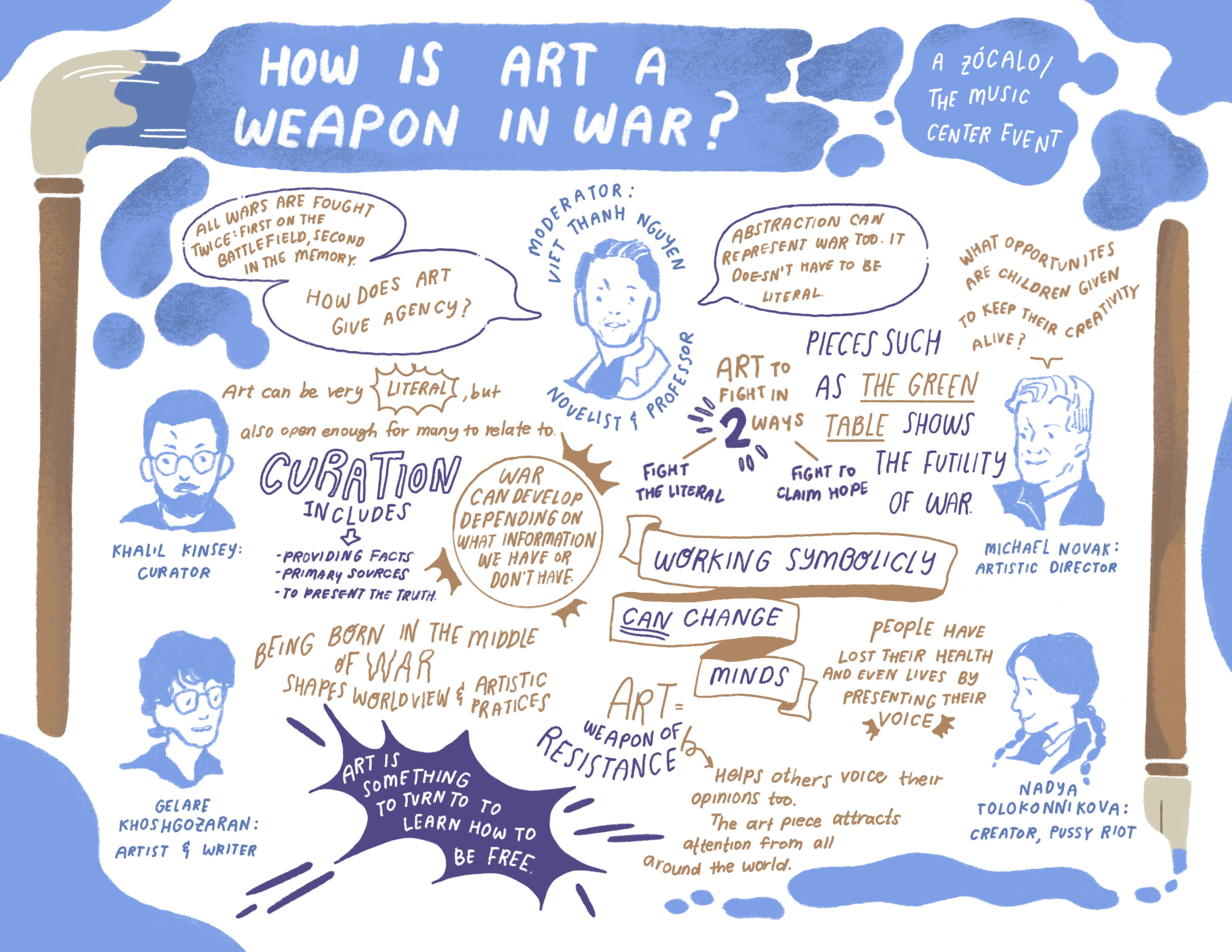

From left to right: Viet Thanh Nguyen, Gelare Khoshgozaran, Khalil Kinsey, Michael Novak, and Nadya Tolokonnikova.

How do you mobilize art against war? Can artwork be co-opted by warmongers? And what, if anything, can we hope for in creating and consuming art about war?

These were some of the many questions that guided last night’s Zócalo/The Music Center conversation, “How Is Art A Weapon in War?,” presented at Jerry Moss Plaza in downtown Los Angeles.

Maneuvering their personal and people’s histories and critiques of inhumane violence, the panelists helped us understand a major takeaway: Art at the intersection of war can help us understand the enigma that is our humanity—the worst, and the better.

Pulitzer Prize-winning author and USC professor Viet Thanh Nguyen moderated the event. He began the conversation by asking each panelist to speak about their relationship to art and war, to allow for their individual practices to give way to the bigger questions at hand.

Michael Novak, artistic director of the Paul Taylor Dance Company, spoke about The Green Table, Kurt Jooss’ interwar ballet, which will have a run later this week at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. The ballet, he said, depicts a group of men gathered around a green table who decide to go to war, and what to do in its aftermath. While it doesn’t give a resolution, it presents “the futility of war as a never-ending cycle.” In that way, he said, it’s timeless.

Nguyen agreed: “We’re still in a situation with mostly men around tables deciding what happens next.”

He turned to Iranian-born artist and filmmaker Gelare Khoshgozaran. Because she was born “in the middle” of the Iran-Iraq War, war shaped her worldview and artistic practices, down to her very notion of temporality. “It made me aware of time,” Khoshgozaran said. “The experience of time under the conditions of violence … and how banal—how normalized—it can get. You can’t just press pause because there’s a war.” In this way, peacetime never came for Khoshgozaran—war became not an event that has a beginning and end, but something with effects that resonate forever.

Khalil Kinsey, COO and chief curator for the Kinsey African American Art & History Collection, also spoke about the ceaselessness of war, the American Civil War—all that preceded it and succeeds it—and racial violence.

It is through his work at the Kinsey Collection that Khalil sees art’s power to engage in war. In a time when books are being banned and entire school systems are erasing important histories (all elements of a war on knowledge, Kinsey noted), providing historical truth and countering misinformation is its own form of resistance. “My curation is rooted into tapping into a consciousness,” he said.

The final panelist, Pussy Riot’s Nadya Tolokonnikova, was sentenced to prison because of her art. In 2012, she and other members of the feminist art collective were imprisoned for performing an anti-Putin song. “Did you anticipate that political repression and prison would be a consequence of your work?” Nguyen asked her.

Activists in Russia know they face consequences such as being poisoned, imprisoned, or murdered, said Tolokonnikova. “Our regime is based on the rule of thugs; they don’t have any grace or honor.” But she believes that protest is the only way to change the course of history. “Even if Putin dies tomorrow, if there is not strong enough resistance, it’s going to start over with another asshole.” This work, she continued, “is not fun—it sucks—but it’s what you should do.”

What about some examples of artworks that have resisted war? Nguyen asked.

Tolokonnikova cited the famed antiwar painting “Guernica” by Pablo Picasso. “He was just one guy, but widely influential.” She also pulled from her own history. After Russia invaded Ukraine, Tolokonnikova helped raise over $7 million to support Ukraine by creating an NFT of the Ukrainian flag. “I just think it’s our best bet to work on the symbolic level and change people’s minds,” she said. “You can create a momentum. Even the people with tanks are going to move to your side.”

Nguyen turned to audience questions before the panel wrapped. One person wanted to know aside from art expression, what methods of lifestyle practices helped them cope with the injustices they can’t unsee? The panelists all answered in pragmatic, quotidian terms.

“I hug my dog a lot,” Khoshgozaran said. For Kinsey, it was “the golden rule”—treating people the way he wants to be treated. Novak got off social media. And Tolokonnikova said she takes Omega-3 pills with her morning coffee.

Throughout the night, the conversation oscillated between hope and cynicism. Can art really move the needle? “I do believe in the micro affecting the macro, a ripple turns into a wave,” Kinsey said. After all, he continued, the options are laid out in front of us: roll over and lay down or create. “What choice do we have?”

Send A Letter To the Editors