The retrospective exhibition “Someday is Now,” currently on view at the Pasadena Museum of California Art, has brought a lot of attention back to the Southern Californian artist Corita Kent. It’s a focus that hasn’t existed in the nearly three decades since her death. While many of her contemporaries have become household names—including friends and influences John Cage and Charles and Ray Eames—Corita Kent hasn’t reached a posthumous level of fame on par with her artistic achievements.

By the late 1960s, Corita had exhibited work in over 230 shows across the country. She had appeared on the cover of Newsweek and in hundreds of magazine and newspaper stories. She was named a woman of the year in 1966 by the Los Angeles Times, invited to join a White House conference on education, and completed commissions for the World’s Fair, IBM, and Westinghouse. Her work was already in prestigious collections like those of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Modern Art. And yet, you’ll find her largely unmentioned in art history texts.

The canon of art history undergoes constant revision, and we are more concerned now with who is included and excluded than we were in the middle of the 20th century. Still, Corita seems to have been victim of some discrimination. She was discounted as a woman (and a nun for much of her life) who was based in Los Angeles and not New York, and perhaps also because of her medium, silkscreen. Ironically, one of the most appealing aspects of her art, its availability, was probably a barrier to her being treated as a serious 20th-century “artist,” even today.

Corita began screen-printing in the early 1950s and continued with the medium as an art professor at Immaculate Heart College in Los Angeles. Her aesthetic was very different from that of religious art of the 1950s. Figures were typically, clean, white, wearing flowing robes, and in a pastel palette. But Corita’s dark, primitive, abstracted figures were heavily influenced by medieval art, and later—as they grew brighter and incorporated populist imagery—by the rise of contemporary abstract expressionist art.

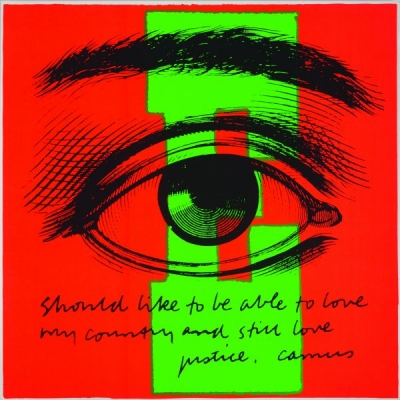

In 1954, Corita began illustrating text from the Bible and literature she liked. One of her earliest and strongest influences was E. E. Cummings. Verses of his poem “be of love (a little)” appear in her work over a dozen times. A line from one of Cummings’ lectures, “damn everything but the circus,” was incorporated into several works and even inspired an entire series of alphabet prints. Her choice of sources for text was very broad. From literature, she also cited Rilke, Gertrude Stein, Ugo Betti, Walt Whitman, Anaïs Nin, Lewis Carroll, Lorraine Hansberry, and others. She quoted the Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, and the Doors, as well as popular advertising campaigns, her brother Mark, her students, the Bhagavad-Gita, traditional Native American blessings, and finally, her own words.

In the late 1960s, Corita was exhausted by the adulation and criticism that her work inspired and by the pressures of simultaneously creating work, exhibiting, teaching, and being the face of the Catholic reformation movement. In 1968, she left the Immaculate Heart of Mary order and Los Angeles, her home for over three decades. She moved to Boston, where she continued to work until her death in 1986.

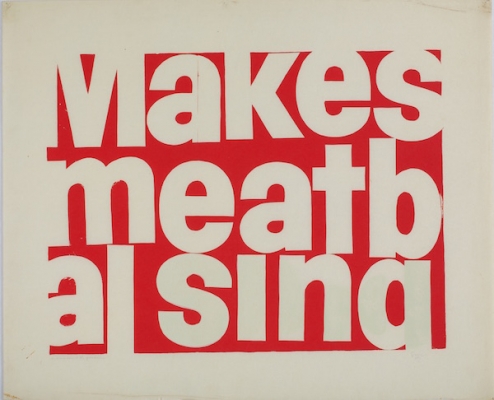

As the director of the Corita Art Center in Los Angeles, I think that one of the reasons for renewed interest in Corita’s work is the multifaceted appeal it holds to our 21st-century, split-second attention span. She took words and graphics meant to be read and understood instantly and tricked you into looking at them longer. She did this by both re-contextualizing common messages and manipulating familiar imagery. For example, song about the greatness, from 1964, reads, “makes meatbal[ls] sing” in bold white letters across a red background. While you’re trying to place that slogan (for Del Monte tomato sauce), you notice another message, almost white on white, contained in the word “sing.” It’s a passage from the Psalms about the oceans, rivers, and mountains exalting the arrival of God. Writing about this piece in 1966, Corita said, “If mountains can shout and rivers can clap their hands, then meatballs can sing.” Whether you are drawn into the bright colors, popular source material, or scrawled messages, the depth of Corita’s work holds your attention beyond whatever first caught your eye.

While her good friend Mickey Myers assures me that Corita would be “tickled” by the exhibitions of her work around the world, she never wanted to be a celebrity artist like Andy Warhol or Jeff Koons. People who knew her have repeatedly told me that, as a friend and teacher, she focused her full attention on whoever was in her presence. She incorporated her “happenings”—where participants were given props and instructions about how to interact with the people around them–into her speaking engagements. She did this, I think in part, to draw attention away from herself. This is even evidenced in her infamous massive class assignments. If your teacher asks you to make 200 drawings or stare at your arm for three hours and draw it without looking at your paper, you can’t very well pay much attention to her; you need to focus on the task at hand.

Much of Corita’s art was motivated by her commitment to messages and reaching people, but in a way that fit with her reluctance to be in the spotlight. When she was asked to speak about her activism, she mentioned her friends Dan and Phil Berrigan, who let their own blood in protest of nuclear weapons, made their own napalm to burn draft cards, and spent time in jail for both those acts and more. Corita said she wasn’t brave enough for those things, but would say what she wanted with her art.

The most important thing to understand about Corita’s work is how responsive she was as an artist to the world around her. The reforms of Vatican II, which strongly influenced Corita and her fellow sisters at IHC, were about meeting people where they were and Corita chose the symbols in her art to do that, as well. Using images people saw at the grocery store or songs they heard on the radio, her art revealed spirituality in the everyday.

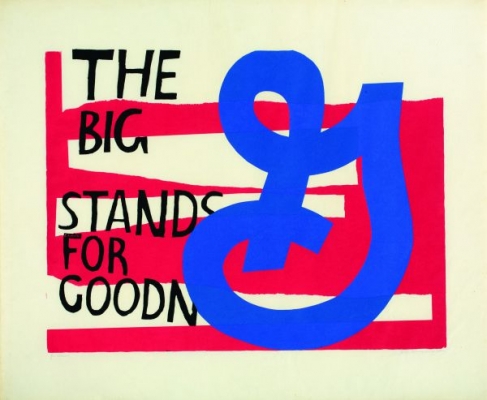

Corita said that ads and billboards were the carriers of man’s loves, hopes, and beliefs, and that she was restoring life to words by taking them back from advertising. For Corita, “the big G” wasn’t General Mills, it was God; the dots on the Wonder Bread wrapper weren’t a decorative element, they were hosts. But her work was not a commentary or criticism of mass-market commercialism, as some may read it today. Her work was about joy and, she said, giving people an idea of what harmony might look like.

In 1967, Corita said to Newsweek that “Los Angeles remains marvelously unfinished,” something that’s still true in many ways. As L.A. comes into its own as a creative city, a re-examination of its roots is warranted. Corita’s work is part of that re-examination, along with that of Mary Corse, Noah Purifoy, Carrie Mae Weems, and other artists who waited too long to receive their due.

If she were alive today, I’m sure Corita would still be an advocate for social justice and creating work with a message. I’m sure she would be delighted to communicate with people all over the world through social media. For Corita, looking was a spiritual act and she would invite you to do that: just look.

Send A Letter To the Editors