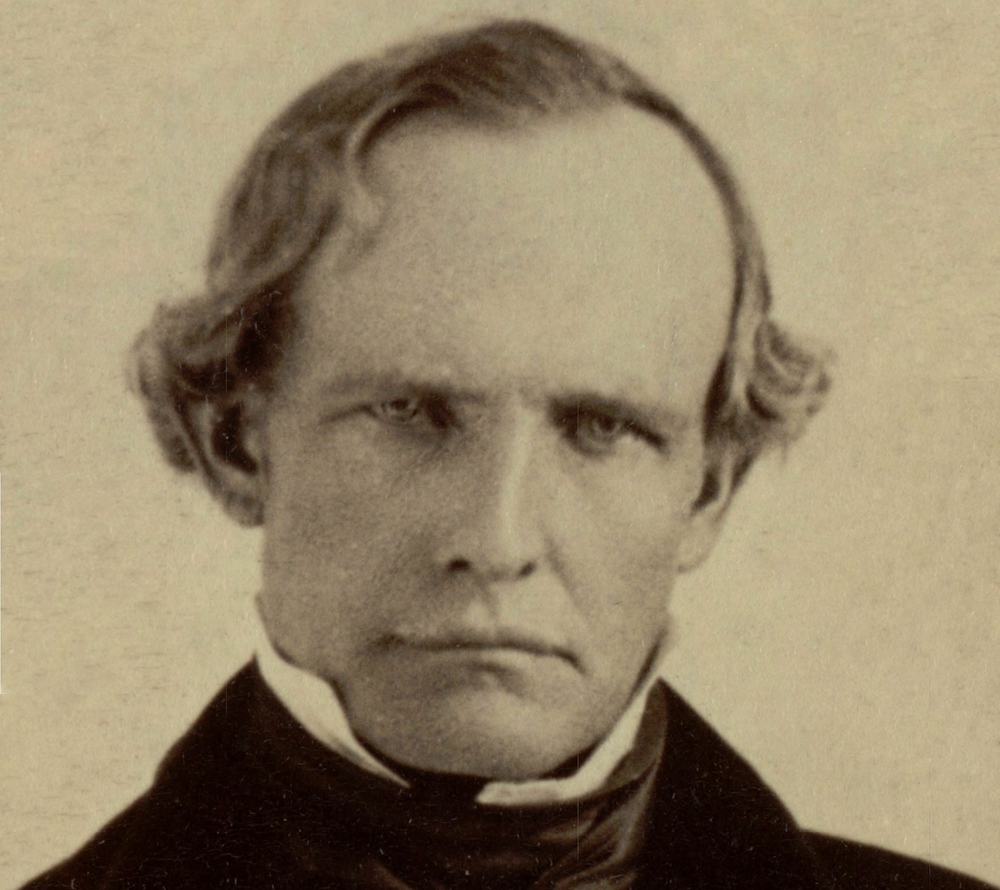

Peter Hardeman Burnett, first governor of California, circa 1860. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Peter Hardeman Burnett had probably the most impressive list of achievements of any leader in the early American West. He served on the supreme court of the Oregon Territory and became the first governor of California.

Peter Hardeman Burnett had probably the most impressive list of achievements of any leader in the early American West. He served on the supreme court of the Oregon Territory and became the first governor of California.

So why has he been forgotten?

Because sometimes history gets things right. Burnett’s stellar resume could not offset his blatant racism and inept leadership, which have denied him a prominent place in the region’s history.

Burnett is best remembered, if he is remembered at all, for his governorship of California, in 1849. He resigned in 1851, with little to show for his time in office, other than failed attempts to win enactment of an exclusion law against African Americans. He made questionable decisions that undermined his leadership, including changing the 1850 Thanksgiving observance from a Thursday to a Saturday, evidently for his own convenience.

Burnett was, for a time, quite popular, overwhelmingly elected governor at the age of 41. But his public career started much earlier, as one of the defense attorneys for Mormon leader Joseph Smith following the so-called Mormon War in Missouri in 1838. A self-taught lawyer, Burnett served three one-year terms as a district attorney for a five-county region in northwest Missouri.

He helped organize and lead the first major wagon train to Oregon, known as the “Great Migration,” in 1843. Once in Oregon, he was elected to the first provisional legislature. He also served as Oregon’s first provisional supreme court judge, was appointed to the Territorial Supreme Court, and opened the first wagon road from Oregon to California, leading about 150 would-be miners to California’s gold fields in 1848.

In California, his new home, he worked with John Sutter Jr. to develop the city of Sacramento; served in the pre-statehood San Francisco Legislative Assembly; was elected a judge on the pre-statehood Superior Tribunal; was elected governor following the 1849 Constitutional Convention; served on the Sacramento city council; and was appointed to the California Supreme Court in 1857.

Burnett was born in Nashville, Tennessee, on November 15, 1807; his mother was a member of the prominent Thomas Hardeman family. But Burnett said his parents struggled to make a living and he grew up poor.

Both sides of his family owned enslaved persons, and—according to the 1840 slave census—Burnett had two of his own in Missouri. Indeed, he may have tried to bring at least one enslaved person to Oregon, as accounts of the 1843 emigration refer to a young African-American woman, or girl, who drowned in the Columbia River, as being attached to the Burnett family.

Even before coming to California, Burnett had issues with race. As a young store owner in Clear Creek, Tennessee, he was responsible for killing an enslaved black man who broke into his store to drink from his whiskey barrel. Burnett set a trap for the burglar by propping a rifle on the counter with a string from the trigger to a window shutter. He went home to sleep and the next morning found the man dead on the floor. Burnett expressed remorse and was not charged with a crime.

In Oregon, Burnett authored an exclusion law against African Americans that provided for a whipping penalty for blacks who refused to leave—up to 39 lashes, whether a man or a woman. The law also allowed slave owners three years to free enslaved persons, in effect legalizing slavery for three years, after an early provisional government had banned slavery entirely. Although the whipping penalty was soon changed, and possibly never executed, it is known in Oregon history as “Peter Burnett’s lash law” and is probably the one thing anyone in Oregon knows about Burnett, if they know anything about him at all.

In California, Burnett joined a heated and divisive debate over race and slavery that extended throughout the states and territories and was tearing the nation apart, culminating in the Civil War. Several delegates to the 1849 Constitutional Convention were slave owners, among them William McKendree Gwin—soon to be chosen as one of California’s first U.S. senators—who owned at least 200 enslaved persons on his Mississippi plantation.

With little debate, the delegates voted to prohibit slavery in the soon-to-be new state, but they deliberated at length as to whether to include a provision in the constitution banning African Americans, before finally deciding that it would be improper to include such a law in the constitution. They did deny blacks the right to vote.

Once elected, Burnett picked up the torch for exclusion in his first annual message to the Legislature. Burnett called exclusion an issue of “the first importance.” He used the same racist arguments he had used in Oregon: African Americans would take jobs from whites, and would be a discontented element in society because they were second-class citizens deprived of the same rights as the white population. To this, he added a prediction that manumitted slaves from the South would be “brought to California in great numbers.” As many as 1,000 blacks, both free and enslaved, were already in California, working in mining camps and at other jobs.

Burnett insisted that banning African Americans would produce the greatest good for the greatest number. “We have certainly the right to prevent any class of population from settling in our state that we may deem injurious to our own society . . . .” He mocked anyone who opposed such a law as succumbing to “weak and sickly sympathy.”

The reaction in California’s leading newspaper, the Daily Alta California in San Francisco, was swift and condemnatory. The newspaper, which had earlier written favorably of Burnett, said an exclusion law would be “a blot unworthy of a people, who had repudiated forever slavery from their shores.”

The Legislature’s response reflected the ongoing divisions over race. The Assembly approved an exclusion measure, but the Senate effectively rejected it, largely through the efforts of abolitionist-leaning Senator David Broderick, who engineered a vote to table it indefinitely. The Legislature did prohibit African Americans from testifying in court against whites.

Burnett was back at it in his 1851 message. He again called for an exclusion law and denounced blacks in even harsher terms than before. “They have no ideas and no recollections of a separate national existence—no alliance with great names of families—no page of history upon which they recorded the glorious deeds of the past—no present privileges—and no hope for the future,” he said.

If Burnett believed this, he didn’t bother to explain what brought these conditions about. He made no mention of Africans being torn from their families and kidnapped from their native lands, no reference to their enslavement and no mention they were denied education and all manner of humane treatment.

He didn’t stop with blacks. He also predicted a war of extermination against the Native American tribes. He would later argue in favor of prohibiting Chinese immigration, writing in his autobiography, Recollections and Opinions of an Old Pioneer, that enterprising and hard-working Chinese would eventually dominate the Western economy “to the ultimate exclusion of the white man.” He said their very presence is “making tyrants and lawless ruffians of our boys” who could not resist the temptation to harass them.

Burnett seems to have had few supporters among lawmakers, and, by his own admission, he shunned advice from others. Had he accepted advice, he might have avoided such reputation-draining decisions as changing Thanksgiving Day, and urging the Legislature to temporarily approve the death penalty for persons convicted of robbery and major property crimes, another proposal for which he was condemned in the press of the day.

Burnett sent his 1851 message to the Legislature on January 7, where lawmakers treated it with disdain. The Assembly declined even to have it read aloud by a clerk. Two days later, on January 9, Burnett abruptly resigned, explaining unconvincingly that he needed to attend to his personal affairs.

The Alta welcomed his resignation with “the most unqualified satisfaction,” saying Burnett had suffered from “an almost unaccountable apathy.’’ It wondered in a later article whether Burnett sought the governor’s chair simply for the “gratification of being known as the first governor of California—the empty honor of a title.”

Burnett’s political career was temporarily revived when Governor J. Neely Johnson appointed him to a vacancy on the California Supreme Court in 1857. But he was again undone by his racism. Burnett wrote the majority opinion in a ruling on January 11, 1859 that would have returned a black man, Archy Lee, to slavery in Mississippi even though he had been brought to California by his owner, and therefore by California law presumably was a free man. Lee’s attorneys maneuvered to have the decision ignored, and Archy Lee was freed. But the decision once again subjected Burnett to unbridled criticism.

After he finished his court term, Burnett retired from public life and became a successful banker in San Francisco. He wrote long treatises on Roman Catholicism, to which he had converted while still in Oregon in 1846.

Burnett’s failures as a public official obscured his significant contributions to California statehood. He argued tirelessly in speeches and in writing for civilian self-government during a period of military rule after Mexico formally yielded California to the United States in 1848, following the Mexican-American War.

In his Recollections, which he finished in 1878, Burnett didn’t defend himself against the criticism of his more questionable decisions. He didn’t mention his final message to the Legislature, or the reasons he resigned as governor, or the Archy Lee case, actions that have relegated him to little more than a footnote in most history books. He died in San Francisco on May 17, 1895.

Send A Letter To the Editors