Vice President Mike Pence, left, and National Trade Council adviser Peter Navarro, right, wait for President Donald Trump to sign three executive orders, Monday, Jan. 23, 2017, in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington. Photo by Evan Vucci/Associated Press.

Every American knows that if you want to spend more than you earn, you either must liquidate some of your assets or you must borrow. This is as true of governments and corporations as people. And if you have been doing a lot of borrowing, stopping will result in much less consumption. Teenagers without finance PhDs learn this when their parents take away the credit card.

Which is why it boggles the mind that experts in Washington D.C., including the President’s senior economic advisor Peter Navarro, fail to understand this fundamental principle as it applies to tariffs and border taxes. Perhaps these experts think manna will fall when we execute trade policies that purport to close the trade deficit. But what they advocate—tariffs, currency adjustments, and other protectionist measures—is no different from Sisyphus pushing a rock up the hill only to have it roll back on top of him.

If you take Navarro’s argument at face value (and not as a populist diversion), Trump’s protectionists believe that by closing the trade gap and bringing manufacturing back to the U.S., we will grow and become wealthier and more prosperous. Navarro’s argument was presented in a Trump policy white paper written with Secretary of Commerce nominee Wilbur Ross, entitled “Scoring The Trump Economic Plan.”

In it they explain their position:

“Suppose the U.S. had been able to completely eliminate its roughly $500 billion 2015 trade deficit through a combination of increased exports and decreased imports rather than simply closing its borders to trade. This would have resulted in a one-time gain of 3.38 real GDP points and a real GDP growth rate that year of 5.97 percent.”

This is so far off the mark that it begs a little work explaining why. So let’s consider how (and if) one can close the trade gap with China and what the consequences would be were policy to be successful in accomplishing this.

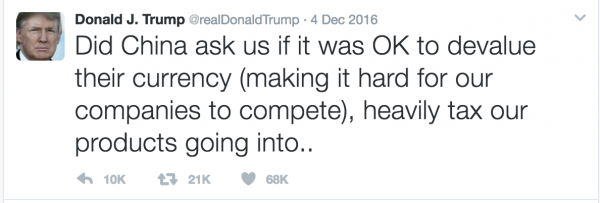

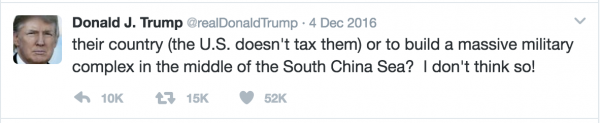

In December, Trump tweeted: “Did China ask us if it was OK to devalue their currency (making it hard for our companies to compete), heavily tax our products going into their country?… I don’t think so!”

He also has repeatedly claimed that China is a currency manipulator. So, let’s suppose he convinces China to increase the value of the yuan. (Important note: China would have to be a manipulator to do this, as most people who follow foreign exchange rates think the yuan is overvalued rather than undervalued).

Presumably a yuan of higher value would make American goods less expensive for Chinese and Chinese goods more expensive for Americans. Similarly, a tariff on Chinese goods would presumably make them more expensive, discouraging imports. But the realities of trade would complicate those plans.

China’s purchases of American goods and services are mostly airplanes, machinery, earth-moving equipment, food, scrap, and education. Will the Chinese buy more airplanes if they are less expensive? Perhaps they will buy one or two, but not much more. It is not easy to integrate new airplanes into an airline. And earth-moving equipment? That depends much more on China’s infrastructure needs—and not all that much on the price offered by Caterpillar.

Food? Yes, the Chinese will buy more food, but that in turn will drive up the price of food for Americans. And education? It’s hard to say if that would have any effect, given the scarcity of higher education here. Are there really extra spaces in U.S. colleges and universities for more Chinese students?

The point of considering all these examples is this: Chinese demand is not very sensitive to price for the goods the Chinese purchase. So it would take a very large increase in prices to bring trade back in balance from the Chinese side.

But, you might counter, couldn’t we sell consumer goods to Chinese households that they do not as yet buy? Aren’t there 1.4 billion Chinese who might like a whole host of consumer goods America could produce?

Yes, but in practice, it’s hard to get people to change their behavior. For Chinese households to buy more goods, they would have to reduce their savings. And that won’t be easy. Yes, there is room for more consumption—at present Chinese saving rates are above 30 percent, which is very high. But the ruling Communist Party has found it difficult—as demonstrated by its own failed efforts to create demand for domestic consumer goods—to get Chinese families to stop saving so much.

Why? China does not have the social safety net of the United States. So Chinese families are saving to take care of their parents, to have a decent retirement, and to pay for their child’s education—and marriage. Marriage is a critically important expenditure for many Chinese families, as the one-child policy has resulted in a shortage of women for marriage. Chinese families raising a son are saving huge amounts of money to educate their child and purchase a home for him, increasing his marriage prospects. No matter how cheap North Carolina furniture is in Shanghai, Trump is trumped by the prospect of a grandchild.

Okay, so if the Chinese are not going to buy much more even if the yuan strengthens or if prices drop, then what about the U.S. purchases of Chinese goods? Wal-Mart shelves in the U.S. are full of inexpensive goods from China that Americans purchase. And yes, were the yuan to appreciate, these goods would become more expensive and we would purchase less. But a rise in the yuan would also make textiles, toys, and electronics from Malaysia, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Bangladesh—all countries with a significantly lower cost of labor than China—more attractive. As a result, we would still not close the trade deficit—we would just make U.S. consumers pay more, to cover the costs of moving the factories out of the Pearl River Delta and into Southeast Asia.

The same effect would be produced if prices were raised on more expensive goods such as iPhones and steel. India, which could produce such items at a lower cost than China, would benefit, and China (losing factories) and the United States (paying more) would be hurt, but not much else would change.

Simply put, tariffs or currency changes are only going to produce marginal changes to the trade deficit because you cannot tweet away the fundamental problem: Americans do not save enough to pay for their expenditures.

U.S. households on average save a bit over 5.5 percent of their disposable income. Take that percentage of the economy, and add corporate savings and the amount collected in taxes, and you have approximately 18 percent of GDP that is available for investment and government spending, as opposed to consumption. Investment accounts for the bulk of that 18 percent—approximately $3.1 trillion. That leaves the rest for government.

And the rest is not nearly enough to pay for all federal purchases and transfers. In fact, the U.S. is short of the money it needs for federal spending by upwards of $400 billion a year. So where do we get that money? It comes from people who sell more than they consume—like the Chinese.

So if we didn’t have a trade deficit, we couldn’t cover our spending. We would either have to increase taxes (the Republicans who control Washington want to cut taxes), save a lot more (and how could we motivate Americans to do that?), or cut government expenditures (politically impossible).

In fact, our need for people who sell more than they consume is increasing. The federal deficit is projected to grow to $1 trillion by 2023. Someone has to cover that with saving. If not the Chinese, then who? The Russians? The Japanese? The Indians?

Remember Peter Navarro’s argument. He says that economic growth will solve our problems—and cover the deficit. So let’s do a little arithmetic to check this out. Don’t worry about the math—it’s simple.

A $1 trillion deficit is about 5.3 percent of GDP. If Trump and Navarro are going to deliver the rapid economic growth they promise, corporations will be investing their additional saving to drive that growth. So if the money to cover the trade and fiscal deficits is not going to come from foreigners it must come from household saving. And to achieve an increase of private saving of $1 trillion by 2023, GDP would need to double. That would require a sustained growth rate of 10.2 percent. Historical growth has been at 3 percent, and recent growth at 2.5 percent. It’s ludicrous to believe we will grow out of the savings gap.

Is there another way? The answer is yes. But it wouldn’t be pleasant. You could, like Argentina, raise tariffs (also called import taxes) to such an extent that imports become prohibitively expensive. Doing so would completely disrupt the globally dependent automobile, construction, computer and electronics, telecommunications, retail, and manufacturing sectors and send the economy into a tailspin.

The low savings rate on falling incomes and higher unemployment would mean the federal government would have to tighten its belt. And, as we saw in the Great Depression, households—freaked-out by the potential for horrible economic outcomes—would dramatically boost savings rates (Remember your Depression-era grandmother washing Saran Wrap so as to reuse it?). Eventually, the economy would recover, but at a very high price and at a lower level of income and wealth than would otherwise have been the case.

If we consider the trade deficit a problem (and at current levels it may well be one), then appropriate economic policy is to institute long-term reforms that boost domestic saving and reduce the federal deficit without crashing the economy. Bellicosity and tariff mongering do not constitute long-term reform. And they are an exercise in futility anyway.

Perhaps the 20th century American postmodernist John Barth said it best in his novel The Floating Opera: “The enemy you flee is not exterior to yourself.”

Send A Letter To the Editors