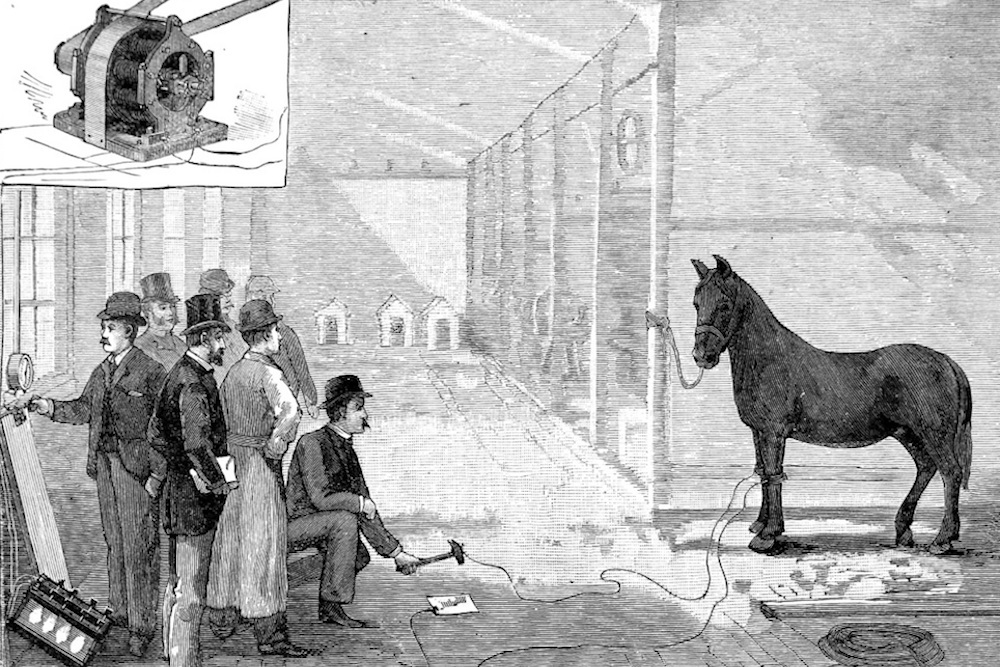

An illustration of Harold Brown electrocuting a horse with alternating current power in December 1888 at Thomas Edison’s West Orange laboratory, from Scientific American. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Before new forms of technology became a regular fact of American life, the mingling of public hopes and fears around these innovations was more obvious than it is today. By the 1880s, for example, people had become accustomed to gas-powered light, but electric lighting was still a novelty. Famed American inventor Thomas Edison built up his system for the distribution of electric power, but in 1886 he gained a formidable rival who threatened to bring his whole company down. George Westinghouse’s innovative and effective “alternating” or “pulsating” current, AC, was far cheaper and more efficient than the Edison Electric Light Company’s “direct” current, DC. Edison lobbied politicians and the press to discredit AC, and by extension, Westinghouse. In 1888 and 1889, Edison, along with his representatives and allies in New York, began to use spectacle to label AC a killer.

The war that erupted between Edison and Westinghouse would go down in history as the “battle of the currents.” It’s the story behind two of America’s industrial giants (General Electric and Westinghouse) and the choice that defined America’s future: electricity traveling across vast networks of cables and wires and poles, powering a nation. Integrating technology into our lives is now so routine that it’s difficult to imagine the high emotional pitch of the battle of the currents—or just how it came to involve electrocuting animals in public.

On July 30, 1888, in a lecture hall at Columbia College in New York City, electrician Howard P. Brown escorted a large black dog onto the stage in front of 700 electricians, government officials, and policymakers. After a short lecture explaining the difference between Edison’s direct current and Westinghouse’s alternating electrical current, Brown and his assistants fastened electrodes to the dog’s fore and hind legs.

Brown administered a range of intensities of DC. The first jolt caused the dog to leap into the air. The second jolt caused the dog to struggle. After a third shock, the dog ripped off his muzzle. Brown continued increasing the volts up to 1000, when the dog collapsed, breathing heavily. Brown then attached the wires to a generator, distributing Westinghouse-style AC current. At 330 volts, the charge immediately killed the creature, drawing gasps from the crowd.

“The duration of the current was only five seconds,” wrote a reporter for The Sun the next day, “but when it was cut off the troubles of the big black dog were over.”

Despite seeing the animal writhing in pain, Brown asserted that death by electricity was humane and painless. As he went to bring out a second animal, a representative from the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals ended the demonstration, handing him a $250 fine.

How did this torture of animals in the name of science and public safety come about? In the midst of the battle over adopting AC or DC, the New York State Legislature was also considering electricity as a new method for capital punishment. Brown, who had been secretly encouraged by Thomas Edison, held his series of public demonstrations to prove that alternating current could be lethal, and thus was ideal for use in executions. The effects of these gruesome performances on policymakers and the early public understanding of electricity reveal how new technology gets adopted and the many ways its reception can be manipulated—and influenced by freak accidents.

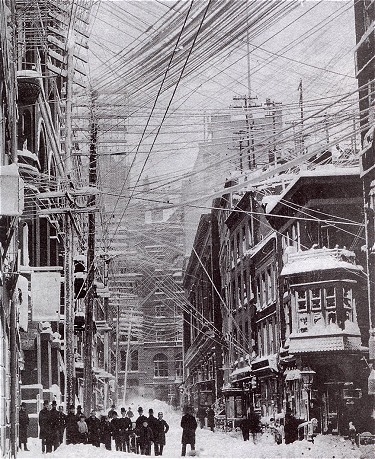

Photograph of a tangle of telephone, telegraph, and power lines over the streets of New York City after the Great Blizzard of 1888. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/The New York Historical Society.

The rivalry between Edison and Westinghouse had been brewing for years, but it came to a head a few months earlier in March 1888, when two feet of snow fell on New York and thick ice pulled telephone poles down. Telegraph and electric wires lay so tangled in places that poles needed to be sawed in half. After the deaths of line workers and even children, it became apparent that the canopy of overhead wires that had grown up over the past few years could be lethal.

With the blizzard, the battle of the currents came into public view. Before Westinghouse arrived in New York, there hadn’t been a problem with snow on the wires because Edison’s company buried its cables underground. Westinghouse, though, couldn’t get permits to dig because of Edison’s close ties with government officials. So Westinghouse was forced to hang wires overhead.

Telegraph, telephone, and electric companies shared the poles, but the political message became one of public safety, that alternating, high-voltage current was running through those wires. It was common knowledge that the blue-collar maintenance men who climbed poles to maintain the city’s vast network of wires had a dangerous job. But with live wires dangling free, their accidental deaths came to be seen as those of martyrs.

Anxiety about overhead wires coalesced in July with the publication of an impassioned letter to the editor of the New York Evening Post. Electrician Howard Brown took a stand against alternating current. Brown eulogized the “scores killed and maimed by the ‘pulsating’ current.” Brown’s letter called for political action and reform to make the city safe again.

Brown pointed his finger at the “damnable,” “alternating current” used by the arc lighting systems of Westinghouse’s company. “Among electric lighting men it is appropriately called ‘undertaker’s wire,’” he explained, “and the frequent fatalities it causes justify the name.” He went so far as to say that Westinghouse’s company provided electricity at a cheaper cost not because AC had superior efficiency but because they were cutting corners.

In case words weren’t enough to rally the public, Brown intended to put on a show. His public health campaign sought a neologism for death by electricity. Magazines advertised contests to coin this new word. Suggestions included various connections between electricity, death, and the body. The Sacramento Union provided a long list, from “electromort” and “electricide” to “joltacuss.” The term “electrocution” eventually won out, effectively making alternating current synonymous with death.

The discussion of death by electricity and its adoption as the method of capital punishment in New York state went hand in hand with Harold Brown’s electrocution demonstrations. Under the guise of determining an effective and humane standard for New York state’s proposed legislation, Brown continued to denounce Westinghouse’s alternating current as the best way to kill living creatures.

Early in the summer of 1888, Brown received an invitation to Edison’s new laboratory in West Orange, New Jersey. Edison encouraged Brown to take his advocacy campaign public in the form of demonstrations. They would prove, scientifically, that alternating current was lethal and direct current was not. And to do this, they would use a visceral and unforgettable display: electrocuting animals.

Four days after Brown’s Columbia demonstration was prematurely cut short, he returned to conduct a follow-up demonstration using three dogs. Public outrage erupted, and observers questioned the scientific legitimacy of Brown’s claims. In the ensuing debate, electricians claimed that the initial low-voltage DC shocks weakened the dogs, making the final high-voltage shock seem more lethal than it would have been in isolation.

On the eve of the adoption of electrocution for capital punishment in New York, with the standard still not set, Brown partnered with Edison at the latter’s West Orange laboratory. In December 1888, two calves and a horse were electrocuted, in order to better test the weight of the animal against the average size of a human subject. The electrocution of a 1,230-pound horse was particularly elaborate.

Westinghouse finally spoke out. In a letter to the editor of the New York Sun, Westinghouse debunked Brown‘s claims. Five days later, Brown responded with another letter to the editor, this time in The New York Times. Brown denied his affiliation with Edison, or at least any ties involving compensation. Brown challenged Westinghouse to a duel using the currents and offered to see who would survive. The duel never took place.

Westinghouse finally won back some credit in August 1889, when a burglary at Brown’s New York offices led to a massive exposé of Edison funding his efforts. But Westinghouse’s triumph didn’t last long.

The war of the currents came to a head in October 1889. Just after noon on a Friday, high up on the poles at the corner of Chambers and Center streets in lower Manhattan, Western Union line worker John Feeks stripped a tangled mess of dead wires. Feeks shivered, then bolted upright, paralyzed. A second later, he tumbled from his perch and was caught in the canopy of telegraph wires. The loose, live wires sent electricity pulsing through his body. Forty feet above the busy street, Feeks caught fire. It took an hour for emergency responders to arrive, extinguish the fire, and extricate his charred body.

Feeks’ death stood as a turning point in the battle of the currents for several reasons. It occurred in the harsh light of day before thousands of people. The story circulated both as a word-of-mouth tale that fed the rumor mill and a high-profile front-page newspaper story. Newspapers made an event out of Feeks’ death, covering his autopsy, funeral, and widow’s bereavement.

Like Brown’s campaign against AC, Feeks’ death stirred the city to the core. There was nothing rational or pragmatic about the subsequent crusade by New York mayor Hugh J. Grant to indict the electrical companies to suspend business. Feeks became a poster boy for the public to rally against AC, spurring Grant to convene committees and courts to push for legislation to clean up the overhead wires once and for all.

Yet the truly fateful decisions got made out of public view. In 1892, facing pressure to economize and upgrade, Edison’s two biggest investors—J.P. Morgan and Cornelius Vanderbilt—made the executive decision to switch to AC. The subsequent merger between the Edison Electric Lighting Company and Thompson-Houston electric formed the Edison General Electric Company (later General Electric).

In 1893, Westinghouse won the contract to supply electric to the much-anticipated Columbian Exposition in Chicago. That World’s Fair unveiled the Ferris wheel and the first motion picture machines and also solidified a promising future for cheap, safe, and efficient alternating current as the standard in America.

The battle of the currents was never really about determining which system was best. It was, instead, a rivalry between two industry giants, with helpless animals and line workers as collateral damage. In a sense, Edison’s strategy succeeded in popularizing the notion that electricity was dangerous, which was cemented with the execution of William Kemmler in an electric chair in 1890. But Westinghouse also “won” through his unflinching embrace of a more effective technology, which eventually became the industry standard. Exploiting ignorance and using fear to manipulate the public can have significant effects on perceptions, but isn’t always enough to influence adoption when it comes to new technologies.

Send A Letter To the Editors