What is slavery, and what does it have to do with America today?

Most people in the U.S. understand that slavery was the condition black people were forced into before the end of the Civil War. That’s entirely understandable: The United States became the largest slave society in the Atlantic World in the mid-19th century, and those bonded men, women, and children were of African descent. Indeed, I first heard of slavery from my mother’s stories of the brutality her ancestors suffered on the land she grew up on—and we visited often when I was a child—in rural South Carolina. Colonial and antebellum slavery was a shameful episode in this nation’s history, one that most Americans rather not focus on, preferring instead to celebrate this year the 150th anniversary of the end of that institution via the ratification of the 13th Amendment.

The horror of nine black men and women recently killed while holding prayer service at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston by a man who steeped himself in a racist ideology driven by a pro-slavery philosophy from the 18th and 19th centuries, however, has brought to a screeching halt our celebrations of the “end to slavery.” Instead, the nation is deeply entrenched in a debate regarding the public display and commemoration of one of slavery’s most potent symbols, and one of the accused Charleston murder’s chosen personal icons: the Confederate flag.

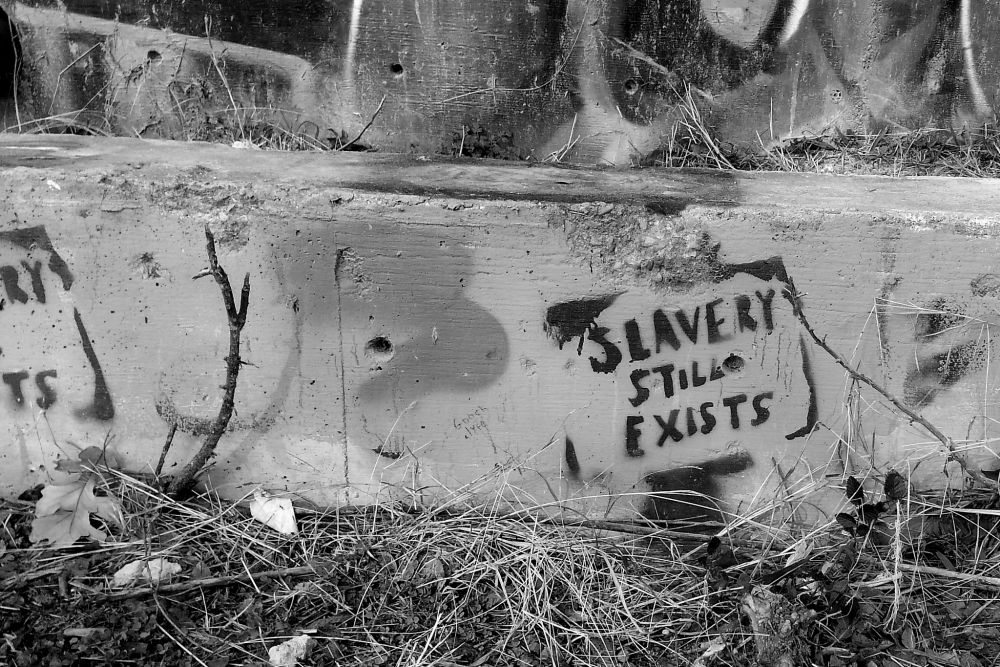

What most of us should realize, however, is that beyond these kinds of symbols, the racial mistrust and misunderstandings that linger, and the inequalities—institutionalized and customary—that never completely disappeared after black emancipation, the phenomenon of slavery itself literally is still with us. Slavery—the physical and fiscal ownership of one human being by another—is one of the most common behaviors in our global history. Almost every civilization around the world has practiced some form of slavery, from antiquity through the modern era. American slavery is not simply a relic of one particular time and place, but part of a global continuum that extends from the ancient world—where societies from Egypt and Rome to Greece and Asia had slaves—to modern times.

The early slaves could be spoils of war, but some also inherited their status. Many were kidnapped or purchased from traders. Still others were debtors or the orphaned, abandoned, or sold children of impoverished families. They didn’t just work in the domestic sphere, but were court administrators, soldiers, merchants, miners, craftsmen, agricultural workers and supervisors, musicians, and human carriers. Female slaves also served as water carriers, midwives, and healers, as well as concubines and sex slaves. Some form of slavery also existed in what would become the United States among American Indian nations, many of whom acquired slaves through slave raids or took them as prisoners of war.

Approaching slavery from such a global angle makes it easier to see the institution’s persistence around the world today, as a $32-billion-per-year industry that enslaves an estimated 20 to 30 million people. They are movable pieces of chattel (property), debt peons, sexual slaves, and forced laborers. They come from, and are enslaved in, both poor and wealthy nations (including the United States), although the poor and politically dispossessed make up the majority of the enslaved. So, too, do women and children. While most human trafficking is illegal, the social, economic, and political marginality of its victims, and the wealth and power of its benefactors, keep local, national and international authorities suspiciously inept in eradicating the problem. But these are not the only obstacles.

War—some of it fueled by cultural difference, particularly religion—and slavery often go hand in hand, making it difficult for police and government agencies to allocate the resources necessary to consistently and comprehensively tackle the issue. In the last decade, for example, conflicts in Syria, Iraq, Sudan, Nigeria, and other places have resulted in thousands of women and children being kidnapped and forced into sexual and domestic slavery. We see some of this in headlines, such as the kidnappings and subsequent enslavement of female students in Nigeria by Boko Haram. Military conflict also has thrown tens of thousands of male and female children and adolescents into the position of bonded soldiers in war-torn parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Just the other week, headlines indicated that while some of the girls kidnapped by Boko Haram over the years have been rescued, others have been forced to become soldiers.

Like war, poverty and social marginalization create populations quite vulnerable to enslavement. Each year millions of impoverished men, women, and children in South and East Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean are forced into slave labor in their home countries and in Western countries where they are brought to serve.

But what do these forms of slavery look and feel like? We have some accounts, thanks to a few brave survivors. The female author and antislavery activist Mende Nazer and an adolescent boy only known as Majok, for example, have both testified to their capture, rape, and forced labor in Sudan, where it is estimated that as many as 200,000 have been enslaved. In war-ravaged Afghanistan, an illegal tradition of kidnapping adolescent boys, such as Fahrad, who was 13 at the time his neighbor tricked him away from his home and held him captive for five months, exploits these youth as sex slaves (“bachi baza”) for powerful men.

If you live in a large U.S. city, you probably have come across these desperate people, who appear to us as low-ranking, foreign-born workers in restaurant kitchens or nail salons, as domestic workers, and as prostitutes. But they are trapped—sometimes even sold by people they know and love—and are under the near-complete control of those for whom they work. On the floor of the United Nations, Kikka Cerpa, for example, told the story of how her boyfriend tricked her into leaving her home in Venezuela to work in New York City in the early 1990s. Kikka believed she was going to be a nanny, but ended up being beaten, raped, and forced into prostitution in order to pay off her boyfriend’s bills. A “customer” promised to help her to escape, but instead held her as his own sex and domestic slave for 10 years.

No one will go on record supporting slavery, yet no one has been able to stop it either. Human trafficking legislation and activism around the world, including in the U.S., have had little success. The anniversary of the end of the U.S. Civil War, and with it, the end of some forms of slavery in our nation, certainly is worthy of celebration. But we also need to recognize that eradicating every form of slavery, here and abroad, should be essential to our moral, economic, and political agendas as a nation and as part of a global community. Eradicating generations’ old symbols is just one piece of the task, a very tiny piece of an enormous and complicated task.

Send A Letter To the Editors