Voting, James Madison once wrote, is fundamental in a constitutional republic like America. Yet “at the same time,” he noted, its “regulation” is “a task of peculiar delicacy.”

Madison was talking about whether America should restrict voting rights to property owners—but he might as well have been debating ballot selfies.

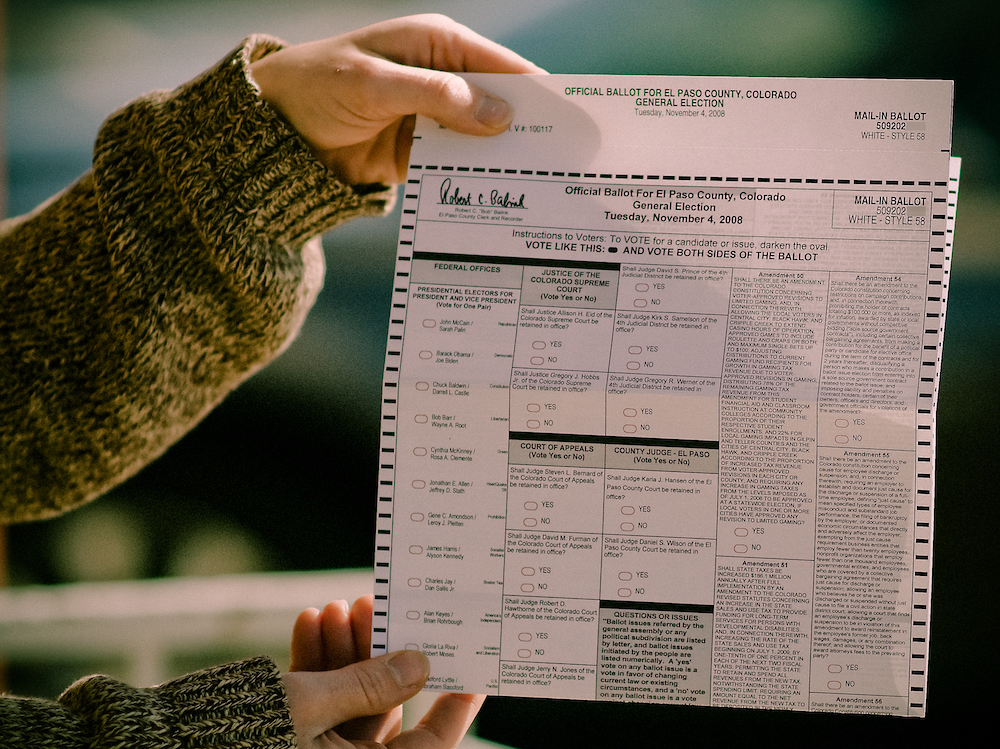

Ever since Americans began carrying smartphones with cameras, we’ve been posting photos of our ballots on social media. The so-called ballot selfie—which is not an actual selfie but typically a photo of a completed ballot—is now nearly as ubiquitous on voting day as those omnipresent stickers. It is how a great many Americans, millennials especially, convey their choice for elected office, share their voting enthusiasm, and implore their friends to follow suit.

And, in at least 25 states, it is illegal.

This widespread criminalization of ballot selfies occurred in state legislatures over many years with relatively little debate; some states simply extended existing bans on voting booth photography to cover the new genre. But the issue shot to prominence in 2014 when New Hampshire began investigating three voters who posted ballot selfies in violation of a state law that bars voters from “taking a digital image or photograph of his or her marked ballot and distributing or sharing the image via social media or by any other means.” (One voter uploaded a picture of his Republican primary ballot to Facebook with the caption: “Because all of the candidates SUCK, I did a write-in of Akira,” his recently deceased dog.) Facing impending prosecution, the voters fought back in federal court, arguing that the New Hampshire statute violated their free speech rights under the First Amendment.

In August 2015, the voters won a total victory in a strongly worded opinion by U.S. District Judge Paul Barbadoro, a George H.W. Bush appointee. Barbadoro reasoned that the New Hampshire law was a “content-based restriction on speech because it requires regulators to examine the content of the speech to determine whether it includes impermissible subject matter.” And according to the Supreme Court, when a speech regulation “target[s] speech based on its communicative content,” courts must subject it to strict scrutiny—meaning it must be narrowly tailored to further a compelling government interest.

Barbadoro found that the New Hampshire law satisfied neither prong. First, he challenged the state’s argument that the law furthered the “compelling government interest” of preventing vote-buying. New Hampshire hypothesized that vote-buyers might demand ballot selfies to ensure their money was well-spent but could not find an iota of evidence that this method of vote-purchasing actually occurred, making the threat too abstract to satisfy strict scrutiny: “For an interest to be sufficiently compelling,” the judge wrote, “the state must demonstrate that it addresses an actual problem.” Second, Barbadoro found that the law was far too broad to be narrowly tailored. “When content-based speech restrictions target vast amounts of protected political speech in an effort to address a tiny subset of speech that presents a problem,” he wrote, “the speech restriction simply cannot stand if other less restrictive alternatives exist.”

Just two months later, a federal judge in Indiana reached an identical conclusion in striking down that state’s ballot selfie ban. With some alarm, the judge noted that Indiana had criminalized political expression—thereby violating a bedrock principle of the First Amendment—in order to address an apparently nonexistent problem. Since then, New Hampshire has appealed Barbadaro’s decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. The judges’ palpable skepticism at oral arguments in September suggests the state is poised to lose unanimously.

Absent evidence of vote-buying, these ballot selfie bans do seem to be overreactions—possibly well-intentioned regulations that nevertheless foster perilous political censorship. Expressing joy or anger about an election is core political speech—where, the Supreme Court has noted, “the importance of First Amendment protections is at its zenith.” New Hampshire and 24 other states seek to suppress a mode of communication beloved by young voters with no justification other than abstract concerns over a phantom threat. The ballot selfie may be emphatically modern, but ballot selfie bans look a lot like old-fashioned censorship.

Not every election law expert agrees. Writing in Reuters, Richard Hasen insists that ballot selfies are a “threat to democracy.” Hasen asserts that vote-buying “is a real—not theoretical—problem,” and that banning ballot selfies is a narrowly tailored way to combat it. A ballot photo, he writes, “is unique in being able to prove how someone voted.” Hasen even speculates that the reason vote-buying is so rare is because of laws like New Hampshire’s. Quoting Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in a decidedly different context, Hasen proclaims that repealing ballot selfie bans because vote-buying doesn’t occur “is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

There are three problems with Hasen’s analysis. First, ballot selfies don’t irrefutably “prove how someone voted”; as election law attorney Daniel Horwitz has explained, voters using both paper and electronic ballots could almost always change their votes after snapping a photo. Second, the (still relatively rare) instances of voter fraud to which Hasen alludes likely would not have been foiled by a ballot selfie ban. Vote-buying almost always occurs through mail-in absentee ballots, not at the polls. Yet some ballot selfie bans only proscribe photographs inside the voting booth. And even broadly written bans would surely fail to stop absentee ballot–buying. If you’re selling a ballot that you fill out in the privacy of your home, you could easily prove your vote by other means—like showing it to a vote-buyer in person. (Why would you want to tout your purchased ballot on social media, anyway? That’s the least private way to prove how you voted.)

Third, and perhaps most importantly, Hasen doesn’t seem to recognize the immense value that young voters today place on ballot selfies. Millennials use ballot selfies to convey information about their political views and engage with their friends about elections, to broadcast their personal ideologies, and share excitement about voting. (And they may foster more voting: One study suggests that Facebook users are more likely to vote when their friends reveal on social media that they have voted.) No matter how many states ban them, they will remain pervasive on Election Day, a key mode of political expression for the younger set. At this point, nothing short of a heavy-handed government crackdown can reverse that. The question, then, isn’t whether states should stop ballot selfies, because they can’t. The question is whether states should dangle the threat of prosecution over voters who dare to share a picture of their ballots, chilling speech and stifling political passions.

James Madison never wrote anything about smartphones. But it’s not hard to guess where he would’ve come down on ballot selfie bans. The founding father may have called election regulation “a task of peculiar delicacy,” but his view on free speech was simpler: It shall not be abridged. For better or worse, ballot selfies have become a fundamental mode of political speech in America. The First Amendment is clear here: Let the voters Snapchat.

Send A Letter To the Editors