When I was 9 my father, Jacob, uprooted me from my magical boyhood in Detroit to chase ghosts down historic Route 66. We were bound for L.A.

Like Dust Bowl Okies, the entire family—my parents, two sisters, and I—piled into a hapless 1960 American Motors Rambler crammed to the gills with our ragged possessions. The quest took us a month because the car kept breaking down. I spent a lot of time by the side of the road on Route 66, pouting about leaving my friends behind. I didn’t appreciate the journey at the time nor the heartstring that tugged my father across America.

Like Dust Bowl Okies, the entire family—my parents, two sisters, and I—piled into a hapless 1960 American Motors Rambler crammed to the gills with our ragged possessions. The quest took us a month because the car kept breaking down. I spent a lot of time by the side of the road on Route 66, pouting about leaving my friends behind. I didn’t appreciate the journey at the time nor the heartstring that tugged my father across America.

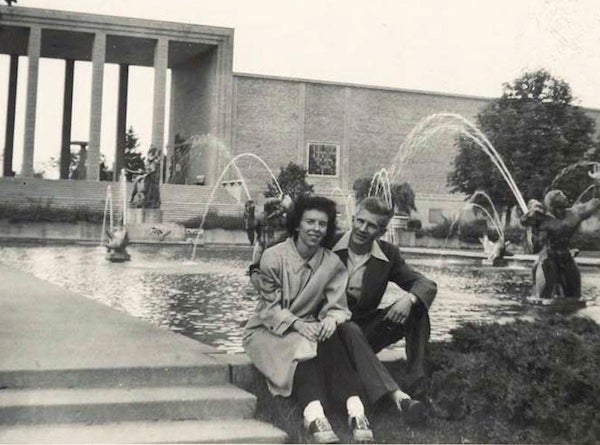

A German Holocaust survivor, he had only one immediate family member who survived World War II: a sister, Freda, who lived in Hollywood. His parents and brother died in Treblinka, the extermination camp in Poland.

In pre-Skype 1963, if you wanted to embrace family, you did it in person. So we drove.

My dad drove in near silence, oblivious to the cacophony generated by me and my squabbling sisters Fawn and Laurel, ages 4 and 12; my referee mother who tried to distract us with bologna sandwiches, games, and songs; and my dog, Beauty, who reluctantly gave birth en route to three whimpering newborn puppies who were tucked in a cardboard box in the backseat.

“Hey! How come I didn’t see the Studebaker?” I challenged Laurel as we played car bingo.

“Cuz you have terrible eyesight—you’re as blind as the puppies,” my older sister smirked. She cheated with impunity only to be dealt retribution when the dog threw up on her just before we suffered another flat tire in Texas.

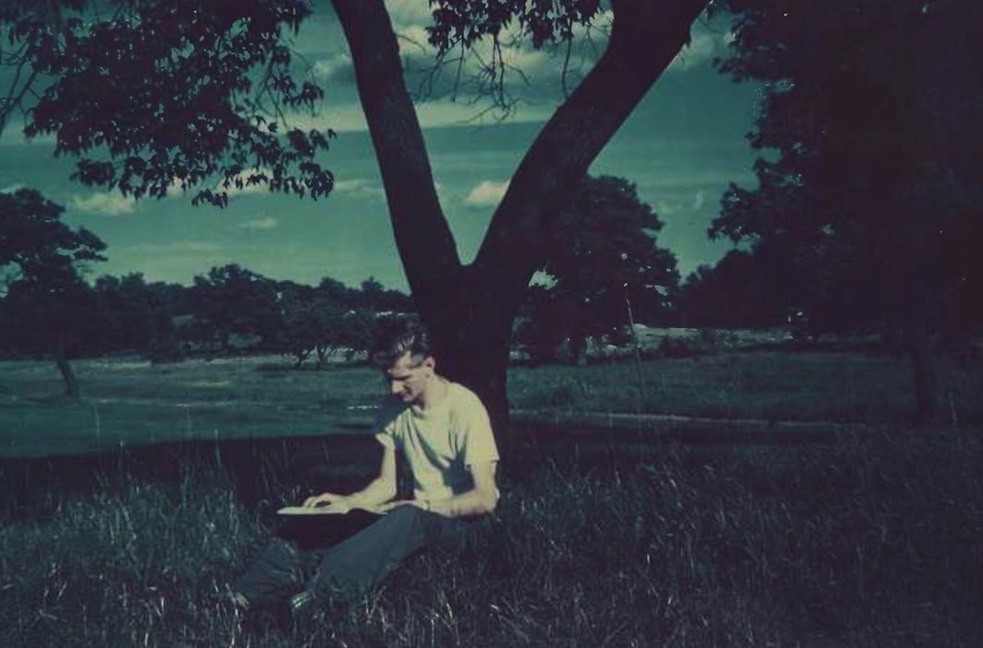

Through all this, my father somehow found solace on the road. He could be alone with his thoughts and his grief while driving. Since arriving to America in 1937, he’d marveled at the country’s wide-open spaces. After joining the Army in 1943, he hopped on a bus out of boot camp in Arkansas whenever he got leave.

My father spoke rarely, mumbling softly in German in words I didn’t understand. But he wasn’t talking to me. The ghosts of his parents and younger brother had hitched a ride with us, and Dad played tour guide for 2,500 miles across America’s heartland, sharing his awe of his new home. They bunked with us in an endless series of family motels like the Cactus Motor Lodge in Tucumcari, New Mexico, distinguished from the rest because it had a pool.

My mother Arline, a schoolteacher, wanted me to jot down everything I saw and felt on the postcards I collected of the places we stayed. “You’ll look upon it years later and discover a snapshot in time better than any Brownie Fiesta camera could take,” she said. (I recently found the postcards again in a yellowing scrapbook that had hibernated in my parents’ garage for half a century.)

So I wrote about frolicking in Buckingham Fountain in Chicago, wading across the muddy Mississippi River in Missouri, whispering like the wind through Kansas wheat fields, inhaling the red dirt and oil-scented air in Oklahoma, and idling on the trunk of the panting Rambler drinking Dr. Pepper in Texas as my father let the overheated engine cool.

I also pressed into the recesses of my mind and soul indelible images of having a family picnic in a park in New Mexico on a hot, sweltering day; meeting a lonely girl my age who had no one to play with until our brood landed for an extended spell while the Rambler was fitted with a new muffler in the Land of Enchantment; my dad gingerly lighting off firecrackers in the Arizona desert while my sisters and I waved sparklers under a canopy of shimmering stars; and a smothering dust storm that greeted us at the border of California.

“Don’t be afraid, Boychik, we’ll get through this,” my father reached over his seat and lovingly brushed my cheek. He promised me I’d appreciate the journey once we arrived at the doorstep of the Pacific Ocean in Santa Monica. “Not too many people get to do this,” he smiled ruefully.

Indeed, Route 66—commonly known as the “Main Street of America” or the “Mother Road” —had a short-lived heyday from 1926 until 1985. Before its debut, trains were the preferred mode of travel cross-country. Then, the completion of the Interstate highway system eclipsed it. Today, the world jets across America.

But my father took his time. He had no job prospects, nor did my mother. For six weeks, the five of us camped in a rundown motel in Culver City by the old Hal Roach Studios where they filmed the Our Gang Comedy series. My mother cooked meals on a hot plate. I made friends with Jorge, a Mexican-American boy, the first Latino I ever met. We shared my first cigarette. And one by one, we gave away the puppies and Beauty as our money ran thin.

My dad struggled to find decent paying work as a skilled optician in a non-union town. My mother took a job as a sales lady at the May Company before eventually getting a permanent position as an elementary school teacher. I actually made the family’s first money—a quarter—helping an elderly lady carry her grocery bags home. My folks trusted her and me in the City of Angels, innocence long since abandoned by the wayside along with many of the remnants of Route 66.

Still, in between the hustling, my family discovered the fun of Disneyland, Pacific Ocean Park right before it closed, the Hollywood Bowl, and oranges.

Sometimes, Aunt Freda came with us on our adventures in the City of Angels. To me, she was formal. But she and my dad talked for hours in German and Yiddish, sharing laughter and fond memories of their pious Jewish upbringing in Berlin before Hitler came to power. She continued to call him “Boobie,” a childhood nickname.

Likewise, my father affectionately called me Boychik. Once he mused: “I’m showing you the world near and far, Boychik. Someday you’ll thank me for this.”

I never did thank him while he lived, but beyond the pale of my boyhood, I now realize the journey was the seminal moment of my life. I left moribund Detroit for a new city that was just coming into its own in 1963. And that move afforded me education and career opportunities and love I never would have realized had we stayed.

In my scrapbook, I often described the Route 66 adventures and kitsch tourist sights as “fun.” But I know it wasn’t fun for my father and mother. They rolled the dice with everything on the line.

A few months ago I took my teenage son William to the Route 66 exhibition at the Autry Museum, not too far from our home in Los Angeles. Just before the museum exit, my fellow travelers and I were beckoned to jot down on a Post-It our thoughts and place them on a commemorative board.

“Thank you, Dad, for the experience,” I wrote simply. “Thank you for letting me follow your heart.”

Send A Letter To the Editors