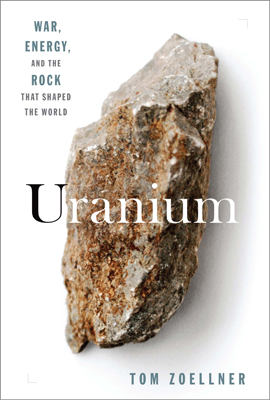

Uranium: War, Energy and the Rock That Shaped the World

by Tom Zoellner

In 1954, John Wayne and Susan Hayward filmed “The Conqueror,” a critically un-acclaimed film about Genghis Khan, in the town of St. George, Utah. “The canyon was breezy,” writes Tom Zoellner in Uranium, a history of that apocalyptic element, “and the cast and crew were constantly spitting dust from their mouths and wiping it from their eyes.”

The year before filming, shifting winds had pushed radioactive dust clouds into the region, all the way from atomic explosions in a desolate stretch of Nevada. Nevadans were proud that the badlands of their state were being put to patriotic, possibly progressive purpose. Zoellner notes that the Las Vegas High School class of 1951 made the mushroom cloud its mascot, and Clark County put the same image on its official seal.

But the more than 100 surface tests hit the region in just over a decade, Zoellner writes, sent residents to early deaths, possibly as many as 10,000 or more across five states. Wayne, Hayward, and almost half the cast and crew of “The Conqueror” died of various forms of cancer, a rate three times above average.

Zoellner’s Uranium tells how the element, which Zoellner describes memorably as the “geologic original sin,” has not only prematurely ended the lives of many Americans, including possibly the Duke himself, but has also shaped the last 70 years of science, politics, culture and economics. High-grade uranium was first found in 1915 in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo. The story of that spot, Shinkolobwe, opens the book and seems a foreshadowing of all that follows – in only a few pages it contains a quick history of the republic’s colonial period, the rise and fall of the fortunes of the uranium mine as political power shifted, the thrill of scientific discovery, the actual process of mining and smuggling uranium, and some religious storytelling. Shinkolobwe, which means thorny fruit, is said to be home to a malevolent spirit called Madame Kipese, who “needs to consume human souls to keep herself strong” and “emerges from time to time to kill someone.” It is because of her that Zoellner was discouraged from traveling to the mine.

The mysticism surrounding uranium makes for one of the book’s engrossing themes. It seems most every culture – secular American pop, rigorous scientific, Islamic and Australian Aboriginal, among others – regards the element with awe and dread. Certainly, much of Uranium is dedicated to demystifying uranium and the bomb. Zoellner explains, for instance, how exactly one inspects nuclear sites, how nuclear material is stolen and sold, how a bomb works, how a power plant works, how miners find it (particularly colorful characters there), and how the actual element sheds energy and transforms.

But Zoellner explores the spiritual aura of the element as well. Indigenous cultures seem aware of the toxic quality of certain sites where uranium is mined, and Zoellner retells the myths around them. Islamic countries, along with Israel and India, pursue the bomb with a messianic fervor. And the story of uranium itself, as Zoellner tells it, has enough strange coincidences to make a skeptic wonder. Most notable is how the U.S. received much of its uranium stockpile during and before World War II because of the actions of two foreigners – Edgar Sengier, who decided to put his Congolese uranium in a warehouse in Staten Island, and U-boat captain Johann Fehler, who surrendered Nazi uranium to the U.S. instead of to Britain, Russia, or France.

The mysteriousness of uranium comes from a basic and frightening place, according to Zoellner: the belief of almost all religions that “the world will end in fire.” Uranium gave believers and nonbelievers “a scientific reason to believe that civilization would end with a giant apocalyptic burning,” that the earth contained the means of its own destruction.

Of course, embedded in the earth, uranium is fairly harmless. And so Zoellner engages the fundamental question of whether to leave it in the ground – a particularly thorny debate in Australia, as he details – or whether we’re naturally compelled to pull it out, for reasons of economics, defense, or even evolution. His story ends on an ambivalent note, having covered the latest chapters of uranium’s story – the drama of Iran and North Korea and nuclear secret salesman A. Q. Khan, and the resurgent allure of nuclear energy – and leaving the distinct impression that the story will only grow stranger and more dramatic from here.

Excerpt: “In the first week of August 1945, for the very first time in history, that sliver of the mind that watches for the end of the world was handed a scientific reason to believe the present generation may actually have been the one fated to experience the last burning, and that all the cities and monuments and music and literature and progeny and every eon-surviving achievement and legacy of mankind could be wiped away from the surface of the planet as a breeze wipes away pollution, leaving behind only a dead cinder, a tombstone to turn mindlessly around the sun. Forty thousand years of civilization destroyed in twelve hours. For the religious and secular alike, uranium had become the mineral of apocalypse.”

Further Reading: The Heartless Stone: A Journey Through the World of Diamonds, Deceit, and Desire and Plutonium: A History of the World’s Most Dangerous Element

Send A Letter To the Editors