These are the three things I knew about Salinas, California, growing up an hour north in the Silicon Valley: gangs, John Steinbeck, and agriculture.

Steinbeck was often required reading in California schools. But I never made the connection between the fields of lettuce and strawberries I read about in his books and the food I ate. Nor were the people who picked the food, many of them immigrant and Latino, part of my consciousness, even though my mother and her siblings had made sacrifices to come from South America to live in this country.

I first came to Salinas in 2010 after spending two years reporting on the border with the Minutemen Civil Defense Corps for my first documentary film, On the Line. My next project would be the flipside: telling the stories of Latino immigrants. I wanted to explore what it meant to be Latino in America, to work to fulfill dreams when the odds are so often stacked against you. I wanted to help deconstruct popular perceptions of Latinos and reframe the commonplace Latino narrative.

No matter how much I’ve wanted my work to “not be personal,” it has always ended up being about my experience as a Latino or my mother’s as a South American immigrant. My own identity has often been conflicted and fluid. And so my exploration of what it means to be Latino in the United States, personally and politically, has proven to be an integral part of my professional and creative journey.

As I researched Latino immigrant communities, I thought of my godmother, my Tia (Aunt). About 16 years ago, she moved to Salinas from the Silicon Valley, and I had visited her there often. I quickly learned there was much more to this community than the very negative stories about gang violence and poverty in the mainstream media.

About five years ago, with some initial funding from my university, I set off on a journey to explore Salinas as a filmmaker and journalist. I soon realized that if I made a documentary, it would have to focus on the East Salinas neighborhood known as Alisal. Alisal is 92 percent Latino, with a per capita annual income of $11,917. It’s a young community: 37 percent of its residents are under the age of 18. Only 4 percent are over 65.

Alisal, which is separated from the rest of Salinas by the 101 Freeway, was once known as “Little Oklahoma” because of all the Dust Bowl refugees who settled there. From the 1940s to the 1960s, more than 4 million Mexican farm workers came to work in the fields in the United States under the Bracero labor program, and many settled in “The Alisal,” which had been renamed in the 1930s. It was annexed to the City of Salinas in 1963.

I quickly discovered that Salinas can’t be defined by gangs (there are only maybe 3,000 gang members in a city of 155,000). The place is truly distinguished by high levels of devotion of people to their neighborhoods and their families. And what really defines the place is the sheer difficulty of the work people do there.

Picking food in the fields is quite literally “backbreaking.” Most long-time pickers injure their backs severely. And because many workers are undocumented, there is little in terms of disability services.

That backbreaking work shapes Salinas as a whole. Many of the young people I met work in the service industry—restaurants, retail, cleaning—while their parents work in the fields. Those young people who don’t have financial support and don’t qualify for financial aid for college end up continuing in the service industry or going to work in the fields like their parents. Gangs specifically target the Alisal neighborhood for recruitment because parents working long shifts in the fields and holding down multiple jobs are often not home to supervise their children.

Alisal also stands out for its high-density housing. As you drive around the neighborhood, Alisal you see garages with messy foam insulation outlining the garage doors. These are converted garages, where families, sometimes multiple families, live, with questionable electricity and water.

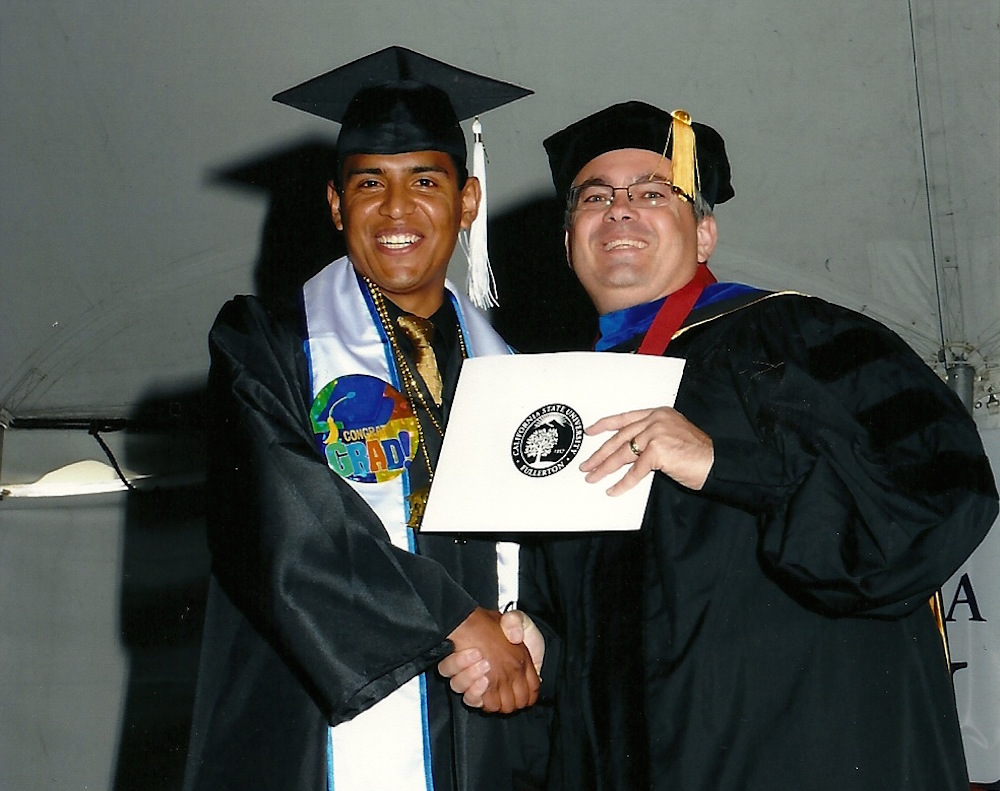

In Alisal, I met four young people who became the focus of my documentary, which came to be called The Salinas Project. Yajaira, Fernanda, Angel, and Lolo range in age from 18 to 27. They were primarily raised by single mothers who worked in agriculture. Both young men had brothers murdered in gang violence.

Reporting in Salinas came with big challenges. The first was gaining the trust of the young people I would profile. The young women welcomed me with warmth and honesty. With the young men, trust-building proved more difficult. Tracking down Salinas young people, who would move often and change their cell phones, was another major challenge.

One young woman featured in my documentary, Yajaira, was especially important to my work. I met her shortly before she graduated from Alisal High School and three days after her 18th birthday. Yajaira would be starting college in just a few months on a full scholarship. She worked nights at KFC to help support her family; her mother was no longer working in the fields after being injured on the job. For our first on-camera interview, Yajaira invited us to her home—a garage she shared with her brothers and mother. The garage was rented from the owners of the main house. Yajaira slept on the cement floor; she hadn’t slept in a bed in years.

Yajaira lived in the center of the Alisal, across the street from a well-known park, and she talked about the drug deals and gang murders that took place there. While my crew and I toured the park with her, we saw six men on the ground as police arrested them. Yajaira pointed out the church across the street, where her family stayed a few years back when they were homeless and had nowhere to go.

Yajaira was open about her suffering—it was part of what made her a fighter, a hard worker, and an honors student. Yajaira was also a community activist who worked with Building Health Communities. She told me she was planning on finishing college early and going on to pursue a graduate degree.

I filmed a transformative, unstable period in Yajaira’s life over several years. Her mother, who went back to Mexico to try and gain documentation, got stuck there, and was unable to return. Her little brother, who first went to Mexico with her Mother, returned to Salinas. Yajaira’s housing situation was difficult and constantly changing. She also had some health problems her first year of college.

Yajaira from Zócalo Public Square on Vimeo.

Yajaira’s reality was so different from media representations of Salinas and its people that I started to scrutinize the local TV news. It quickly became clear that crime was as much a part of the city’s media culture as it was a part of its outside reputation. So, in 2012, I conducted a quantitative and qualitative analysis of two months of local TV news in Salinas.

The results surprised even this jaded journalist: More than 46 percent of the news stories were crime-related, Latinos were overrepresented as perpetrators while underrepresented as victims, and gang violence was featured almost daily. The TV news also asked the audience to take an active role in “catching criminals,” cultivating fear with segments like “Manhunt Monday” (which aired more than just on Mondays).

The study concluded the local media’s overemphasis on crime doesn’t just misinform and inaccurately define Salinas. It also reinforces the negative stereotypes and hateful rhetoric—of the kind we’ve seen most recently from Donald Trump—that have been part of the national immigration debate.

The Salinas Project Open/Media from Zócalo Public Square on Vimeo.

Today, after finishing The Salinas Project I find myself back in Salinas, shooting for my next film, about U.S. Latinas, titled Las Mujeres: Latina Lives, American Dreams. I’m glad to be back. My time in Salinas has been full of discovery, and I’m ready to discover even more.

I now know firsthand how hard the cycle of poverty is to break. And I’ve seen how hard most young people in Salinas must work to better themselves and their families. Cut through all the misunderstandings about life in Salinas, and you’ll find, at the heart of the city, the aspirations of its people.

Send A Letter To the Editors