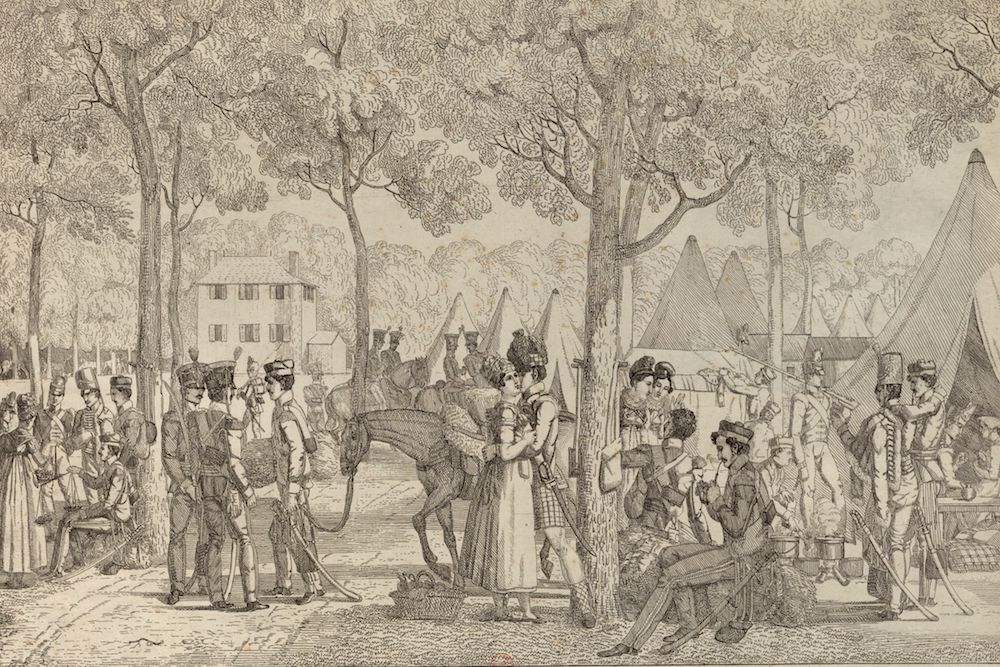

An anonymous engraving, from around 1815, showing English and Scots on the Champs Élysées. Courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

How do you win the peace?

The recent American military occupations in Afghanistan and Iraq highlight the risks of “winning the war, but losing the peace,” to borrow the subtitle of Ali A. Alawi’s book on Iraq. Failed occupations have tremendous costs in money and lives, while exacerbating political instability in occupied nations.

Those seeking to do occupation right often look to the post-World War II occupations of Germany and Japan. But the challenge of making peace after war was most successfully addressed by the first modern peacekeeping occupation, more than 200 years ago, following the defeat of Napoleon in France. This occupation is worth studying because it did not depend on a common external threat—like the Soviet Union in the aftermath of World War II—to make the occupied reliant on the occupiers.

The use of occupation for peacemaking originated in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, which pitted France against most of the other powers of Europe between 1792 and 1815 (with brief breaks in 1802-1803 and 1814-1815). Before this period, victors had routinely conquered territories and demanded “contributions” from the powers they defeated. But during the new “total” wars that followed the French Revolution, victorious countries began to use military occupation as a tool to effect political “liberation,” or regime change, of the defeated nation.

Napoleon’s definitive defeat at the Battle of Waterloo on June 18, 1815, also prompted innovation, leading the Allied powers of Europe eventually to invent a new sort of peacetime occupation, whose aim was to ensure that the defeated French maintain a stable government as well as that the victorious powers receive financial compensation for the costs they had incurred in fighting the former emperor.

This new style of occupation came together slowly. After Waterloo, the British and Prussian armies invaded France, reaching Paris by early July. There, they reinstated the exiled King Louis XVIII, who had ruled for barely a year between the Emperor’s first defeat in March 1814 and his return to power in March 1815. They were soon followed by troops from Austria, Russia, other states in the German Confederation, Denmark, and even Piedmont-Sardinia. By mid-July, some 1.2 million troops covered two-thirds of the territory of France, often engaging in pillaging and violence against local inhabitants. Although many of these troops were happy to live off the defeated French indefinitely, their leaders faced the challenge of how to transition from war to peace in France.

This question generated considerable disagreement among Allied leaders. Some members of the coalition, particularly Prussia and Austria but also British prime minister Lord Liverpool, thought France needed to be punished for having backed Napoleon in his return to power. They wanted to exact heavy financial indemnities—as much as 1.2 billion francs—as well as significant territorial concessions, particularly in Alsace and Lorraine, which were to be transferred to Prussia and Austria.

But such a punitive approach was resisted by other Allied leaders, including the Russian Tsar Alexander and, especially, the British foreign minister, Lord Castlereagh, and the British commander, the Duke of Wellington, who maintained that it would destabilize France. According to these more moderate Allied leaders, the main goal of any settlement was to ensure durable peace—as well as financial reparations—for the nations of Europe.

Wellington proposed a temporary occupation of the defeated country until the Allies had been financially compensated, arguing in a letter to Castlereagh dated August 11, 1815: “These measures will not only give us, during the period of occupation, all the military security which could be expected from the permanent cession, but, if carried into execution in the spirit in which they are conceived, they are in themselves the bond of peace.”

Following several months of negotiations between the Allied diplomats and French foreign ministers, this more moderate approach was instituted in the Second Treaty of Paris, signed on November 20, 1815. This treaty’s main goals were to ensure “proper indemnities for the past and solid guarantees for the future.” France was placed under the oversight of the Allies until they were satisfied it was no longer a threat to Europe. In addition to a temporary occupation at French expense, the treaty required the payment of a still substantial war indemnity. Maintaining a Council of Allied Ambassadors to monitor political developments in Paris, the treaty also formalized a Quadruple Alliance (of Britain, Russia, Prussia, and Austria) to protect “order” against revolution, thereby promoting international political cooperation in Europe. Unprecedented in the law of war, this settlement marked a new approach to peacekeeping.

In this settlement, the key to guaranteeing security in France was the occupation force. The multinational peacekeeping force, placed under the integrated command of the Duke of Wellington, was the first of its kind. Stationed in and around 18 garrisons in seven departments along the northeastern frontier, the occupation army totaled 150,000 men: 30,000 from each of the four main powers—Britain, Russia, Prussia, and Austria—plus another 30,000 from minor German and Danish powers. The French would pay for this force for up to five years, until the French had fulfilled their financial obligations to the Allies.

These financial requirements were substantial. In addition to paying the provisions, salaries, and equipment for 150,000 men and 50,000 horses and reimbursing the yet-to-be-determined claims of Allied subjects from the revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, the French were required to pay a war indemnity, ultimately set at 700 million francs. Payment of this compensation was a precondition for the end of the occupation. Although the indemnity had antecedents in the sums demanded by France from Prussia, Austria, and other countries during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, it was designed as a “reparation,” in the modern sense of repairing damage to rejoin the community of nations.

To ensure the financial and political stability of the defeated nation, the post-Napoleonic settlement also instituted the Council of Allied Ambassadors. Composed of the ambassadors to France of the four major powers allied against Napoleon (Russia, Prussia, Austria, and the U.K.), plus the commander of the occupying army when he was in Paris, this council met in the French capital at least twice per week throughout the occupation to monitor the new government. Aiming not just to contain civil war but also to remake the political culture in France, the council sought to forge a middle path between Jacobin revolutionaries on the one hand and extreme conservatives on the other.

This “occupation of guarantee,” as it was called, constituted a considerable burden on the French, especially in the northeast, where most of the troops were stationed—sometimes in the homes of local inhabitants. In addition to financing requisitions and reparations through taxes and bonds, they were subject to random “contributions” in money and kind. They also endured considerable violence, including fights, brawls, murders, and rapes. In response, Allied and French authorities worked to minimize violence and promote “good harmony” between occupying soldiers and local inhabitants through cooperative regulation of their subjects and soldiers and adjudication of any offenses. These efforts promoted considerable accommodation and even fraternization between occupiers and occupied.

Under pressure from the occupying army and the Allied Council, the restored monarchy moved quickly to rebuild the government and treasury in France. In September 1816, the council pushed the king to dissolve the ultraroyalist Chamber of Deputies. In the elections that followed, conservatives lost seats to moderates. This move paved the way for a number of important liberal reforms regarding elections, military recruitment, the press, and the budget, which was especially important for financing the payments due to the Allies. By early 1818, the French government convinced the Allied leadership that it was stable and solvent enough to end the occupation two years ahead of schedule. At a congress at Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen) in Prussian territory, following negotiation over the final payments of the reparations required by the Second Treaty of Paris, the Allies agreed to evacuate France by the end of November.

In the end, the “occupation of guarantee” was one of the most successful peacemaking operations ever. The Allied forces in France did not make much of an effort to win “the hearts and minds” of the local inhabitants, as recent occupiers have endeavored with mixed success. Nonetheless, they promoted the political and economic reconstruction of the defeated power.

This occupation was successful for many reasons. It was genuinely multilateral in composition. In addition, even though the occupying troops came from many nations, their leaders could almost all communicate in the language of the occupied. The architects of the occupation established clear goals for it, from the beginning. Unlike the initial military occupation of the summer of 1815, the “occupation of guarantee” guaranteed the sovereignty of the new government. The occupying powers made effective use of existing institutions, and they enlisted cooperation from local authorities to mediate between occupying forces and occupied communities. The occupation also had effective leadership, in the Russian commander Count Mikhail Semenovich Vorontsov, the Austrian commander (a former French nobleman) Baron Johann Maria Philipp de Frimont, and especially in the occupation’s commander-in-chief, the Duke of Wellington (who had learned from his previous experiences in India and Spain).

Unfortunately, the lessons of this first modern peacekeeping mission have often been ignored by subsequent occupiers, at great expense. The lack of historical memory and preparation is all too apparent in Afghanistan and Iraq, where lives continue to be lost among both allied forces and civilian populations, more than a decade after invasions.

From the beginning, these more recent occupations lacked clear goals. Rather than using reparations as incentives for the occupied to build stable governments, the American occupiers expended billions of their own dollars, mostly on self-defense rather than on economic development. Americans, often lacking essential linguistic and cultural knowledge to communicate with the occupied, failed to obtain the cooperation of local authorities, who themselves had little political experience. In many localities, there were no civilian institutions on which the occupiers could rely.

Moreover, the cultural—and especially religious—differences between occupiers and occupied fueled mistrust on both sides. Unlike the French in 1815, the inhabitants of Afghanistan and Iraq were not necessarily motivated to rejoin the community of nations. Sadly, these challenges to a successful occupation were ignored by our political leaders.

Perhaps the story of post-Napoleonic France, if it were better known, could warn against similar efforts at regime change in the future.

Send A Letter To the Editors