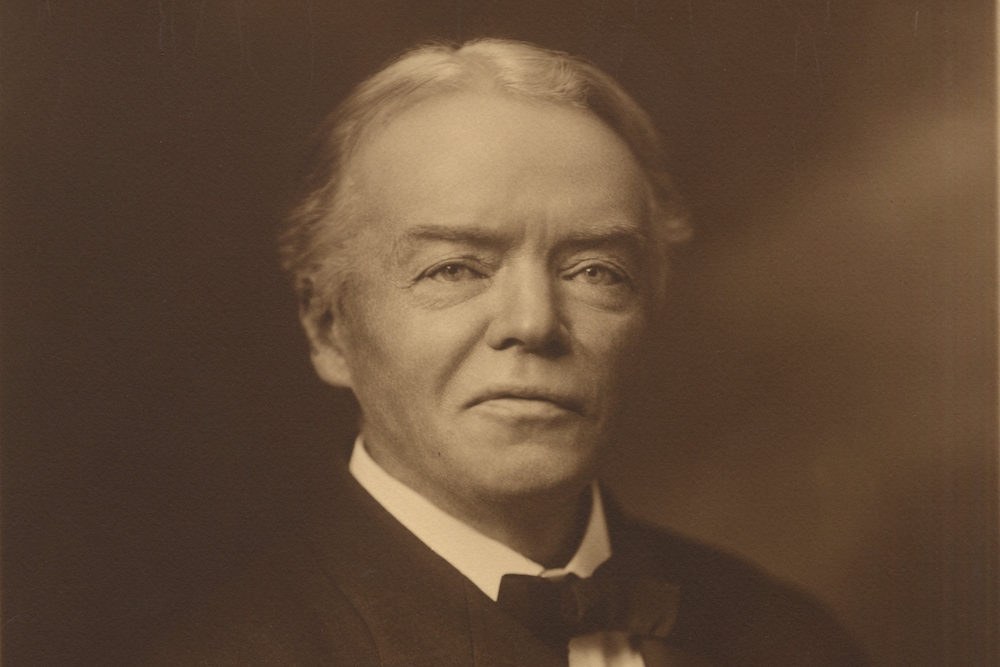

A portrait of Josiah Royce. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

If you’re a Californian who doesn’t know the name Josiah Royce, shame on you. And shame on the schools, libraries, and intellectuals who have allowed us to forget the greatest thinker the Golden State ever produced.

When he is remembered, Royce—born in 1855 in a Grass Valley mining camp, raised in San Francisco, and educated at UC Berkeley where he was one of the first graduates—is often described as a once-famous philosopher. But that doesn’t do justice to a man whose groundbreaking work ranged over ideas as big and wide as his home state itself.

Moreover, his writing—if we would only read it—offers astonishingly fresh wisdom for Californians facing problems from discrimination to housing to the power of Facebook.

Royce was the sort of scholar who learned Sanskrit so he could study early Buddhist texts. He wrote important books and papers on the scientific method, religion, psychology (even serving as president of the American Psychological Association), insurance, race relations, and social ethics. He published literary criticism, came up with concepts of global peace that inspired the League of Nations, and identified important foundations of logic, mathematics, and cybernetics.

Perhaps most significant to Californians, he authored a history of California that was ahead of its time in focusing on the role of women, and demonstrating how the state was built on the exploitation of non-whites. California’s story also deeply informed his most important philosophical work—on how communities, and our loyalty to communities—shapes individuals.

“My earliest recollections include a very frequent wonder as to what my elders meant when they said this was a new community,” he would recall of Grass Valley, where he lived during his early childhood, watching it develop from a camp into a town, with a local government, schools, taverns, churches, and newspapers.

“I strongly feel that my deepest motives and problems have centered around the Idea of the Community, although this idea has only come gradually to my clear consciousness,” he wrote as a professor at Harvard University, where his colleagues included William James and George Santayana, and his students included T.S. Eliot and W.E.B. Du Bois. “This was what I was intensely feeling, in the days when my sisters and I looked across the Sacramento Valley and wondered about the great world beyond our mountains.”

In 21st century California, Royce’s intense focus on local community feels very new again—speaking deeply to our obsessions with health, inequality, equity, and politics in the places where we live.

Royce’s 1886 history, California: A Study Of American Character, described Californians as careless, hasty, and blind to their social duties, but also “cheerful, energetic, courageous and teachable.”

We were too individualistic, he argued, and failed to understand the ways in which communities shape us. “Individuals without community are without substance, while communities without individuals are blind,” he wrote.

And he was deeply critical of how the Americans settling California discriminated against foreign immigrants, warning: “You cannot build up a prosperous and peaceful community so long as you pass laws to oppress and torment a large resident class of the community.”

But Royce was most distressed by the American Californians’ treatment of the Californios and the Native Americans (including, in his account, everything from land theft to lynchings), thus producing a “disaster to them” and a “disgrace and degradation to ourselves.” This criticism of the American conquest of California—“one of the least credible affairs in the highly discreditable Mexican War”—cost him friendships. But he published his book anyway, as a warning against America’s imperialist tendencies.

Around the time when American historians were discussing Manifest Destiny and the closing of the frontier, Royce was having none of it. “The American as conqueror … wants to persuade not only the world but himself that he is doing God service in a peaceable spirit, even when he violently takes what he has determined to get,” Royce wrote, adding his hope that “when our nation is another time about to serve the devil, it will do so with more frankness, and will deceive itself less by half-conscious cant.”

When California did advance, he wrote, it was because people worked together to build genuine communities. His philosophy was one of “loyalty” to community first—“My life means nothing, either theoretically or practically, unless I am a member of a community,” he wrote. He also said: “I never felt a feeling that I knew or could know to be unlike the feelings of other people. I never consciously thought, except after patterns that the world or my fellows set for me.”

And he criticized the heroic individualism he saw championed by the likes of Walt Whitman and Ralph Waldo Emerson, and ultimately developed a metaphysics that conceived of reality as infinite community of minds. Such a community may sound something like Facebook, but Royce warned specifically against exploiting social connections to pursue great fortunes.

“We are all but dust, save as this social order gives us life. When we think it our instrument, our plaything, and make our private fortunes the one object, then this social order rapidly becomes vile to us; we call it sordid, degraded, corrupt, unspiritual, and ask how we may escape from it forever,” he wrote. “But if we turn again and serve the social order, and not merely ourselves, we soon find that what we are serving is simply our own highest spiritual destiny in bodily form.”

Royce died in 1916, but he is not totally dead. UCLA’s Royce Hall is named for him. There is an international society of Royce scholars, and Grass Valley has hosted a play in his honor. Cal State Bakersfield philosophy professor Jacquelyn Ann K. Kegley still teaches Royce in her contemporary philosophy course, and says, “when students read him, they become very intrigued about his communal approach.”

And Royce’s early judgments of California and its people still influence the skeptical way in which we see each other—and the sense that we might better address our problems if we could somehow come together.

“A general sense of social irresponsibility is, even today, the average Californian’s easiest failing,” he wrote in 1886. “In short, the Californian has too often come to love mere fullness of life and lack reverence for the relations of life.”

Send A Letter To the Editors