonize the Internet and shatter the record industry’s business model. Major record labels put their promotion budgets behind pop acts, reissued expensive box sets of old bands, and demanded rock bands to give them a portion of their earnings from concerts and merchandise sales. But the new digital technology also allowed bands to record their music on the cheap and distribute it online for nearly nothing, on indie labels or without any label help. Rock is thriving and innovating today, but in a very different way than it had in the prior century. Its sound has remained open to influence from every direction, which is why it is always changing.

Deena Weinstein, professor of sociology at DePaul University, has published books and journal and magazine articles on rock and has taught a sociology of rock course for several decades. Her books include Heavy Metal: The Music and its Culture (DaCapo, 2000) and Rock’n America: A Social and Cultural History (University of Toronto Press, 2015).

Without question, the electric guitar is generally understood as the first groundbreaking technological innovation of rock ’n’ roll music. Previously, the trumpet, saxophone, and piano were the instruments jazz musicians used most often for soloing over an ensemble. At the close of World War II, however, the guitar soon became central to the style of music that evolved into rock ’n’ roll for several reasons: 1) It was used in folk-like, working-class music styles such as country and blues. 2) Vocalists playing guitar could front the band. 3) The guitar was embraced by young musicians as something of their own because it was less associated with jazz music. 4) The electric guitar offered something sonically different: electronic effects.

Rock ’n’ roll’s birth was also shaped by 1940s jump bands, which consisted of a vocalist who played saxophone or piano, and who was accompanied by trumpet, piano, bass, and drums. Quintet or sextet jump bands, such as Louis Jordan and His Tympany 5, were more flexible than traditional big bands, allowing more improvisations between the lead vocalist and the rest of the band. The lyrics of jump bands’ music also spoke to everyday people—especially young people—more than traditional jazz.

These innovations coincided with American society redefining itself after World War II. Social and cultural mores concerning the way black and white people related to one another shifted. With a greater acceptance of black culture during the Harlem Renaissance in the ’20s and ’30s, a heightened awareness of black consciousness surfaced by World War II. During the 1940s, late-night radio shows hosted by hip white disc jockeys—such as Bill Allen (a.k.a. Hoss Allen) at WLAC in Nashville—broadcasted black rhythm and blues songs to curious white teenagers. This cultural revolution became perhaps the most significant innovation that led to rock ’n’ roll music.

Stan Breckenridge is a professional musician, United States Distinguished Chair Fulbright Scholar, and author. He has authored three university-level textbooks, recorded nine albums, and has lectured and performed internationally.

There are many innovations in rock ’n’ roll history—it’s a music that gives voice to loud, creative outsiders who don’t like to color inside the lines.

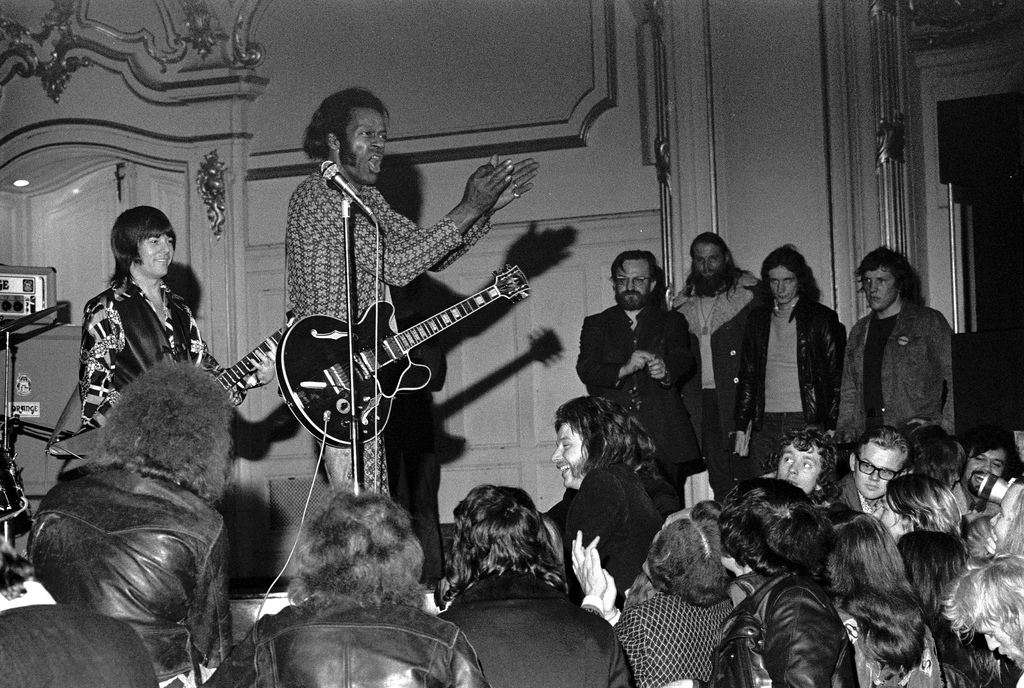

Rock ’n’ roll helped usher in the civil rights movement and an era of desegregation in American life. In the 1950s, artists like Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and Fats Domino weren’t performing protest songs like “We Shall Overcome” or “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize.” But they were attracting large audiences of both black and white listeners to hear their driving, exciting music at a time when segregation was not only legal but fiercely and violently enforced.

These performers’ passion and their music’s powerful originality made a lie of the idea that African-Americans were not full citizens. Black artists were creating a new kind of audience where black and white kids could come together. And as those kids danced, they conjured up a new, more free and open America. Ultimately, rock ’n’ roll’s most important innovation is the way it inspires us to create new identities for ourselves and our communities. Its spirit comes from young people with fresh and sometimes unsettling ideas that push us all toward reinvention if we keep our minds open.

Lauren Onkey is vice president of education and public programs at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, where she oversees award-winning educational programs for children and adults. She has published numerous essays on popular music and regular teaches university-level courses on the history of rock and roll.