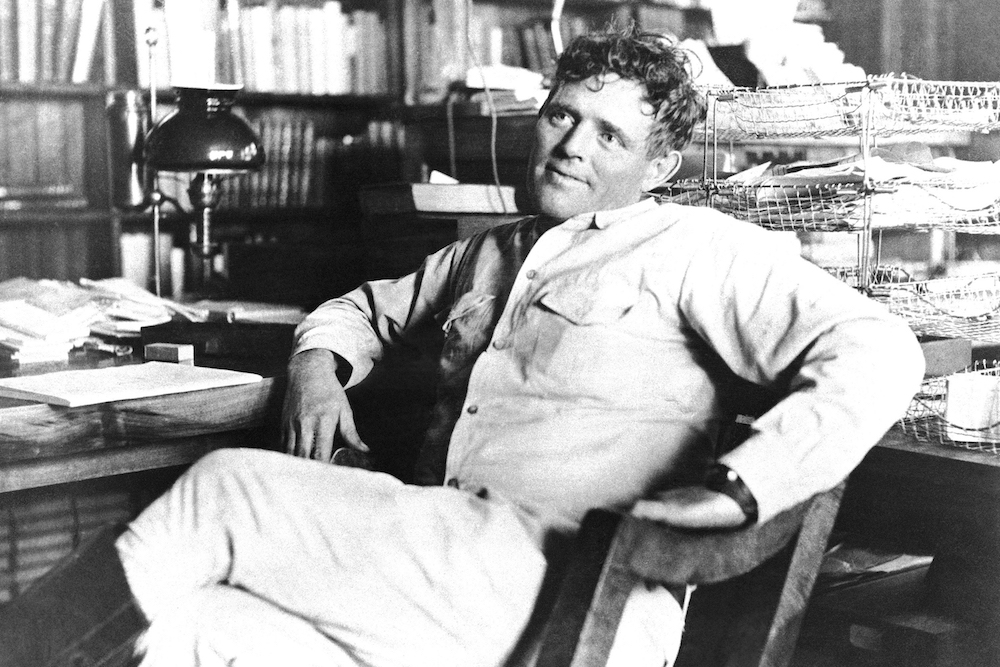

Jack London in 1916, shortly before his death. Courtesy of the Asociated Press.

Jack London saw this coming. So why didn’t we?

In 1910 the California author, already famous for The Call of the Wild and White Fang, wrote a short post-apocalyptic novel about a 21st-century pandemic in his home state.

To revisit The Scarlet Plague now, in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis, is to marvel at how much London understood—a century ago—about the challenges facing Californians now.

London imagined a global epidemic in the year 2013 that killed almost all the people in California, and presumably on Earth. In the novel, this “scarlet plague”—its victims became red-faced before dying—is recalled 60 years later, in the year 2073, by the only living pandemic survivor: a one-time UC Berkeley professor of English literature.

Jack London died in 1916, well before the medical advances that protect us against many diseases. And, having lived through a turn-of-the-century bubonic plague outbreak in San Francisco, he was more familiar with epidemics than we are. The Scarlet Plague thus expertly explains aspects of human behavior with which we have only become reacquainted during the current pandemic—from the enormous value of isolating yourself, to the mass madness at grocery stores, to all the myriad ways, both beautiful and awful, that people behave at moments like this.

But London’s larger message was even more powerful and prescient: When pandemic strikes, don’t be distracted by saving your home or your work or even your economy. Prioritize safety, and saving as many humans—and as much human knowledge—as possible.

London was from the Bay Area, and his plague novel is set firmly in Northern California. We start in 2073, with the elderly professor dodging bears. When he’s handed a 2012 coin found among the herds of goats that are San Jose’s only occupants, the professor tries to explain life before the 2013 plague to his grandchildren, who, like other humans of their time, are illiterate and savage hunter-gatherers. Education died with the 2013 pandemic.

London’s vision of early 21st century life wasn’t really too far off. He foresaw our wireless communications, the growth and wealth of the Bay Area, and the fact that America would be run by billionaires. In London’s story, the president of the United States is appointed by “the Board of Magnates,” a dozen rich men who fund and rule everything. The Bay Area of London’s imagining is full of restaurants and culture.

But in the summer of 2013, the scarlet plague hits, and all the modern institutions quickly stop. Then our basic systems of modern life are undermined by disease and death, and the fear that ensues. “The fleeting systems lapse like foam,” the professor says of the time. “That’s it—foam, and fleeting. All man’s toil upon the planet was just so much foam.”

London hits awfully close to our present predicament. For all the 21st century’s medical advances, London’s imaginary scientists can’t understand the micro-organism causing the plague fast enough. In the novel, there is too much confidence in the ability of modern society to find a cure. “It looked serious, but we in California, like everywhere else, were not alarmed,” the professor recalls. “We were sure that the bacteriologists would find a way to overcome this new germ, just as they had overcome other germs in the past.”

This fictional disease, like COVID-19, was transmitted easily by those without symptoms. During a lecture, the professor watches one of his students turn scarlet and die. Universities and schools were among the very first things to close. Before long, all enterprises have shut down, as people struggled to process the reality around them.

“Everything had stopped,” the professor recalls. “it was like the end of the world to me—my world … It was like seeing the sacred flame die down on some thrice-sacred altar. I was shocked, unutterably shocked.”

And London had a clear bead on what would happen at grocery stores during a modern pandemic, too. When hordes descend and begin stealing from a local store, the owner, unable to stop them, starts shooting customers. “Civilization was crumbling, and it was each for himself,” the professor recounts. With the fever spreading in the densely populated Bay Area, those with means try to escape the region. But they just end up spreading the plague to rural areas.

The professor struggles to remain composed as he sees people behave generously and heroically, but then die, even while the selfish live. “He was a violent, unjust man,” says the professor of one man who is spared. “Why the plague germs spared him I can never understand. It would seem, in spite of our old metaphysical notions about absolute justice, that there is no justice in the universe.”

The professor isn’t sure why he survived. Perhaps he is immune. But he also takes his brother’s advice to isolate himself. “To all of this I agreed,” the professor recalls, “staying in my house and for the first time in my life attempting to cook. And the plague did not come out on me.”

With nearly everyone dead, the professor finds a pony and makes his way east, eating fruit still hanging unpicked on trees and dodging packs of dogs that survive by devouring corpses. He crosses the Livermore Valley, and then forages through the San Joaquin, where he finds a horse that he rides up into Yosemite Valley. For three years, he makes “the great hotel” there his home, until the loneliness gets to him. “Like the dog, I was a social animal and I needed my kind,” he says.

So he rides back to Bay Area, where he discovers a few other survivors, who are living in different camps. The professor ultimately joins one such camp in Sonoma.

Society is not reconstituted. Sixty years after the Scarlet Plague, California is a lightly populated place of tiny tribes. There are the Sacramen-tos, the Palo-Altos, the Carmel-itos, and the professor’s own Santa Rosans, who are based in Glen Ellen (where Jack London had a ranch, now a state park). The professor also hears stories about Los Ange-litos. “They have a good country down there, but it is too warm,” he says.

The professor never reconciles himself to the post-pandemic reality. “The great world which I knew in my boyhood and early manhood is gone. It has ceased to be,” he says. “We, who mastered the planet—its earth, and sea, and sky—and who were as very gods, now live in primitive savagery along the water courses of this California country.”

The novel concludes with the professor telling his grandchildren that he has stored all his books in a cave on Telegraph Hill, hoping that the knowledge will survive him. He predicts that a new civilization will eventually rise, but it too will fail, because nature in the end always wins.

“All things pass,” the professor says.

London was famous for his faith in animals and his skepticism of people and the societies they construct. By my lights, the book underestimates the resilience of 21st-century institutions, and the goodness and determination of our fellow humans.

But this old little novel retains considerable power as a warning about the vulnerability of our state and civilization. Even advanced societies can fall apart quickly. Writing from the past, London reminds us that today’s horrors were not really unthinkable, and that, as we seek shelter now, we must not lose sight of the future.

Send A Letter To the Editors