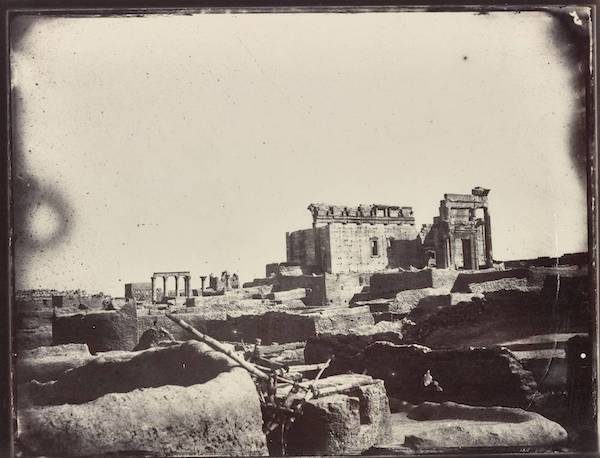

View of the Monumental Arch destroyed by the Islamic State in 2015. Albumen print by Louis Vignes, 1864/Courtesy of the Getty Research Institute.

All places contain history; traces of the past that can be read, contextualized, interpreted, and, with some effort, crafted into knowledge. Some places are so rich in material and textual information that they become archives, deep resources that beseech the senses and necessitate generations of scientific and intellectual exploration.

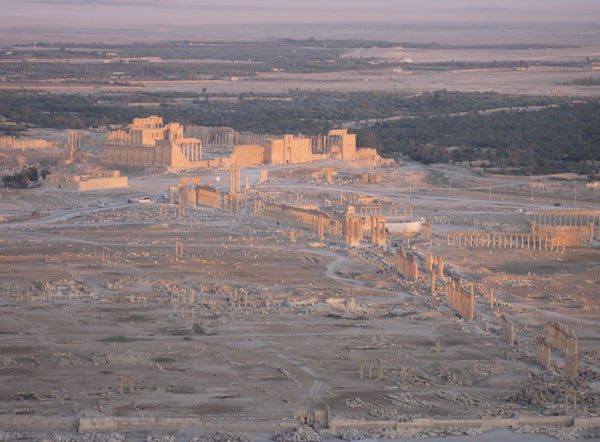

The ancient caravan city of Palmyra, also known as Tadmor in Arabic, is one such place. Stretching three kilometers through the Syrian Desert, its ruins tell enumerable stories, thousands of years in the making. The city was never fully abandoned, and so Palmyra is an archive beyond its buildings: one of people, culture, and conflict across time.

Palmyra prospered in antiquity as Romans and Parthians vied for dominance of the region. In the Byzantine and early Islamic era, Palmyra’s ancient temples were remade into churches and mosques, and, during the early-modern and colonial periods, foreign expeditions documented and secured Palmyrene artifacts for distant museum collections. Syrian and international teams of archaeologists reconstituted the ancient city through excavation and reconstruction in the 20th century.

Detail of two-part panorama featuring the Colonnade Street and the Temple of Bel in Palmyra. Albumen print by Louis Vignes, 1864/Courtesy of the Getty Research Institute.

Each of these phases in history reframed Palmyra, physically changing and conceptually altering the once-thriving metropolis.

And today, militants have caused irrevocable destruction to Palmyra’s monuments and people. Our own, heart-wrenching moment in Palmyra’s history has been met with a variety of responses, including digital reconstruction projects, museum exhibitions, academic conferences, and significant media coverage. Although sometimes uneven and the subject of criticism, these projects signify an impulse to resist the damage done during the current Syrian conflict by reimagining the site as it was before the destruction, or as it may be remade in a more hopeful post-war future.

I have been fortunate enough to have co-curated together with Frances Terpak the online exhibition The Legacy of Ancient Palmyra. This project is the first of its kind taken on by the Getty Research Institute (GRI) in Los Angeles. The focus of the exhibition is the remarkable material held by the GRI, including the earliest known photographs of Palmyra, taken by the French naval officer Louis Vignes in 1864, and a rare set of etchings made after on-site drawings by the French artist and architect Louis François Cassas in 1785.

Together these two collections offer a window into a seemingly distant time in Palmyra’s history, but one that was no less complex than our own. During the 18th and 19th centuries, the ruins of Palmyra and the village of Tadmor contained within its ancient walls were part of the Ottoman Empire. Palmyra was connected to the world through caravans consisting of hundreds of camels, as it had been for thousands of years. Expeditions to the site, like those of Cassas and Vignes, foreshadowed a deeper penetration of Western influence in the region as well as the beginnings of archaeological investigations.

Valley of the Tombs in Palmyra. Etching after Louis-François Cassas, ca. 1799/Courtesy of the Getty Research Institute.

Cassas’ prints were part of a larger survey that documented monuments from Istanbul to Cairo and part of a career that recorded and published views of classical ruins in Rome, Sicily, Greece, and Croatia. Although not known well today, Cassas was recognized by intellectual elites of his day, such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, precisely because he had gone to Palmyra to see and draw these famed ruins.

The work itself, which can be considered the most comprehensive study of Palmyra before the 20th century, consists of close to 100 large-format etchings. These etchings are a collection of technical renderings, architectural plans, landscape views, and reconstructions of the magnificent buildings that have been intentionally demolished in recent years.

The painstaking detail in Cassas’ original drawings and the final prints display his desire to create a body of work that had superb aesthetic value. And by design, his imaginative depictions of the site also became blueprints for European artists to use in works of architecture, painting, sculpture, and the decorative arts.

View of the interior courtyard of the Temple of Bel showing the mudbrick homes in the foreground. Albumen print by Louis Vignes, 1864/Courtesy of the Getty Research Institute.

Neoclassical Europe had already had a taste of Palmyrene art from the earlier and more famous British expedition of Robert Wood and James Dawkins, whose monumental book The Ruins of Palmyra, Otherwise, Tedmor in the Desert (1753) was often cited as a source for architectural inspiration in 18th-century England. For example, the now-destroyed coffered ceiling of the Temple of Bel, which was depicted in the Wood and Dawkins publication, was replicated in the interiors of at least four prominent buildings designed by Robert Adam and others.

Cassas’s goal was to give this audience more material by providing lavish depictions of a style that became to be known as “Roman Baroque.” Although the term is generally not favored by art historians today, “Roman Baroque” suggests what Cassas and his audience found so powerful in Palmyra’s art and architecture. The colossal scale and opulent decorations of the Roman-era buildings in the great cities of the Eastern Mediterranean rivaled some of the best examples of classical architecture found in the West, even in Rome.

Palmyra’s architecture exemplified this concept, and, combined with its location “lost” in the desert, magnified its appeal. Embroiled in the struggles of the French Revolution, thinkers in Cassas’ time readily connected the perceived abandonment and decline of Palmyra as a cautionary tale to the possible destruction of their own civilization.

Imaginary view of Tetrapylon. Etching after Louis-François Cassas, ca. 1799/Courtesy of the Getty Research Institute.

Nearly 80 years after Cassas’ travels to Syria, Louis Vignes brought his camera to Palmyra and moved its ancient monuments into the modern era. To our eyes, Vignes’ images may appear nostalgic, and in light of current events, ghostly, as visages of a past no longer present. But to a 19th-century viewer, they would have been seen as concrete evidence, either validating or refuting the embellishments of earlier accounts. In contrast to the timeless and almost dream-like qualities of Cassas’ images, Vignes grounded Palmyra in a photographic immediacy that places the viewer in the monument.

This 1864 expedition to Palmyra was an offshoot of a larger geological and cultural survey of the Dead Sea region that was sponsored and led by Honoré Théodore Paul Joseph d’Abert, duc de Luynes, a French nobleman with a passion for archaeology, science, biblical history, and technology. Vignes, a ship’s captain hired for the mission because of his knowledge of the regions’ ports, had only briefly trained in photography before embarking on this journey.

The regional survey was meant to be scientific and comprehensive. Along with photographing classical, biblical, and crusader sites, the expedition team documented and mapped the sources of rivers described in the Bible, and collected core samples from the Dead Sea and specimens of its marine life. The expedition brought two small collapsible metal boats across the desert to be reassembled and used for research as needed.

The images produced by Cassas and Vignes are squarely set inside a colonial or orientalist vision of Palmyra, mostly concerned with its classical past. They were made in an interventionist period which deserves unsympathetic criticism for the lasting economic and political effects it caused in the region.

View of Palmyra from Qalaat Shirkuh before the destruction of its major monuments by ISIS. Photo by Judith McKenzie/Manar al-Athar, 2010.

Alongside and inseparable from this fraught history are the beginnings of modern scholarship on Palmyra and around the world. Many scholars from many countries have dedicated their professional careers to researching Palmyra. Through their efforts we know that Palmyra, throughout much of its history, was home to changing multi-ethnic and religiously diverse societies. Modern archaeology has reframed the city in our own time by excavation and decipherment of inscriptions. These images of daily life through the ages, culled together from decades of work by scholars, replace the earlier Western concept of Palmyra as a landscape of romanticized ruins belonging to a lost civilization.

Appallingly, Syrian archaeologists, workers, and others with knowledge of this and other sites in the war-torn country have been targeted and killed in recent years. In some reports, these atrocities have occurred when attempts were made to protect the sites from ISIS looters, who have been systematically seizing and selling antiquities to fund their activities.

Pursuing knowledge about Palmyra cannot undo the damage done. But it can offer new narratives that promote the value and importance of cultural heritage. From a nexus of trade in antiquity to a modern tourist destination, people from diverse backgrounds flocked to Palmyra. Continued engagement with the place, digitally if not physically, will help future generations reframe Palmyra once again.

Send A Letter To the Editors