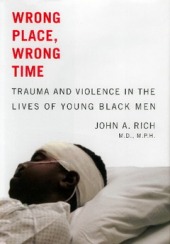

John A. Rich, a 2006 MacArthur Fellow and chair of the Department of Health Management and Policy at the Drexel University School of Public Health, catalogs in Wrong Place, Wrong Time: Trauma and Violence in the Lives of Young Black Men his quest to understand the cycle of violence in American cities. In the excerpt below, Rich, who visits Zócalo on March 5, explains what drove him to understand the often violent lives of young black men.

I will never forget the day in 1990 that I ran into my friend Dr. Jonathan Woodson in the stairwell at Boston City Hospital. Jonathan is a surgeon whom I first met when we were two of a handful of black residents training at the prestigious Massachusetts General Hospital. We both loved “The General” but, independently, we were both drawn to Boston City Hospital, a legendary public hospital famous for its care of poor patients and patients of color. We each chose to join the staff there – he as a trauma surgeon and I as a primary care doctor.

I will never forget the day in 1990 that I ran into my friend Dr. Jonathan Woodson in the stairwell at Boston City Hospital. Jonathan is a surgeon whom I first met when we were two of a handful of black residents training at the prestigious Massachusetts General Hospital. We both loved “The General” but, independently, we were both drawn to Boston City Hospital, a legendary public hospital famous for its care of poor patients and patients of color. We each chose to join the staff there – he as a trauma surgeon and I as a primary care doctor.

As usual, Jonathan wore a suit, tie, and a crisp white coat. He carried himself with the erect posture of the army reservist that he was. But this particular morning he looked unusually tired.

“We have to do something” he told me. “This violence is out of control. A couple of months ago, a young guy comes in with a bullet hole in his chest. We get him to the operating room in time. If that bullet had been two inches to the right, it would have gone straight through his heart. There are some tense moments, but we are able to do the repair. Save his life.

“Then this morning, I am driving to work and I hear his name on the radio. This same guy who we saved has been shot again. only this time he’s dead.” He shook his head. “We have to do something.”

Boston was in the midst of a bloody summer, and on many nights the emergency room brimmed with injured patients. Half of the beds on the surgical ward were filled with young men with gunshot or stab wounds. Nurses and social workers tried to care for each of them, but the pace was demoralizing. Even in the Young Men’s Health Clinic – the clinic I launched a year earlier to provide primary care to young men making the transition from pediatric care to adult care – patients who came in for routine physical exams lifted their shirts to reveal scars left by violence or by a surgeon’s attempt to repair it. most also concealed the deeper emotional scars left by trauma and abuse.

“What do you think we should do?” I asked him.

“I don’t know. Something. Anything. these guys sit up here in the hospital for days recovering. They literally do nothing! They just lie there in the bed. Somebody needs to talk to them.”

Young people were dying. Others were permanently crippled. Jonathan and I shared the deep frustration of treating these devastating injuries that were so preventable. As black men, each of us felt the pain of seeing our community’s potential lost, sometimes forever. These men were our reflection. We felt connected to them. but painfully, we felt powerless to do anything about it.

My encounter with Jonathan left me troubled. What he and I knew from our experience was confirmed by the available data. But the question remained: Why? Why were these young men getting shot and stabbed repeatedly? What could we say to them or do to them to keep this from happening?

As I struggled with these questions, I realized that, in the back of my mind, I held the implicit assumption that these young men had control over whether they got injured or not. Realizing that this belief sat unexamined in my head, I was disappointed in myself. Early in my career as a physician, I had learned that it was useless to blame people for what happens to them. We – doctors and nurses – are often wrong when we assume that we know why people do what they do in their often chaotic lives. But in this case, I realized that my assumption was the same one held by the police, my medical colleagues, and indeed, most of the people I knew. Simply put: young black men don’t just get shot, they get themselves shot.

The presumption that all injured young black men deserve what they get is simple but powerful. It summons up images of black ghetto gangsters warring over turf and drug trade. It suggests that these fallen young men are rarely innocent bystanders but rather willing soldiers in some vicious civil war in the urban jungle. This presumption is pervasive and seldom questioned. Doctors, nurses, EMTs, and social workers are not immune to the effects of this idea. Young black male patients are assumed to be guilty of something. But where did this stereotype come from? And more important, is it true?

My own experience as a physician did not support this image, and most of the young black patients I saw in the Young Men’s Health Clinic did not fit this stereotype. Kari, for example, had been injured when he tried to resist a robber’s attempt to steal his gold chain. Baron was stabbed in a fight with a former friend. David believed that he had been mistaken for someone else. Others told me that they had been stabbed over “something stupid” like an argument over money, a dispute with a girlfriend, or a threat to someone’s sense of “respect.”

There were some, a notable few, who admitted that they sold drugs or were “down with a gang.” Jimmy acknowledged that he was a “hell-raiser” in the Franklin Hill Housing Development, where he had grown up. He told me that the word in the street was that the masked man who shot him was a former partner in a gang who had a dispute or “beef” with him. Years ago, Mark used to sell drugs and carry a gun but had left all of that behind to make a new life for himself. But even though he grew up in the most violent streets in Boston, Mark did not cherish the chaos that came with the street life. When he did sell drugs, he did so “only until I get on my feet” or “until I can get a job.”

At the same time, the patients who came to the clinic brought the typical medical problems of late adolescence – acne, sexually transmitted diseases, teen fatherhood, and marijuana use – as well as the aftereffects of their injuries. Macho and guarded at first, this posturing melted away within the first few minutes of conversation. Their attitudes were not menacing or aggressive. Rather, they poured out their apprehensions, often while shedding tears, grateful for someone who would listen. Something did not fit. How could these be the same menacing criminals that the police targeted every day, that doctors dismissed as hoodlums?

It was against this backdrop that I felt compelled to hear what the young patients who filled the beds on the surgical wards had to say about violence from their own perspectives.

Excerpted by permission of Johns Hopkins University Press.

*Photo courtesy ~Steve Z~.

Send A Letter To the Editors