Portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven when composing Missa Solemnis, painted by Joseph Karl Stieler 1820. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Ludwig van Beethoven occupies a larger-than-life place in our imaginations, all the more so because late in his life he accomplished the seemingly impossible: He continued to compose beautiful and enduring music even as he went deaf.

This achievement is often seen as an example of super-heroic determination, a triumph of the human spirit that tests the boundaries of our species’ ingenuity. But Beethoven the man was not the Beethoven of our imaginations. His story, for all its wonder, is no myth; it offers unfussy but lasting lessons about music, hearing, and disability.

To begin with, accounts of Beethoven’s triumph are often overdone. He did not completely lose his hearing until the last decade of his life, if even then. For most of his adulthood he experienced progressive hearing loss, as many of us do as we age. When he wrote the Fifth Symphony, his most recognizable work, he could hear well enough to correct mistakes in the performance.

And Beethoven wasn’t a “supercrip,” the term for a person who responds to a disability in ways that inspire others but also set unreasonable expectations. He never claimed to be overcoming his hearing loss. Indeed, he accepted it and adapted to it, and this left recognizable marks on his music.

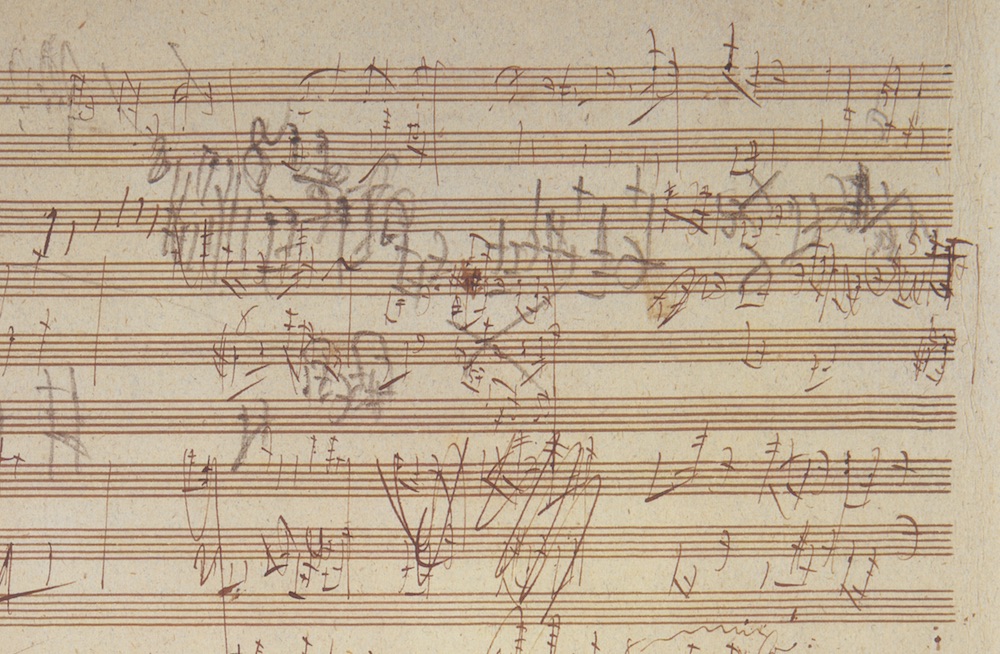

Beethoven’s manuscript of the piano sonata in E Major, Op. 109, shows him creating music on paper, getting carried away with rhythmic, repetitive writing patterns that mirror the emphatic rhythms of much of his music. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Where can those marks be found? The most obvious answers to that question are probably wrong, or at least misleading. Beethoven wrote a lot of loud music, but for someone with hearing loss, loud music is not necessarily better. Indeed, loud music can be painful to failing ears. Listening to a quiet piano sonata in an environment without distractions would likely be more pleasant than hearing a dramatic symphony.

Instead, look for his use of repeating phrases. Repetition is particularly important to someone who is unable to absorb everything on first hearing. Beethoven’s music abounds in repetition, especially repetition of short, highly recognizable units. Musicians call them motives. Beethoven established motives as the building blocks of his longer pieces, a process imitated by many later composers.

This is why the four-note motive at the beginning of the Fifth Symphony is repeated throughout the work. When he wrote this music, Beethoven needed to augment his perception of aural cues, much as a person with progressive hearing loss might augment their understanding of speech by beginning to read lips even if they’re not conscious they’re doing so.

Another sign can be found in his pianos, which changed over Beethoven’s lifetime. The early Viennese pianos he played as a young man had a clear, bell-like sound that was evidently easy for him to hear even as his hearing faded. As he grew older, he became more, not less, attached to his pianos, but what he needed from them was different.

The English Broadwood piano he owned during the last decade of his life was both louder and muddier sounding than the ones with which he grew up—again, the exact opposite of what someone with hearing loss would seem to require.

But Beethoven fell in love with the Broadwood for another reason entirely. It was vibrationally alive. The soundboard, which amplifies the vibrations produced by the strings, was connected directly to the body of the instrument, conveying those vibrations back to the keys and even to the floor beneath the instrument. Thus, though he was increasingly deaf, Beethoven began to feel sound in an entirely new way.

Late in his life, Beethoven commissioned the creation of a specially designed resonator that would be placed over his piano to magnify both sound and vibration. Recently researchers recreated the resonator; the results can be heard on a new recording of his last three sonatas made by fortepianist Tom Beghin. The preparations for Beghin’s recording made it clear just how important touch had become in Beethoven’s experience of music in his last years. The piano music he wrote at this time incorporated powerful repeated chords, new ways of resolving harmonies, and carefully synchronized passages in which the two hands combine to set the frame of the instrument vibrating from top to bottom.

Beethoven also used his eyes to create music. It has been said that both Mozart and Beethoven would compose an entire piece of music in their heads before writing it down. Scholars have known for decades that neither composer ever claimed to have done anything of the sort, but the story persists—perhaps because it provides an idea that is easy to grasp. If this story were true, it would demystify how Beethoven composed in his late years after his ears had failed him.

But Beethoven’s creative process was actually less daunting than the myth would have us believe. When you look at virtually any Beethoven manuscript or sketch, you can see that he was creating music on paper, frequently crossing out and replacing things that didn’t look right, or getting carried away with rhythmic, repetitive writing patterns that mirror the emphatic rhythms of much of his music. He heard what he saw and felt as his pen crossed the paper again and again in arcs and arabesques of musical creativity.

His final string quartets—actual products of his deafness—have a reputation for a kind of profundity that few nonmusicians could describe in words. There is no easy triumph or memorable musical tidbit to be found in them, but they contain a novel sonic universe that seems all the more remarkable when we know that they were written by a man who could not hear. Beethoven created these new textures and sonorities because he was being led by his eyes as much as by his memories of sound. Rather than detracting from his creative process, his deafness added dimensions to these late works that would not have been there otherwise.

Today, Beethoven says less to us about genius and more about how to come to terms with a disability. His experience resonates in an era where forms of human difference have been given unprecedented respect, and words like neurodiversity have entered our vocabulary. Neurodiversity—the idea that all humans occupy a spectrum that includes conditions once considered to be tragic illnesses—has helped bring autism, bipolarity, and depression out of the shadows. In this context it is easier to understand Beethoven’s hearing problems as a normal part of human experience.

Music is a multifaceted medium that inspires people to move, to feel, to watch, to think, and to share experiences with others. If composition were a magical superpower, the music of the great composers would not speak to the rest of us. The story Beethoven tells us is not one of triumphing over adversity, but one of acceptance of what cannot be changed, and of creative adaptation employing the tools at hand. It’s time we welcomed Beethoven on his own terms.

Send A Letter To the Editors