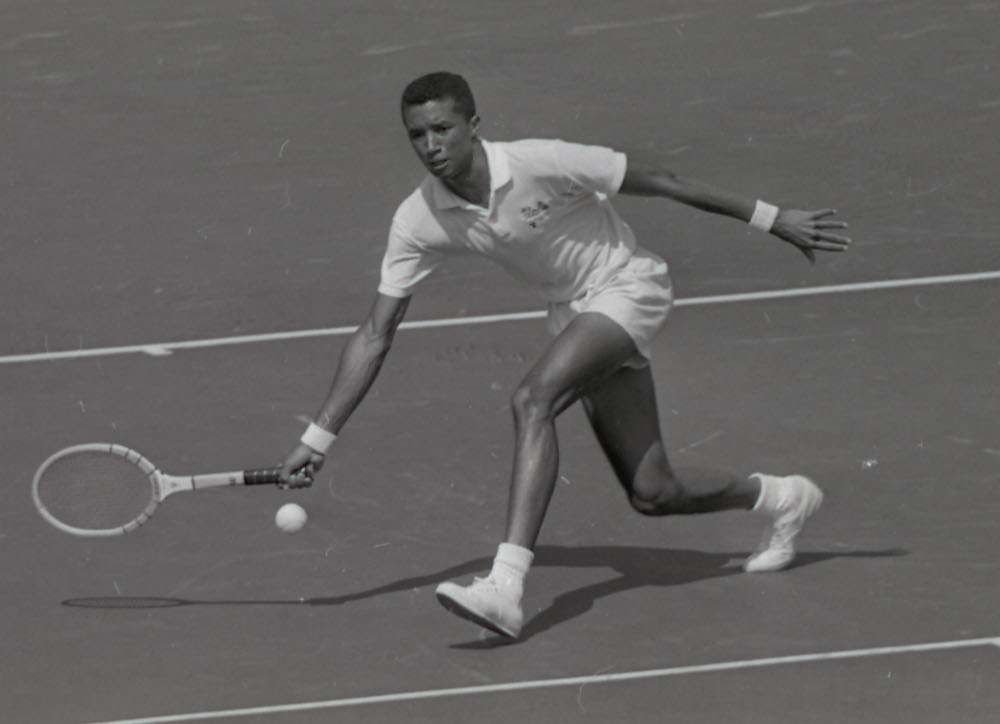

We tend to recognize heroes like Arthur Ashe in a kind of short-hand: first African-American man to win singles tennis titles at Wimbledon, the U.S. Open, and the Australian Open; first African-American to be selected to represent the U.S. at the Davis Cup; and, at the university where I teach—UCLA—one of the most famous alums, period.

We tend to recognize heroes like Arthur Ashe in a kind of short-hand: first African-American man to win singles tennis titles at Wimbledon, the U.S. Open, and the Australian Open; first African-American to be selected to represent the U.S. at the Davis Cup; and, at the university where I teach—UCLA—one of the most famous alums, period.

But these accolades aren’t the main reason I teach a seminar focusing on Ashe’s life. The trajectory of this tennis player’s life—from his birth in the Jim Crow South of the 1940s to his untimely death from AIDS in 1993—brings much of the American century to life for my students, with all the complexity that gets lost when we think of these people solely as the achiever of milestones. And, perhaps because recent history is often the most neglected history, it is also the vital missing link in explaining to my students where we’re coming from as a society, and providing them with exemplars as they face similar challenges in their lives.

Even though Ashe’s name is mentioned by every campus tour guide and promotional video of any length about UCLA, and even though students go to a wellness center named in his honor when they are sick, students were quick to admit on their first day in my class that their understanding of Ashe’s legacy was confined to a hazy notion that he was the black man who clicked off a bunch of firsts in the world of tennis. Some knew that he had died of AIDS; some knew that he was a social activist.

In my class, we start Ashe’s life journey in the 1940s, with the family home in Richmond, Virginia, where his industrious and devoted father accepted a job as caretaker for Brook Field, Richmond’s only park for negroes, in the vernacular of the day. The job, which came with a house and proximity to tennis courts, embodied the era’s “separate but equal” doctrine.

In Richmond, blacks could not say that they were denied the amenities afforded whites. Their park had a tennis court, too, although the trappings of tennis were largely unattainable to most of Richmond’s African-American community. But sports became the special lubricant—and motivator—in Ashe’s life. Young Arthur thrived by having tennis courts in his backyard and the attention of one of the only black coaches of the era, but he beat his local opponents too easily. Since the segregated school system precluded him from playing whites, his father agreed with a coach’s recommendation that his son should spend his senior year in St. Louis, where race would not restrict his range of tennis opponents.

Today, most parents are loath to move for fear of incurring the wrath of teenagers separated from their friends and the rituals of graduation. But Arthur Ashe, Sr.—Arthur’s mother had died when he was six—split up his close family of three in order to expand Arthur’s opportunities. And it worked. A stellar senior year in St. Louis positioned him for offers of tennis scholarships. Inspired by the example of Jackie Robinson and wooed by legendary tennis coach J.D. Morgan, Arthur Ashe entered UCLA in 1962.

In Ashe’s undergraduate days, the word service did not evoke SAT tutoring programs or planting community gardens. Service meant the armed forces, and male college students lived with the knowledge that they could be dispatched overseas quite readily. In addition to perfecting his tennis game and focusing on his studies, Ashe enlisted in the ROTC. This commitment required a post-graduate obligation that Ashe fulfilled at the next stop on his life journey: West Point. His superiors allowed him to advance his tennis game.

His younger brother Johnnie, on the other hand, was in Vietnam, like so many other young men of his generation. In fact, fearful that Arthur might have to do a tour of duty, Johnnie re-enlisted, making the case to his superiors that if one Ashe brother was getting his mail in Vietnam, the other should be allowed to stay stateside. Safe from enemy fire, the older brother Arthur was a second lieutenant who worked as a data analyst and tennis coach at West Point.

While Ashe was playing tennis and pursing his military obligations, other African-American young people were engaged in direct political action and at times he faced withering criticism for not joining in the struggle. Indeed he was booed at a speaking engagement Howard University because the students were incensed that he had played tennis in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Ashe’s complex relationship with South Africa would come to exemplify some of the schisms in how Americans of the civil rights era thought about racial progress. During that era, any ambitious tennis player was expected to prove his or her mettle in the prominent South African matches. Even though he was a college graduate, a prize-winning tennis player, and member of the American military, Ashe could not get a visa to play there until the 1970s. His decision to play there after he finally succeeded in obtaining a visa riled both members of South Africa’s white apartheid establishment as well as anti-apartheid activists here at home. Ashe shared their disdain for what he called “the abyss that is South African apartheid.” During the years when he transitioned from being a tennis player to being a tennis coach, he worked behind the scenes advocating that the United States exert its influence towards dismantling apartheid. When he took more public stances, such as getting arrested outside the South African Embassy in Washington in 1985, the bad publicity likely contributed to his being fired as captain of the Davis Cup team.

Unbeknownst to him, tennis fan Nelson Mandela was following his career and reading Ashe’s books in his cell on Robben Island. Upon his release, he identified Arthur Ashe as the American he most wanted to meet.

He encountered controversy again in 1992 when he announced that he had contracted HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. Ashe had become infected years earlier from blood transfusions necessitated by heart attacks at a relatively young age. But this was an era when the stigma against HIV and AIDS was severe—because it was assumed that only gay men or IV drug users got the disease. Ashe’s ability to deal with his diagnosis in private was shattered when USA Today shared with him its plans to “out” his HIV status, forcing him to announce his illness in a hastily arranged press conference. A colleague down the hall from me stopped buying that newspaper the day she heard about its role in Ashe’s life, and she still holds a grudge more than two decades later. But Ashe didn’t shy away from his association with the disease once the news became public: He was an activist to the end. Ashe dedicated himself to AIDS awareness and used his visibility to draw attention to the plight of black South Africans and Haitian refugees.

When I contemplate the character traits I want this generation of college students to embody, Ashe provides a good checklist. Not only was he a tennis star of the first order, he also wanted to help the next generation, establishing junior tennis leagues and coaching the U.S. Davis Cup team. Ashe took being a student-athlete, and not just an athlete, quite seriously throughout his life, and wanted to influence how the public looked at African-Americans. He crafted the first major study—three volumes in length—of African-American sports history. He also penned numerous op-ed essays and several other books, including his best-selling autobiography, Days of Grace. He was a shrewd businessman who knew how to take the comparatively modest tennis purses of his day and invest them prudently. He married once and well, to Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe. Once engaged in an issue, he persevered.

To be sure, much has changed since Ashe’s time: My students don’t have to worry about a military draft, and if they are so unfortunate as to be diagnosed with HIV, there are medications to extend their lives. But their times are turbulent as well; issues of race, class, war, and disease continue to shape 21st-century life. If they can learn from Ashe’s life how to sustain personal and professional integrity, how to handle setbacks with grace, and how to play the long game, they will lead lives of distinction and purpose.

Send A Letter To the Editors