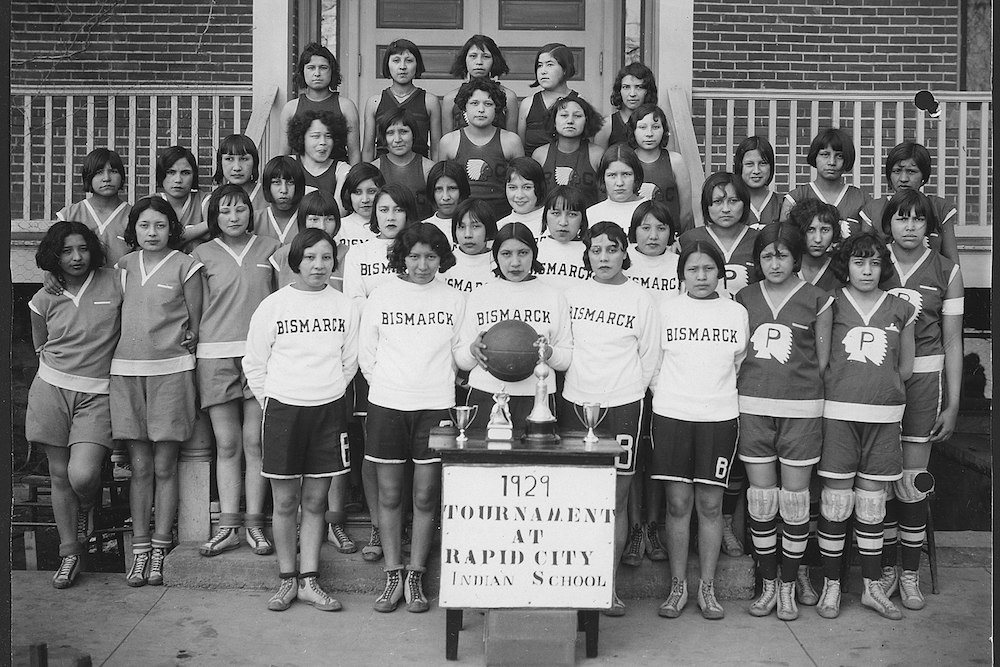

Four girls teams in Tri-State Indian School basketball tournament. Rapid City Indian School, 1929. Courtesy of the Department of the Interior, Office of Indian Affairs.

Nowhere today are people more passionate about basketball than in Native American communities. Why?

The hoops seen outside most homes and gathering places on western reservations speak to basketball’s cultural significance for Native peoples. For them, the sport is more than a pastime. It has become a modern expression of indigenous identity and pride, and a glue that bonds families and tribes more tightly together.

It might seem peculiar that a sport invented by Dr. James Naismith, a white man, has become so dear to Native people, especially since their ancestors first encountered it during hard times, in hard places. Native youths began learning basketball just prior to the turn of the 20th century while confined to government and missionary-operated boarding schools—or “Indian schools” as they were known. These institutions aimed to erase Native identities, and left many youths traumatized. Yet from these schools sprung a renewed athletic zeal that helped invigorate Native communities in times of struggle. The story of how this occurred speaks to both Native resiliency and the redemptive power of this sport.

Basketball’s association with the boarding schools’ assimilationist mission was more than incidental. In accordance with federal Indian policy, non-Natives in charge of these places used basketball, and other mainstream sports like football and baseball, as tools to mold Native boys and girls into model pupils, and model Americans. The idea was that playing exhilarating, well-ordered sports against white opponents would boost student morale, instill discipline, and improve race relations.

Native athletes largely rejected this agenda. They instead claimed possession of the sport to serve their own purposes. Ever-determined and adaptable, young Natives perceived structural parallels between basketball and their ancestral sports, and so played this new game to connect to the old ways and score victories amidst the injustices of the white man’s world. At the same time, the sport also allowed for escape. For youngsters who had been wrested from their homes and confined within institutional walls, basketball became a mental and physical refuge, allowing them to temporarily leave behind daily drudgeries, relieve stress, and bond with teammates.

Students could relate positively to basketball, despite its institutional attachments, because they exercised a surprising degree of control over their experiences with it during the early 1900s. Although authoritarian environments in most respects, the boarding schools were uncharacteristically lax in supervising athletics, due to understaffing. Outside of structured physical education classes, Native athletes self-managed most of their interactions with basketball. They formed and coached their own intramural squads, organized pickup games, and practiced shooting during precious moments of free time. Even in varsity contexts, Native captains directed on-court play, often under the supervision of Native coaches who were themselves graduates of these schools.

Students tasted similar freedoms playing other Indian school sports, but in fewer numbers. Compared to all-male football, which was the schools’ leading spectator sport, basketball’s availability to girls, as well as boys of small stature, made it a more democratic game. Its playability in tight spaces, minimal equipment demands, and easily learned rules further boosted its appeal, making it the most widely played Indian school sport by the 1920s, at both the intramural and varsity levels.

Basketball’s rise to popularity in the Indian schools was an underdog success story. Most administrators regarded the game as a minor diversion—especially compared to football, baseball, and track—when it debuted at their institutions. The supervising U.S. Indian Office only loosely promoted the sport, and local superintendents only occasionally introduced it. More often, lower-level employees and contract staff, many of whom had learned basketball through the YMCA (the sport’s parent organization), brought the sport to Native kids.

Despite humble beginnings, basketball caught on like wildfire amongst students within weeks after its introduction to various Indian schools during the mid-1890s and early 1900s. One hoops hot spot was Haskell Institute in Lawrence, Kansas, the second-largest Indian school after Carlisle, in Pennsylvania. By 1900, even before the school had purchased its first basketballs, students were shooting old footballs and clumped balls of rags at makeshift hoops all over campus.

We know this from their enthusiastic letters to relatives back home. “Basket ball is all we know now,” reported one female student. “In the girl’s building we play in the halls sometimes, with a bucket for a goal.” There was “not much to think about in what extra time we have except basket ball,” wrote one of the boys. In his letter, he included a written rundown of the rules so his parents could try it themselves.

Gymnasiums at Haskell and other Indian schools soon filled with boys and girls trying out for prized positions on newly organized varsity teams. Those talented enough to make these squads earned the pleasure of escaping campus for days or weeks at a time to compete on the road and see the country. The most athletically talented boys relied on basketball to stay out during lulls between football and baseball seasons, while it was the sole sport affording girls such opportunities.

Hawk Street in Starr School, Montana, on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation. Courtesy of Tony Webster/flickr.

Indian school athletes so embraced basketball, and intensively played it, that they developed their own stylistic approach by the early 1900s. In contrast to the plodding, controlled game many non-Natives employed, Indian school teams typically played an agile, fast-paced, high endurance, and long-shooting version that dazzled spectators and flummoxed opponents. As culturally diverse as these students were, most were from tribal communities that had long emphasized distance running as a life necessity—and as a spiritual bridge to immortal creators who had run their own races before the dawn of time. Prior to entering the schools, many tribal athletes had also played indigenous field sports like lacrosse that privileged agility, toughness, and speed.

While confined together, these youths developed an uncanny synergy that allowed them to channel these shared traditions into a new format. They did the same with football to a degree, as exemplified by Carlisle’s famously quick and nimble gridiron teams of the era, but basketball’s freer flowing design made it particularly conducive to stylistic innovation. It afforded the interpretive space they required to fully express the old ways through the new.

Indian school teams refined this swift, free-wheeling style so effectively that even the sport’s inventor took note. During James Naismith’s years coaching at the University of Kansas between 1898 and 1907, he frequently observed male players in action at neighboring Haskell Institute. “I made it a point to see several games at Haskell,” he later wrote, “because I delight in the agility of the Indian boys.” He was struck by how fast and effortlessly these athletes moved their bodies and the ball about the court, a style that matched his idealized vision of the game. Naismith did not comment on girls’ teams at the Indian schools, but sports reporters noted that they too were fleet of foot. Among them was a team of Yuchi girls in Oklahoma that outpaced its opponents while playing in moccasins. They were the only Indian school team in the country to opt for this footwear, no doubt because it increased their speed advantage over opponents who, in that era, commonly played in heeled leather shoes.

This high energy play made champions of some early Indian school teams. Haskell’s young men triumphed first, in 1902, when they snatched a national amateur title away from a team representing a fraternal order in Independence, Missouri. Soon thereafter, some Indian school girls’ teams captured state championships against high school and college opponents. Albuquerque Indian School took New Mexico’s territorial crown in 1902. The next year, Chemawa won in Oregon, and Fort Shaw triumphed in Montana. In 1904, Fort Shaw’s team earned even greater distinction while playing match games at the St. Louis World’s Fair. Led by sharp-shooting center Nettie Werth and forward Emma Sansaver, who was said to dodge “here and there with the rapidity of a streak of lightning,” they beat all comers and were dubbed world champions by some reporters.

News of what these teams accomplished instilled pride in tribal communities, thus spreading basketball’s appeal beyond the Indian schools. But regardless of whether they returned home as champions, thousands of former Indian schoolers all did their parts to disseminate the sport. By the 1910s and 1920s, hundreds were returning to the reservations each year committed to stay in the game and teach it to their tribespeople. They were soon joined by former schoolmates who had kept playing basketball in other formats prior to returning home. A handful beat long odds to play college ball, while hundreds more played in Army training camps during World War I, again relying on basketball to nourish their spirits during difficult times.

Dozens more made a go as professional barnstormers, capitalizing on the hoops skills they developed in the Indian schools to tour the country and earn a modest living. Notable among them was the world’s greatest athlete, Jim Thorpe. Although best known for his achievements in football, baseball, and track, he had also played basketball in the boarding schools. He returned to the game late in his professional sports career by captaining the so-named World Famous Indians from 1926 to 1928. Like other Native barnstormers, Thorpe and his teammates stayed true to the Indian school playing style, employing a fast “driving attack” that wore their opponents ragged, and drew enthusiastic crowds throughout the Midwest.

Sadly, public memories faded over time of what the Indian school teams and alumni had done to inspire tribal communities, and to inject added life into the sport of basketball. By the late 20th century, the Indian boarding schools had largely been supplanted by public high schools as the focal points for hoops ins Native communities. Only a handful of people remembered how the Native athletes at places like Haskell and Fort Shaw had claimed this sport for their people. But the legacy of those Indian school players nevertheless lived on—in the joys basketball kept bringing new generations of lightning-quick Native hoopsters and their adoring fans.

Send A Letter To the Editors