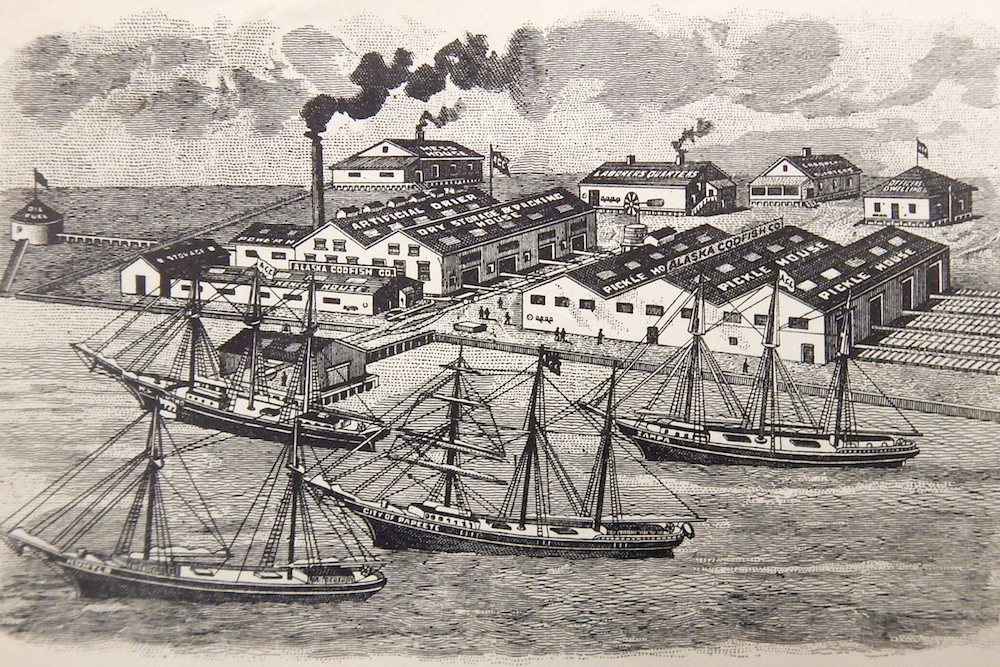

The Alaska Codfish Company in San Francisco, California boasted being “successful curers of hard dried, boneless and whole codfish for export.” Courtesy of the Freshwater and Marine Image Bank at the University of Washington.

An affliction jocularly known as “codfish fever” swept San Francisco in the late 1800s. Caught up in the craze, a number of enterprising young men set to sea in whatever sort of vessels they could manage and headed to Alaska. They were going to catch codfish to salt and sell. Later, the industry journal Pacific Fisherman characterized the phenomenon as one of “dauntless enterprise and arduous endeavor, marked by many periods of discouragement.”

Codfish fever got its start in the years following the discovery of gold in central California in 1848, when San Francisco grew quickly from a sleepy hamlet into a thriving commercial center. Many of those who migrated to California during the Gold Rush were from western Europe. For them, salted cod was a dietary staple.

With their big, sad eyes and lack of distinguishing features, cod have a somewhat homely appearance. Pacific cod reach maturity at an age of 4 or 5 years, at which time the fish ranges in length from about 20 to 23 inches. Older, exceptional specimens can be 6 feet long and weigh up to about 85 pounds.

Nutritionally, cod flesh is high in protein and very low in fat. In addition to being simple to produce (salted cod is simply cod that has been preserved by salting and drying), the food has a long shelf life and is easily transportable. Prior to cooking, the fish is freshened—rehydrated and desalted—by soaking it in cold, fresh water. When cooked, the flesh of cod is white, flakes well and has a mild, slightly sweet flavor that lends itself to a variety of preparations.

Initially, East Coast merchants supplied Californians with salted Atlantic cod shipped via the Isthmus of Panama or Cape Horn. But this was a long, expensive journey for the fish, and California entrepreneurs recognized an opportunity to replace Atlantic cod with Pacific cod.

It was one Captain Mathew Turner, an opportunistic merchant, who pioneered the U.S. Pacific cod fishery.

In 1857, Turner sailed the 120-ton brig Timandra from San Francisco, carrying cargo for the Russian port of Nicolaevsk. It was early in the season, and ice on the river where the port was located kept Turner waiting for three weeks in the Okhotsk Sea. During the wait, the Timandra’s crew, as a pastime, began fishing with handlines over the side of the ship. The men were surprised at the abundance of codfish they encountered. Turner himself had never previously seen codfish—the Pacific variety is virtually identical to its Atlantic cousin—but he was aware of their market value.

In 1863, Turner made another trading voyage to Russia. This time, he provisioned the Timandra with fishing gear and 25 tons of salt, planning to catch codfish on the return voyage. The trip was a success; the Timandra returned to San Francisco laden with 30 tons of salted cod—the first-ever cargo of salted cod from the Pacific fishing grounds to be landed on the U.S. West Coast. The fish were air dried on Yerba Buena Island, in San Francisco, then sold locally for 14 cents per pound—about $4 per pound in today’s dollars.

Captain Turner’s success inspired others, and in 1865, six small schooners that had been built for New England fisheries sailed around Cape Horn and then set off from San Francisco to the Okhotsk Sea fishing grounds.

Turner himself chose to prospect nearer home. In late March, he sailed for Alaska on the 45-ton schooner Porpoise and about a month later arrived at the Shumagin Islands, which are along the southern shore of the Alaska Peninsula. The fishing was good, but Turner feared the market would be glutted when the Okhotsk Sea fleet returned, so he departed for San Francisco before filling his vessel to capacity. The Porpoise arrived home in early July—well before the Okhotsk Sea fleet—with 30 tons of salted cod. It was the first-ever delivery of codfish from Alaska.

The prospects of the codfish industry sparked a lot of interest, and it seemed for a while that anyone in San Francisco who could get their hands on a boat—even a marginally suitable boat—entered the cod-fishing trade. Among them was a junk-and-secondhand-goods dealer who started in the business with the brig Glencoe: “Like everything else that old John had, the vessel was poor, the salt was poor, and the fish were, of course, yellow or sour, dried up or slimy, but they went onto the market and helped damn Pacific codfish,” explained C. P. Overton, of San Francisco’s Union Fish Company, in 1906.

Another colorful character was Nick Bichard, who was born in Great Britain but amassed a fortune in the Civil War and dispatched a motley array of ships to catch cod. In Overton’s words, Bichard was a “large, swarthy man, erratic in speech and action, mixing codfish, coal, lumber, and junk, keeping most of his books in his head, he never knew what his cargoes cost him or what they sold for.” Eventually, the vagaries of the codfish industry absorbed all his money, ships, and considerable properties, and he died almost penniless.

Codfish fever was in full swing. The next spring, March 1866, 18 vessels, each carrying from three to six dories and a crew of 10 to 18 men, departed San Francisco for the northern fishing grounds. In all, the vessels caught 706,200 cod, with a salted weight of 1,614 tons. Notably, a portion of the catch—255 tons—was caught in Alaska, on grounds discovered by vessels en route to the Okhotsk Sea, and the best catches came from the vicinity of the Shumagin Islands, which quickly became the center of the industry as fewer and fewer of the San Francisco fishermen bothered traveling to the Okhotsk Sea.

Unfortunately, few of the new entrants into the business knew anything about catching or, very importantly, properly curing the fish. Later, C. P. Overton described the early years of his city’s codfish industry in less-than-flattering terms:

[The Californians] were a rough and ready people and when they went into the codfish business they went in on the same plan. Any old vessel would do, any kind of salt would do, any sort of tanks or butts [barrels] in any sort of shed would do. The fish were carelessly cured with stained and dirty salt; they were kept in leaky butts or were even piled up on the floor in dry salt, exposed to the air and not in pickle [brine] at all … Under such conditions the finest kind of codfish are necessarily turned out yellow, hard, sour, tough, everything that is bad and such undesirable goods naturally are salable only to camps and among the poorest and least fastidious consumers.

Within just a few years, however, the trade began to be professionalized. The earliest fish merchants were, according to Overton, “two enterprising Yankees of the old school” who had gained their first experience in the codfish trade by selling salted cod on commission, and who would do “anything else that promised a dollar.” They bought salted fish, dried them, and sold cod liver oil and other products.

Cod fishermen with cod on Gus Sojberg’s dock in Unga, Alaska. Courtesy of Peggy Arness.

In 1867, the year the U.S. purchased Alaska from Russia, the first permanent business on the West Coast devoted exclusively to the fish trade opened. San Francisco businessman Thomas W. McCollam saw an opportunity in conducting a codfish business “on the most approved methods” and bought his first cargo of salted cod. The following year, McCollam journeyed to New England, where he purchased the fishing schooners Wild Gazelle, Flying Mist, and Rippling Wave. The three vessels departed for San Francisco, but the Rippling Wave was lost while transiting the Strait of Magellan. McCollam sent his remaining two boats to the Shumagin Islands, where the fish were abundant, and he then set about establishing a permanent fishing station on the islands. In 1876, he purchased a hunting camp, complete with several buildings and a wharf, at Pirate Cove, a picturesque and well-sheltered harbor at the north end of Popof Island, and converted the camp into Alaska’s first codfish shore station.

Originally manned by a company agent and about eight fishermen, Pirate Cove would gradually become the largest and most important codfish station in Alaska. Fishermen lived at the station and handlined for cod from dories (one man to a boat) in nearby waters, leaving the station very early in the morning and returning early in the afternoon to dress and salt their catch. Periodically a transporter from San Francisco would bring salt and other supplies and carry away a cargo of salted fish.

Back in San Francisco, McCollam searched for a place to cure his fish. He first started doing so north of the city, in Sausalito, but then moved his operation to a site near the mouth of Redwood City Creek, about 30 miles south of San Francisco, where he constructed wharves, storehouses, and flake (curing) yards. The flake yards were covered with lattice-like outdoor drying racks—known in the trade as flakes or flakeboards—that were used to dry fish during sunny weather. By 1876, McCollam had moved his operation to Belvedere Island, on Richardson Bay, about five miles north of San Francisco. The facility, called Pescada Landing, included wharves, fish houses, and nearly 14,000 square feet of flake yards. The main building was two stories high, with tanks that each held 12 tons of fish on the ground floor. In the 1880s and ’90s, McCollam merged with other companies, and together they formed the Union Fish Company in 1898.

Union Fish Co.’s codfish station in Pirate Cove, Popof Island, Alaska, dated May 1913. Courtesy of John N. Cobb photographs, University of Washington Collections.

But survival in the cod business required more than just Yankee savvy; it also demanded the ability to survive booms and busts. Production codfish in Alaska in the 19th century peaked in 1883 with a catch of 1,720,000 fish, followed by a period of reduced production that lasted almost two decades. Codfish fever, at that point, had run its course. In 1892, J. W. Collins, head of the U.S. Fish Commission’s Division of Fisheries, wrote its epitaph:

[F]or some years, the season of exceptional success was often the cause of disaster. Large profits generally created a temporary ‘boom.’ Firms or individuals hastened to engage in the fishery … Too often the products could scarcely be sold at any price because of the excess of supply over demand. The result was necessarily disastrous, and those who had hastened to engage in an enterprise because others had been “lucky” usually abandoned it with the utmost precipitation, leaving the field only to those whose “luck” or experience enabled them to succeed under conditions that ruined or discouraged their competitors.

Collins attributed the decline to market conditions (exacerbated by the inconsistent quality of salted codfish produced on the Pacific Coast), keen competition from East Coast producers, and the “tendency for capital to seek investment of the more promising salmon fisheries of Alaska.” And there was no lack of codfish. Collins wrote that the fishing grounds were “believed capable of furnishing an unlimited amount of cod.” This statement was clearly an exaggeration, but cod were definitely available in more-than-sufficient quantities to supply the California market.

Codfish fever may have faded, but the traditional Alaska salted-codfish industry persisted—and for some years thrived—after the fever was long-forgotten. In 1950, the Puget Sound-based Pacific Coast Codfish Company’s wooden sailing schooner C. A. Thayer made its final cod-fishing trip to Alaska, ending what some people refer to as Alaska’s salt-cod era. By that time, refrigerators had become common in American homes, and fresh and frozen cod had largely displaced the salted product.

The National Park Service restored the C. A. Thayer in the early aughts, and it is now moored at the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park.

Send A Letter To the Editors