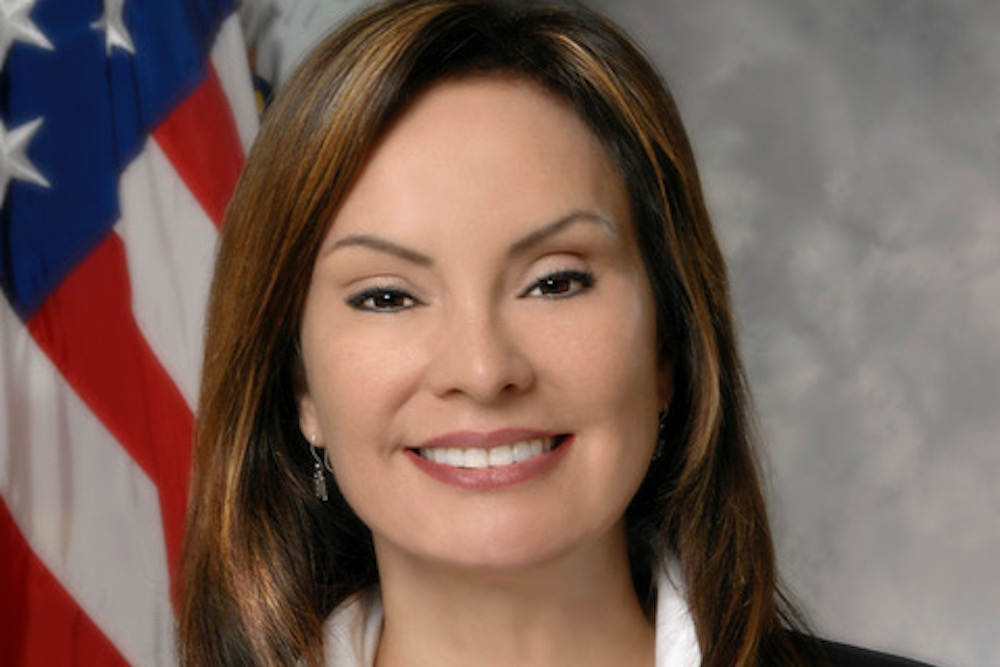

Rosa “Rosie” Rios is the founder and CEO of Empowerment 2020. She was previously the 43rd Treasurer of the United States, where she initiated and led efforts to place a woman on U.S. currency for the first time in more than a century. Before taking part in “Why Don’t Women’s Votes Put More Women in Power?,” the second event in the When Women Vote series presented by Zócalo and the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Rios stopped by the virtual green room to talk about her favorite teacher, being a “library fiend,” and why millennials and post-millennials make her hopeful.

How would you describe yourself in five words?

Constructive disruptor. Strategic. Forgiving. Empathetic.

Your educational project Teachers Righting History highlights historic American women in the classroom. Is there a teacher or professor who changed your life?

Mr. Wilder. He was my high school American history teacher. I keep in touch with many of my teachers. My third grade teacher just passed away last year, and I went to her funeral. But Mr. Wilder was definitely one of my favorites when I went to Moreau Catholic High School in Hayward, California. We reconnected because in the summer of 2015, when we announced that we were soliciting feedback from the American public for the redesign of U.S. currency. And I remember getting an email from Mr. Wilder. He wanted to congratulate me, but he also wanted to thank me. It was the first day of school, and he’d walked into the classroom, and after 34 years of teaching American history, he realized that he’d never had an image of a historical American woman on his classroom wall. He said he wanted to change that, and he did. He invited me back that fall, I walked into the classroom, and there on the walls were Susan B. Anthony, Harriet Tubman, and me. It was so touching. But I realized at that moment if one teacher or 10 teachers or a thousand teachers did the same thing, imagine what that would do to our girls and our boys.

I read that your first job was at the headquarters of the Alameda County Public Library. How have libraries influenced you?

I’m a library fiend. I was raised one of nine children by a single mother in not the best neighborhood, and so books were my window to the world. I relied on the libraries in my schools, the public libraries in my neighborhood. We all worked in my family, very, very young, and the way many of us started was through the Summer Youth Employment Program. When I saw that opportunity to work at the headquarters of the county library, I thought I had won the lottery. When you think about it, all the books that would come through the entire system would come through that area, so I basically had access to any book I wanted. I could borrow it and bring it back—usually, I read these books in a couple of days, one day if I could. I just loved it. To have that window to the world so early in life, there’s no doubt in my mind that that job was a huge part of how I got into Harvard.

Was there particular book that stood out at the time?

Shakespeare was really big for me. Especially my junior year, that was another teacher—Mr. Showers—my Shakespeare teacher. I couldn’t get enough. I just loved that it was such a different type of English. Such a different type of language. We grew up in a bilingual household, but to have that variation on English, if you will, and trying to figure out the nuance, the meanings, the comedy of Shakespeare was so entertaining.

What superpower would you like to have, and why?

I think I have it: The superpower of seeing the invisible. When I was part of the Treasury-Federal Reserve team in 2008, it was a very stressful time. I would take my breaks in the Treasury archive and look at all the financial products that the Treasury made. It wasn’t just currency—everything from savings bonds to the security page of your passport. All these products have all these renderings and artwork and concepts that were so gorgeous. And that’s when I noticed this pattern that there were no real women on them—they were allegorical, like Lady Liberty or women in togas. But every man that I came across was a real man, a Founding Father, a president, a cabinet member. I thought it was strange: This is the way we’re representing our history, and we’re missing half our population.

At the time that I realized that we’d never had a portrait of a woman on a Federal Reserve Note in the history of our country. We are the leader of the free world yet at that time, there were almost 30 countries who had women on their modern-day currency—and of the developed nations, it’s pretty much just us and Saudi Arabia. That is not something you want to have in common with Saudi Arabia. So to be able to see what’s missing for me has translated into all these other initiatives that I’m taking on, whether it is Teachers Righting History or my Notable Women project with Google, or my statue initiative. I have a trading cards initiative. I have a piece of legislation for women on coins.

So, that is my superpower. I see what is missing especially when it comes to women, women in our past, women in our present, women in our future.

Speaking of the future, you’ve called yourself a millennial/post-millennial advocate. What is it about that generation that gives you hope?

First of all, I have two of them. My son is 24, my daughter is 20. But when I started my work as a visiting scholar at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University in 2016, that was the year I launched Empowerment 2020, which is my initiative to physically highlight historical American women, but also advocate for women in positions of money and power. My audiences, when I had these focus groups, these town halls, I had a lot of young men. I talked about women flatlining at 20 percent in most every political and economic indicator. They didn’t understand; why is that the case? I realized, for the most part, these generations don’t judge by gender. That’s not the first thing that comes to mind. So when I started digging in and understanding them a little bit more, I realized my initiatives weren’t really gender initiatives; they were future leadership initiatives. This is about the future of the next generation and empowering them and hopefully seeing the world through their lens and seeing people as people and not boxes and checks.

My son, one of his essays for his Harvard application, he called it a “Tale of Two Grandmas.” He starts out by saying “I am Joey.” And he goes on and talks about his two grandmas, one from Hokkaido, Japan, and one Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico, and he explains how they both raised him with common values, and he ended the essay with “I am Joey.” And his point was that he’s not one or the other, and he doesn’t want to be defined by one or the other. It’s not just what you see; it is that third dimension of experiences and influences and feelings that we never really understand.